Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (62 page)

Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

This should sound familiar. If Oliver Cromwell looks, in retrospect, very much like a king without a crown, his followers would have agreed. In 1657 they sought, via a document entitled

The Humble Petition and Advice,

to rectify the omission by offering him the title of king and the power to appoint both his successor and the members of an “Other” or “Upper House,” obviously resembling the House of Lords. Cromwell refused the title but accepted the powers along with reinstallation as protector, complete with a gold scepter and purple and ermine robe. It should be obvious that after nearly 30 years of constitutional experimentation, 10 of them without a king, many in the ruling elite longed for the old structures (and strictures). This became even clearer after Cromwell’s sudden death from pneumonia and overwork on September 3, 1658. Like a king, he was given an elaborate State funeral patterned on that of his Stuart predecessors. Like a Crown prince, his eldest surviving son, Richard (1626–1712), was allowed to succeed to the position of lord protector.

The Restoration, 1658–60

Richard Cromwell’s smooth accession suggested that Oliver had left the Protectorate secure. But the new protector inherited three peoples divided in politics and religion and a regime both financially exhausted and increasingly unpopular. The nobility and gentry, in particular, resented not only the Protectorate’s tax burden but also the usurpation of their former place as the State’s representatives in the localities by Puritan nonentities. When not oppressed by the major-generals, they feared the breakdown of social and religious order described in the previous section. In short, the ruling elite had had their fill of godly reformation, whether purveyed by wild-eyed preachers, independent congregations, saintly parliaments, or oppressive armies. Increasingly, and somewhat myopically, the country – or at least the traditional ruling class – began to long for the good old days under the Stuarts. Only a man of strength and conviction like Oliver Cromwell could have held the nation together and maintained his regime in power under such circumstances.

Unfortunately for that regime, Richard was no Oliver. Richard Cromwell was, in fact, an intelligent, amiable, thoroughly decent man who would soon lose control of events. In the spring of 1659 Parliament attempted to assert its authority over the Council of the Army. This led the army to force another dissolution of parliament, banish Richard into retirement, and recall the 78 surviving members of the Rump. The Rump, quite naturally, also sought to control the army, which, true to form, sent it packing on October 13, 1659. The diarist John Evelyn (1620–1706) expressed the general feeling of uncertainty when he wrote: “The army now turned out the Parliament…. We had now no government in the nation, all in confusion; no magistrate either owned or pretended, but the soldiers and they not agreed: God Almighty have mercy on, and settle us.”

32

In late October, a Committee of Public Safety headed by General Charles Fleetwood (ca. 1618–92) established, in effect, rule by the Grandees. But most of the generals appointed didn’t even bother showing up. By Christmas Fleetwood had thrown up his hands and resigned power back to the Rump. At this point, General George Monck (1608–70), the ranking commander in Scotland, began to march south with the only fully paid army in the British Isles. No one knew what he would do but each group – Republican, Royalist, Presbyterian, Independent – seems to have hoped that he was one of them.

He reached London in February 1660. After some vacillation, on February 11 he ordered the Rump to call for immediate elections, thereby dissolving itself, with or without the return of the members secluded in 1648. The populace greeted this news with joy – expressed that night by the roasting of rump steaks in the streets of London. The secluded members returned on February 21 and, on March 16, the full Long Parliament ordered new elections and dissolved itself. Simultaneously, the exiled Prince Charles, sensing his moment, and hoping to sway the election, issued from the continent the Declaration of Breda. This promised amnesty to all who had participated in the Civil Wars apart from those to be excepted by Parliament; liberty “to tender consciences” (freedom of religion), also subject to parliamentary approval; and the recognition of all land sales since 1642. These provisions were designed to allay fears that a restoration would bring political, religious, or economic revenge. Thus, Charles sought to begin the healing of old wounds and to present himself as a consensus choice who would be fair to all, not just former Royalists.

