Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (39 page)

Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

After marriage, most Elizabethan and Jacobean aristocrats spent the bulk of their lives in the countryside. There, they managed their estates, oversaw the administration of justice, presided over important festivals and social events, and attended the local church. Some historians, aware of the networks of political, social, and family connection which centered on these families and estates, noting that contemporaries used the word “country” to mean their “county” or “locality,” have posited the existence of “county communities” whose leaders governed and socialized together, marrying their children to each other. In fact, as we shall see, the greatest noble and gentry families increasingly based their lives in London as well as their estates and, thus, often married and socialized across county lines. But most middling and lesser gentry did, indeed, tend to think and act as if their principal county of residence was the world, its center, their country house.

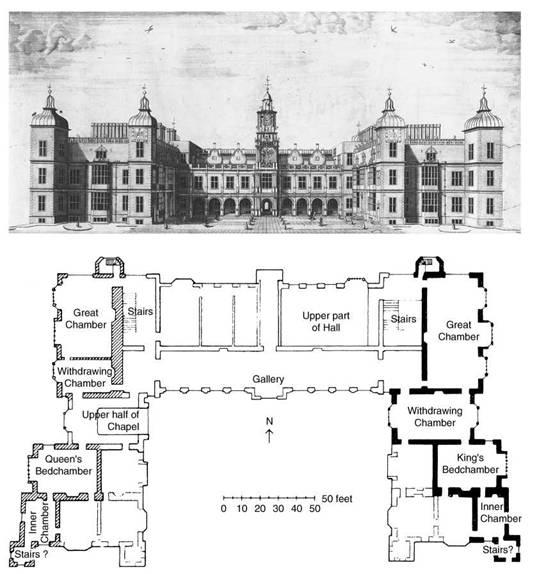

We wrote “country house,” not castle, because the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries were a great age for tearing down castles. This was largely due to the Tudor suppression of great noble affinities and the rise of siege artillery which could knock down medieval castle walls. Between 1575 and 1625, out-moded and drafty castles were being replaced by large, airy country houses with lots of windows, surrounded by extensive gardens and parks. The greatest of these, such as Sir John Thynne’s Longleat in Wiltshire or Sir Robert Cecil’s Hatfield in Hertfordshire, were known as prodigy houses (see

plate 9

). These mansions tended to reflect two contrasting goals of aristocratic life: the longstanding desire to project to the outside world an image of status, wealth, and power; and a new concern for privacy. Unlike medieval castles and houses with multiple enclosed courtyards, their ground plans were often in the shape of an E or an H (see diagram), with a hall in the center or on one wing for dining and ceremonial occasions, and private apartments on the other. The former would allow the family to entertain the county community; the latter would allow their daily lives to take place in private. The days when a great landowner took his meals in the great hall surrounded by servants and retainers were gone. Indeed, an important early modern architectural and social development was the rise of the “withdrawing room,” or, as it came to be called, the drawing room, to which the family could retreat from the prying gaze of guests, servants, and tenants. These two areas and their functions would be connected by a long gallery full of paintings of the family’s ancestors, a display of lineage to those privileged to be invited inside. For the rest of the world, there was the building’s magnificent, if not necessarily welcoming, façade behind high walls and impressive gates.

These houses thus provided both public and private space. The former allowed them to be great political and social centers. Here, the local aristocracy gathered to select MPs or plan the implementation – or thwarting – of some royal policy. Traditionally, great families were also supposed to provide hospitality at key times of the year, such as Christmas, inviting the whole community, down to its lowest ranks, into their houses for feasting and revelry. On summer progress, Queen Elizabeth often imposed upon the hospitality of her most prominent subjects by turning up at their estates with her entire courtly entourage. This mark of royal favor was highly prized, but it could also be ruinous: the earl of Leicester once spent £6,000 to entertain the queen and her court at Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire!

At least the man who paid the piper did not have to play the tune: that’s what servants were for. A great nobleman’s household might employ over 100, a middling gentleman’s, at least 20. During the sixteenth century a great peer employed gentlemen ushers to open doors, valets and ladies’ maids to assist his and his spouse’s daily toilet, chambermaids to clean his house, tutors to instruct his children, cooks for his kitchen, servers for his hall, footmen and grooms to perform menial tasks about his stables, and, of course, an army of grounds keepers, laborers,

Plate 9

Hatfield House, south prospect, by Thomas Sadler, 1700. The diagram shows the plan of the first floor. Reproduced by Courtesy of The Marquess of Salisbury.

and tenants to farm his estate. Supervising all of these would be a majordomoor steward, who was, himself, a gentleman of some education and ability. As the seventeenth century wore on, aristocrats would find less need for all this attendance and would reduce their domestic establishments accordingly.

Large establishments of servants freed the landed classes from manual labor. It could be argued that early modern society geared the activities of the vast majority of people toward providing pleasant and fulfilling lives for a very small minority who did not work and who were proud of never having to do so. This freedom from work (or, more accurately, from manual labor) and the gradual decline in emphasis on their military role role allowed the aristocracy to concentrate upon other things: their duties as government officials, MPs, lords lieutenant, JPs, or sheriffs; the round of hospitality noted above; the traditional amusements for men of hunting and hawking, for women of conversation, sewing and playing music; and the making of lawsuits and scholarship. Litigation, usually over land, was an increasingly popular form of aristocratic conflict, which, along with the highly ritualized challenge and duel, replaced the old-style blood-feud between families. As for scholarship, by 1550, illiteracy was virtually unknown among the elite. The Tudor and Jacobean periods saw both upper-class men and women, many educated in the humanist tradition, devote themselves to philosophy, history, poetry, and art. The English gentleman excelled particularly at the literary arts: Sir Thomas More wrote

Utopia

(1516) and a

History of Richard III

(first English edition 1543); Sir Thomas Wyatt (ca. 1503–42, father of the rebel of the same name) developed the English sonnet; Sir Philip Sidney (1554–86) wrote

Arcadia

(1593); Sir Walter Ralegh, a history of the world (1614); and Sir Francis Bacon, Viscount St. Alban (1561–1626), laid important ground for the development of the scientific method in his

Advancement of Learning

(1605) and

New Atlantis

(1626), and for letters in his

Essays

(1597 and 1625). These men combined private learning with public duty: More and Bacon were lord chancellors and Wyatt, Sidney, and Ralegh were courtier-soldiers.

