Eagles of the Third Reich: Men of the Luftwaffe in WWII (Stackpole Military History Series) (7 page)

Authors: Samuel W. Mitcham

Udet wrote his memoirs,

Mein Fliegerleben

, in 1934. In many ways it was very frank.

26

He tells, for example, how he froze in his first aerial combat and was almost shot down as a result. He soon managed to master his fear, however, and shot down his first airplane, a French Farman, on March 18, 1916.

After his first victory, Udet was assigned to the 15th Fighter Squadron. He did not score his second kill until October 12, and did not become an ace (i.e., did not register his fifth kill) until April 24, 1917. Meanwhile, he was commissioned second lieutenant of reserves on January 22, 1917. On August 5, 1917, Udet was named commander of the 37th Fighter Squadron. Here he came into his own. On February 18, 1918, he scored his twentieth victory when he shot down a Sopwith Camel near Zandvoorde. After that victory Capt. Manfred von Richthofen offered him command of the 11th Fighter Squadron, part of his famous 1st Fighter Wing. He led this unit for the rest of the war, scoring forty-two more victories and winning the

Pour le Merite

in the process.

27

When the Red Baron was killed in action on April 21, 1918, he was succeeded by Capt. Wilhelm Reinhardt, who was killed in a flying accident soon after. Most people expected Reinhardt to be replaced by Ernst Udet; everyone (including Udet) was surprised when Capt. Hermann Goering was given the prestigious command instead. Initially suspicious of Goering, Udet and he soon became fast friends.

After the armistice, Udet smashed his airplane and returned to Munich, where he worked for Gustav Otto as an automobile mechanic. On Sundays he worked for a POW relief organization by putting on exhibition dogfights against Ritter Robert von Greim, until Greim flew into a high-power line. The knight survived the crash, but his Fokker was a write-off and a replacement could no longer be obtained. Then Udet went to work as a pilot for the Rumpler Works, which had instituted air service between Vienna and Munich.

28

Udet was dissatisfied with civilian life in the Weimar Republic. When members of the Allied Control Commission confiscated his airplane, Udet worked in the construction of sports aircraft until 1925, when he moved to Buenos Aires as a stunt pilot and sports flyer. This was followed by a trip to East Africa, a barnstorming tour of the United States, and a hunting trip to the Arctic. He returned to Germany about the time Hitler came to power.

Nothing in Udet’s background or training qualified him for higher-level General Staff assignments. He also lacked the patience, maturity, toughness, and self-discipline necessary for such a post. He did not even want to join the Luftwaffe, but old comrade Goering insisted. He was inducted into the air force as colonel on special assignment on June 1, 1935. His promotion was rapid. He was successively named major general (April 20, 1937), lieutenant general (November 1, 1938), general of flyers (April 1, 1940), and colonel general (July 19, 1940).

29

Udet’s first major assignment came on February 10, 1936, when he succeeded his friend and stunt-flying partner, Ritter von Greim, as inspector of fighters and dive-bombers. Only four months later, on June 9, 1936, he succeeded Wimmer as chief of the Technical Office, which became the Office of Supply and Procurement in 1938. This bureau was responsible for aircraft and weapons development, procurement, and supply for the Luftwaffe. Udet converted it into a hopelessly bureaucratic organization, in which Udet himself tried to direct twenty-six separate departments in between wild parties, drunken sprees, drug abuse, and womanizing. Udet smoked to excess, drank far too much, periodically ate only meat, and took drugs—especially ones with depressing side effects. Department heads were not able to see their boss for weeks at a time, and critical decisions were made by default.

30

The entire office became a hotbed of in-fighting and political intrigue. As a result, Germany’s technological advantage in aviation stagnated and was eventually overtaken by the Allies. The “second generation” of German aircraft, including the Me-109 fighter, the He-111 bomber, and others, had been developed under the guidance of Milch and began coming off the assembly lines in 1936. The next generation of German aircraft never fully developed, due to Udet’s mismanagement. The Luftwaffe’s loss of the Battle of Britain in 1940 was a direct result of this technological failure, but more about this later.

