Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (45 page)

Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

Unlike the narrow world of the village, here you would encounter individuals from every part of England and many parts of Europe, with different accents and, perhaps, different religious and social traditions from yours. Your own customs would soon be left behind as irrelevant. Where, in the village, the sun and agricultural seasons (spring for planting, autumn for harvest) determined time, now your day ran according to your master’s watch; your job as a servant or a tradesman carried on irrespective of the season. Disease and sudden death would have been even more prevalent than in the village. This, plus changing economic opportunities, meant that your business relationships and friendships would be made and broken far more quickly, far more casually, and far more often than in the village. Membership in a livery company did provide a social network and safety net. But after peaking at three-quarters of London’s adult male population in 1550, guild membership declined. For those who did not join, London might be a very lonely place, especially for someone used to close, paternalistic village life. But if you had found the village community stifling, with its lack of privacy and enforcement of communal norms by your neighbors through rough music, skimmingtons, gossip, etc., you might revel in the economic opportunity, freedom, and anonymity to be found in the city.

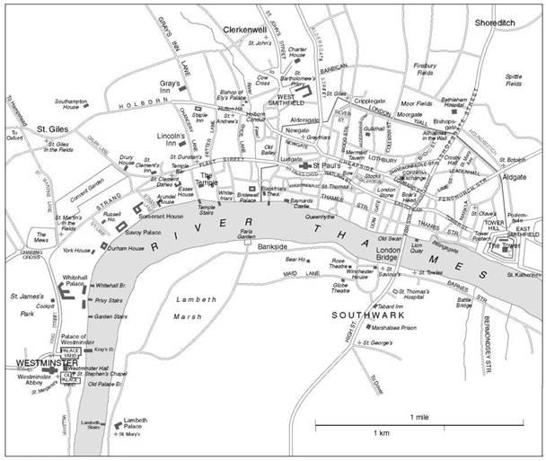

London was at once the capital, court, legal headquarters, chief port, and entertainment center for the entire country. In many ways, it was really two cities joined by a river (see

map 10

): the city of London proper (i.e., more or less within the walls, ruled by the lord mayor and court of aldermen); and the borough of Westminster (administered by 12 burgesses selected by the dean of Westminster Abbey). First, let us examine the river. The River Thames was the reason for London’s existence in the first place. As with the English Channel and the seas around the British Isles, the Thames was a highway, connecting the southern interior of England with the Channel, those seas, and the continent. London sat at a crossroads: the westernmost point on the river wide enough for big ships to dock; the easternmost point narrow enough for land traffic to cross. This made London an intersection between traffic north–south and east–west. London Bridge (see

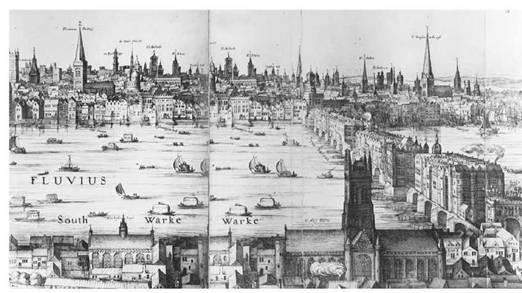

plate 11

) had linked the north and south banks of the Thames since the twelfth century. In fact, London mostly developed on its northern bank; to the south was the suburb of Southwark. Here, on the fringe of the city’s jurisdiction, flourished theaters such as the Rose and the Globe, bear-gardens (for bear- and bull-baiting), brothels, and taverns. In short, if you wanted an exciting – or a dangerous – time in London, you headed across the bridge.

But for most Londoners, the crucial connection was between London in the east and Westminster in the west, between city and court. Since the road connecting London to Westminster, known as the Strand, was still not entirely (or reliably) paved in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the river continued to be London’s chief east–west link via watermen and their barges, which operated as water-taxis for its inhabitants. It was also its chief source of wealth, for the river below London Bridge and to the east was full of docks, and ships, lighters, and barges waiting to use them. These brought immense profits into the oldest part of London, later known as “the City” (

map 10

). “The City” is modern shorthand for the financial district which still sits within the square mile once bounded by the old Roman city walls. Here, ca. 1603, might be found the Guildhall, London’s city hall, where its lord mayor and 25 aldermen met to govern the metropolis; numerous smaller halls which housed the livery companies associated with each trade; Cheapside, a broad street lined with shops; and the Royal Exchange, built by Sir Thomas Gresham (ca. 1518–79) in 1566–7, where merchants met to strike deals. The merchants who struck those deals helped make London England’s greatest center of wealth. The greatest merchants would serve as aldermen: of 140 aldermen serving under James I, over a third died worth £20,000 or more. Loans from the London corporation and merchant community were crucial to the government, especially during crises. That, combined with its prestigious civic government and its great population, made the city a vital ally or a dangerous enemy to any royal regime.

Map 10

London ca. 1600.

Plate 11

Visscher’s panorama of London, 1616 (detail). The British Library.