One reason for all this cultural activity, as well as the above-noted decline in numbers of servants, was that nobles and great gentlemen increasingly forsook their country homes for the delights of London and the court. A small but growing minority rejected local society entirely, living at court as permanent employees of the government or the royal household – or hanging about in the hope of landing such employment. Others were amphibious: at home in both the provinces and the metropolis. By the Jacobean period there developed a London “season” from the late autumn to early spring, during which the landed aristocracy resided in the capital, attended plays, balls, and parties, and kept an eye on promising marriage prospects for their children. Several technological developments made this easier. In particular, the invention of the coach with box springs meant that an aristocrat could transport his entire family to the city in relative comfort. There was a concurrent improvement in road quality and, thus, safety – although a gentleman whose coach was overtaken by highwaymen or became mired in late spring mud would dispute this. For those who could not make it to the metropolis, from at least the mid-seventeenth century on an increasingly efficient postal service enabled them to receive news and stay connected via correspondence with those who were there.

The increasing resort of aristocrats to the metropolis and the court contributed to the gradual domestication and nationalization of the English landed elite. That is, by the end of the sixteenth century the English nobility and gentry had largely transformed from a feudal military cohort of limited local horizons and parochial ambitions into a service aristocracy whose primary responsibilities and interests were governmental, social, and cultural, whose loyalties were paid to the sovereign, and whose tastes were increasingly cosmopolitan. These changes, as much due to economic and social shifts as to the actions of the Tudors, would continue under the Stuarts, rendering the landed elite partners of the monarch instead of rivals – at least most of the time.

Commoners’ Private Life

How different were the private lives of those who served or rented from the landed elite, those who, traditionally, had “neither voice nor authority in the common wealth”?

11

As we have indicated, those differences appeared, first, in the nature of the household and family into which one was born. Those of the middling ranks (merchants, professionals) might include a mere handful of apprentices and servants. At the lower ranks, families tended to be even smaller, more self-contained and “nuclear.” There were many reasons for this. People of all ranks did not, in general, live long enough for there to be simultaneously living grandparents, parents, and children. At the lower ranks, this was exacerbated by the fact that, though marriage was the ideal, many people never tied the knot: possibly 20 percent of all Englishmen and women remained single for their entire lives and at any given time, over half of all men and women were living in a single state. Those ordinary men and women who did marry tended to do so much later than their superiors, in their mid-to-late twenties for men, their early-to-mid-twenties for women. They waited because of financial considerations: a non-elite male was expected to be able to support his wife and family. Even if their parents and grandparents were living, the common expectation was that they would set up separate households. It might take years of hard work to reach this point. Since menopause tended, during the early modern period, to come in a woman’s midthirties or early forties, this limited her childbearing years and so the number of her children. Breastfeeding, a common practice at this rank, probably had some contraceptive effect. Yet another, more tragic, limitation on family size came from very high rates of infant mortality at the end of the sixteenth century: one in eight children died within the first year of life and fully one-quarter of those born never reached age 10.

12

A final reason for small, nuclear families was that, as indicated above, people in the lower orders often had to move about in search of work, cutting contact with extended family. Take, for example, the limited chances for family formation in the life of one Thomas Spickernell, described with some disapproval by an Essex town clerk in 1594: “sometime apprentice to a bookbinder; after, a vagrant peddler; then, a ballad singer and seller; and now, a minister and alehouse-keeper in Maldon.”

13

Thus, for the great mass of the people, families might come in many forms, but were generally small, say four to five individuals. Death often broke them up, only to produce new combinations if surviving adults remarried.

Despite the high rate of infant mortality, the relatively short life expectancy of adults (about 38 years) must have meant that children formed a higher proportion of the general population (perhaps 40 percent) than they do in highly developed countries today. That is, children were everywhere. What was early modern childhood like at this level of society? A relative lack of evidence on this question, much of it subject to conflicting interpretations, has led to a vigorous academic debate. There were some contemporary guidebooks on child-rearing, but, like their modern equivalents, they may reflect more wishful thinking than actual practice. Surviving diaries and letters of ordinary people are sparse and often terse. In particular, parental reactions to the deaths of children were often, by twenty-first-century standards, short and unemotional. Thus, the preacher Ralph Josselin (1617–83) wrote of his infant son, Ralph, who died at 10 days old, that he “was the youngest, & our affections not so wonted unto it.”

14

This led historian Lawrence Stone to argue that, because the loss of a child was so common, parents may have reserved themselves emotionally from their children during the first few years of life. Stone and others, noting the formal and utilitarian nature of children’s dress, the relative lack of toys, and the tendency of children’s literature to emphasize moral instruction over entertainment during this period, have argued that early modern children were generally ignored, disciplined severely, or treated like miniature adults or pets. But other historians, such as Ralph Houlbrooke, Linda Pollock, and Keith Wrightson, have argued that few words may hide deep emotion.

15

In fact, there is a fair amount of evidence to support the marquess of Winchester’s contention that “the love of the mother is so strong, though the child be dead and laid in the grave, yet always she hath him quick in her heart.”

16