The Luftwaffe was reorganized again in early 1939, causing even more harm to the air force. The High Command of the Luftwaffe (OKL), which was headed by the chief of the General Staff (Stumpff and, later, Jeschonnek), was separated from RLM, but not entirely. The chief of the General Staff was made solely responsible to Goering, although he had to inform Milch about operational matters. All departments of the General Staff not directly concerned with operations were to be absorbed by RLM. The chief lost control of communications and partial control of training. Two new organizations were created: the Office of Signal Communications (Maj. Gen. Wolfgang Martini) and the Office of Training (Lt. Gen. Bernard Kuehl), which controlled no fewer than fourteen inspectorates. The chief of personnel (Greim) was directly responsible to Goering for officer appointments, but in all other matters was subordinate to Milch. The Office of Air Defense was once again placed under the state secretary. In addition, Milch retained the post of inspector general of the Luftwaffe, which enabled him to inspect units in the field and meddle in the affairs of the General Staff. The Office of Supply and Procurement (Udet) remained independent of both the General Staff and Milch.

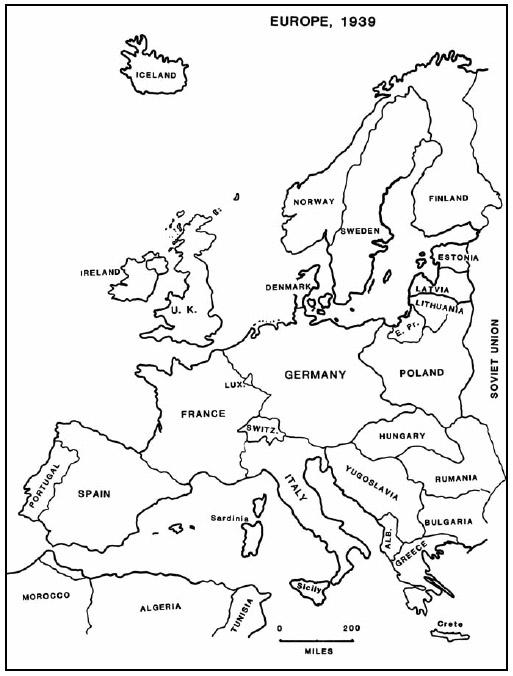

Map 1: Europe, 1939

Map 1: Europe, 1939

Hans-Juergen Stumpff was a stopgap appointment as chief of the General Staff. A congenial Pomeranian and a veteran General Staff officer, he was a good administrator but was unsuited for the post of chief, and he knew it. He had enjoyed being personnel director but did not like being in the middle of the battle of intrigue for control of the Luftwaffe. He tried to straighten out the organizational mess but failed. He was relieved when he was succeeded by Hans Jeschonnek, the former chief of operations of OKL. Stumpff took over the Office of Air Defense—ironically enough under Milch. Meanwhile, Jeschonnek became the fourth chief of the General Staff in four years.

Jeschonnek was born on April 9, 1899, in Hohensalza, East Prussia (now Inowroclaw, Poland), the son of an assistant secondary schoolmaster. His oldest brother, Paul, had been one of the rising stars of the secret aviation arm of the Reichswehr until he was killed in an air accident at Rechlin in 1929. Hans’ own youngest son, Gert, served in the German Navy in World War II and later held several important posts in the West German Navy.

At the age of fifteen and one-half, Hans Jeschonnek volunteered for service in World War I. He attended the elite cadet school at Gross-Lichter-felde, received his commission, underwent pilot training, and joined the 40th Fighter Squadron in 1917. He scored two aerial victories prior to the armistice. In 1919 he took part in the fighting against the Poles in Upper Silesia as a member of the 6th Cavalry Regiment. After this he joined the Reichsheer. In 1923 he was assigned to the Army Ordnance Department as a member of the staff of Capt. Kurt Student in the Inspectorate of Arms and Equipment, one of the camouflaged air branches of the Reichswehr. In this office he studied aircraft development in neighboring countries, including Sweden, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. After that he underwent clandestine General Staff training and graduated at the head of his class in 1928.