The city skyline was dominated by the spires of 96 parish churches and, towering over even them, old St. Paul’s Cathedral. The other landmark recognizable to all Londoners was the Tower of London, at once a former royal palace, a fortress that dominated the river approaches to the city, and a royal prison for high-ranking political prisoners. Here, the Tudors’ most prominent victims had met their ends. Apart from these great buildings, London within the walls was a maze of narrow medieval alleys and courts dominated by multi-story ramshackle wood and plaster buildings, their eaves projecting into the street. Many had been thrown up hurriedly to deal with the population explosion and were none too safe. These narrow lanes and rickety buildings, lacking modern sewer facilities or street lighting, bred crime, disease, and fire. They thus help to explain why London was such a dangerous place and, more particularly, why its death rate was so high.

Plate 12

A view of Westminster, by Hollar. Palace of Westminster Collection.

No wonder the royal family had long since abandoned the Tower and the city within the walls to move west, upriver and upwind, to the network of palaces around Westminster (

map 10

). Unlike neighboring London, Westminster was not an independent city with its own charter and government but an unincorporated part of Middlesex and the seat of royal government. At Westminster might be found a complex of buildings which formed the nation’s administrative heart (see

plate 12

). First, there was Westminster Abbey, where English monarchs were crowned and, prior to 1820, buried. Close by was Westminster Hall, originally a part of Westminster Palace but in 1603 the site of the courts of King’s Bench, Common Pleas, and Chancery. The law courts drew the elite to London, for the complications of land inheritance and purchase caused frequent litigation. Another such drawing card was Westminster Palace, located on the river, which was the home of the Houses of Parliament. This ancient structure was donated by Henry VIII to Parliament when he acquired Whitehall, just a few yards away, in 1529. The building was never adequate, either as a royal palace or the site of a legislature. It was to burn down in 1834 and be replaced by the present, far more splendid, Palace of Westminster.

But the most significant attraction to London for the upper classes was the court at Whitehall. This massive, disorganized series of riverside buildings, consisting of well over 1,000 rooms, had been built for Cardinal Wolsey as York Place. Henry VIII confiscated it, renamed it, expanded it, and made it the sovereign’s principal London residence in 1529. Henceforth, Whitehall was the place where the great offices of Tudor and early Stuart government, such as the Privy Council and Exchequer, met; indeed, to this day the word “Whitehall” is synonymous with government in Britain. Thus, this was where the monarch’s chief ministers and foreign ambassadors might be found and conversed with, privately if necessary. This was where the latest play or poem or fashion or invention often made its first appearance. Above all, this was where the sovereign, God’s lieutenant on earth, attended the council; appeared in the Presence Chamber; presided over elaborate balls, plays, masques, or State dinners; and might be approached, and begged for favor. Courtiers thronged Whitehall’s galleries hoping to be noticed for bravery or beauty or talent or wit. As in Hollywood today, most failed. Still, if one wished to rise in the world or found a great family in 1603, one went to court.

In order to be close to all of this opportunity, the aristocracy increasingly followed the court by moving west. As we have seen, many young gentlemen acquired a smattering of legal knowledge and social polish at the Inns of Court, four law schools (the Middle Temple, Inner Temple, Lincoln’s Inn, and Gray’s Inn) located just west of the walled city. Before the Reformation, wealthy bishops had built enormous palaces along the Strand between London proper and Westminster. After the confiscations of the mid-sixteenth century these palaces were awarded to great courtiers, many of whom renovated or rebuilt them. Thus, Protector Somerset built Somerset House and the earl of Essex, Essex House. The Russell family, earls of Bedford, had even bigger plans. They acquired a parcel of former Church land just west of the City and north of the Strand called Covent (i.e., Convent) Garden. In the 1630s they commissioned the architect Inigo Jones (1573–1652) to design accommodation for gentlemen who attended the royal court or the law courts. The result was the first London square, a form of civic design modeled on the open Italian piazzas and intended to provide airy yet private housing. During the seventeenth century, the ambitious aristocrats who flocked to court, along with rising merchants and professionals, would push even further westward, leading to the building of additional squares throughout what became known as the West End of London.

Trade, Exploration, and Colonization

London, like most cities, rose or fell on the profits from trade. At the end of the Middle Ages, international trade was dominated by great trading companies, the most famous of which was the Hanseatic League. The Hanseatic League was a union of merchants from Northern Germany who had been given trading privileges by certain countries, including England. Such leagues and unions were not investment opportunities; rather, they were like modern trade associations and lobbying groups. To maintain their privileges, they might build fleets of warships or lobby governments to keep out interlopers. Indeed, the Hansa maintained privileged trade zones in several English ports and even helped fund the Yorkists during the Wars of the Roses. In 1407 the English began to carve out a piece of the lucrative wool trade in Northern Europe by chartering their own rival to the Hanseatic League, the Merchant Adventurers. In theory, they were a national company, but most Merchant Adventurers were Londoners. This led to London’s increasing domination of that trade and the gradual decline of other wool ports, like Southampton. During the sixteenth century the Merchant Adventurers and port of London dominated England’s wool trade, which comprised at least three-quarters of the nation’s foreign trade. Before 1550 they shipped mainly raw wool to the continent for finishing; increasingly after 1550 finished wool cloth in England itself. The wool was sent from London to some great European port, usually Antwerp, where it was distributed to the continent. The Merchant Adventurers persuaded Parliament to wrest English trading privileges from the Hanseatic League in 1553, grant them a monopoly on cloth exports in 1564, and have the Hanseatic merchants expelled from England altogether in 1598.