Lieutenant Jeschonnek was assigned to Inspectorate 1 of the Reichswehr Ministry in April, 1928. Actually he worked for Lt. Col. Hellmuth Felmy in the inspectorate for the clandestine air units. On January 30, 1933, he was named adjutant to his friend, Erhard Milch, the state secretary for the Reich Commissariat of Aviation. Next he did a tour of troop duty and was in the 152nd Bomber Wing in March 1934, when he was promoted to captain.

Hans Jeschonnek was an extremely bright young officer and a thorough professional who impressed all who came into contact with him with his military bearing. After 1934 he was promoted rapidly—in fact, far too rapidly. It had taken him seventeen years to advance from second lieutenant to captain. In the next eight years he would be promoted to colonel general—the second-highest rank in the service (excluding the rank of Reichsmarschall, which Hitler created for Hermann Goering in 1940 and which was held only by him). Jeschonnek was successively promoted to major (1935), lieutenant colonel (1937), colonel (1938), major general (1939), general of flyers (1940), and colonel general (1942). The grade of lieutenant general he skipped entirely.

Meanwhile, Jeschonnek made a deadly foe. Shortly after he assumed command of the III Training Group of Air Administrative Area I, which was stationed at Greifswald, Erhard Milch tried to have him court-martialled. Why the two fell out is not known. Once good friends, they were now bitter enemies. Jeschonnek, however, was protected by Kesselring, who virtually told Milch to mind his own business. As we have seen, there was no love lost between those two, either.

Jeschonnek was assigned to General Staff duties in 1937 and was named chief of the operations staff of the OKL in 1938. He became chief of the General Staff on February 1, 1939. His appointment came as a surprise to many. It is true that Wever looked upon him as a potential successor, but then Wever had not planned on dying so suddenly.

Did Hermann Goering appoint Jeschonnek to this post because of his known antipathy for Erhard Milch? We will never know for sure, but it was almost certainly a factor. Stumpff had tried to work with Milch, but it was certain Jeschonnek would not. Another factor was that Goering believed he could work more easily with young men than with older officers, many of whom were his seniors and who had definite views on matters of high command, were not prone to compromise, and felt they owed little or nothing to Hermann Goering. Goering felt threatened by strong-willed officers such as Kesselring, Greim, Richthofen, and, of course, General Milch.

Hans Jeschonnek’s position was difficult from the beginning. He found it hard to force his views on generals so senior to him in age, rank, and experience. He often felt it necessary to make concessions, especially when dealing with Kesselring, Sperrle, and Baron von Richthofen. Jeschonnek also lacked the gift of winning the cheerful and enthusiastic support of his subordinates, with whom he tended to be too reserved or sarcastic. “Despite his keen intellect,” Suchenwirth wrote, “Jeschonnek . . . lacked an understanding of human nature, the cardinal attribute of a leader.”

31

As if all of this were not enough, Jeschonnek also had difficulties in dealing with Goering’s “inner circle.” This group included Gen. Bruno Loerzer; Paul “Pilli” Koerner, the state secretary for the Four Year Plan; Gen. Karl Bodenschatz, the chief of the Ministerial Office and Goering’s liaison officer to Fuehrer Headquarters; Alfred Keller, the commander of Luftkreis IV; and Col. Bernd von Brauchitsch and Lt. Col. Werner Teske, Goering’s adjutants. None of these men liked either Milch or Jeschonnek, whom they looked upon as rivals for power. This group formed a sort of collateral High Command and was sarcastically referred to as the “Little General Staff.” Their power was very real, however, because Goering took their advice all too often. Frequently Goering would go to his hunting lodge in Rominten, or to Karinhall, or to his castle at Veldenstein in Upper Franconia, and would issue orders to the various commands through his adjutants, bypassing Jeschonnek completely. This situation frustrated and confused the young chief of the General Staff. And no wonder! It would be difficult to design a command arrangement more disunified and fragmented than that of the Luftwaffe. It was, in reality, virtually leaderless, and would remain so for the rest of its existence.