It worked. The Parliament elected in April 1660, known as the Convention Parliament because no monarch had convened it, was overwhelmingly moderate in composition. That is, it was dominated by Royalists and Presbyterians, the latter of whom now supported the Stuarts as their best hope to restore order and good government. When Parliament met at the end of the month, it issued an invitation for the exiled prince to return as sovereign. It proclaimed him on 8 May and dispatched a fleet to bring the nation’s favorite son home. On May 29, 1660, coincidentally his birthday, King Charles II (reigned 1660–85) entered London accompanied by Monck, newly created duke of Albemarle and master of the Horse, as well as aristocratic supporters, both old and new. This time, Evelyn wrote far more optimistically, even triumphantly:

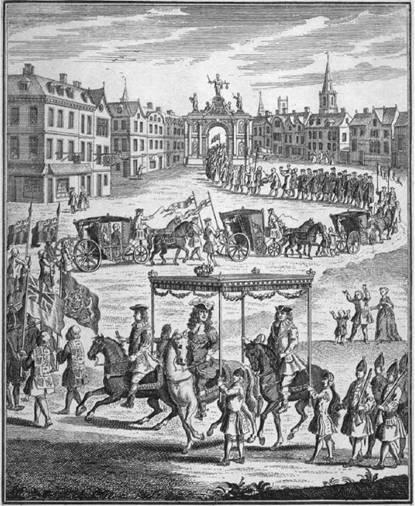

This day came in his Majesty, Charles the 2d to London after a sad and long exile, and calamitous suffering both of the King and Church: being 17 years. This was also his birthday, and with a triumph of above 20,000 horse and foot, brandishing their swords and shouting with unexpressable joy: the ways strewed with flowers, the bells ringing, the streets hung with tapestry, fountains running with wine: the mayor, aldermen, and all the companies in their liveries, chains of gold, banners; Lords and nobles, cloth of silver, gold, and velvet everybody clad in, the windows and balconies all set with ladies, trumpets, music, and myriads of people flocking the streets and was as far as Rochester, so as they were 7 hours in passing the city.

As described above and depicted in a contemporary print (see

plate 18

), it was as if the Great Chain of Being had not only been restored but was laid out in person, horizontally, end to end, from Rochester to London, in all its glory. No wonder that Evelyn, a devout member of the Church of England and a landed gentleman who had lost much during the preceding revolution, wrote, “I stood in the Strand, and beheld it, and blessed God.”

33

The old order was restored, the clock turned back. The people of England had experienced a long national nightmare, a winter of profound discontent which had reached its nadir on a cold January day in 1649. They now awakened in springtime to find themselves in love with their new, young sovereign of the old Stuart line.

Or did they? Could the English really “go home again”? Could either Charles Stuart or the people who now embraced him with open arms ever entirely forget that they had publicly vilified and executed the last Charles Stuart, his father; broken the Great Chain; smashed the Tudor–Stuart constitution in Church and State; tried out several new forms of government, a free press, and religious toleration; and considered unorthodox social and religious systems? Could the English constitution and the people it was meant to govern really go back to 1603, or 1625, or even 1641? Could they forget the many years when the House of Commons had ruled on its own – effectively, if tyrannically – without king, lords, or bishops? Put another way, had the Civil Wars and Restoration really done anything to solve the problems that had led to them, those of sovereignty, finance, foreign policy, religion, and local control? The answers to these questions were uncertain on that brilliant May day in 1660. In fact, they would take most of the next half-century to be resolved.

Plate 18

The entrance of Charles II at the Restoration, 1660. Mary Evans Picture Library.

CHAPTER NINE

Restoration and Revolution, 1660–1689

At first glance, the Interregnum and Restoration seem to have resolved none of the questions over which the British Civil Wars had been fought. Rather, after so many bloody battles, revolutions in government and religion, the deposition and beheading of a king, and an experiment with a republic, in 1660 the English people appear to have opted to go back to square one: the restoration of the constitution in Church and State more or less as they were before the Civil Wars. In fact, the Restoration settlements only

seemed

to turn the clock back. This appearance of

déjà vu

sometimes left contemporaries confused – and, increasingly, bitterly divided – about the meaning of the dramatic events through which they had just lived.

This is not to say that the Civil Wars, their onset and aftermath, settled nothing. The upheavals of the past three decades had taught the English ruling class three hard lessons. First, while they had not settled the sovereignty question, it was now established that the English constitution required

both

king and Parliament. Unfortunately, this still left open the question of which was to predominate. For Evelyn and old Cavaliers, the more specific lesson was clear: kings might err, but they were still semi-sacred beings whose authority was not to be questioned. To kill the king, as the revolutionaries had done in 1649, was to sin against the universal divine order. For the Royalists, the chaos of civil wars, revolution, and interregnum demonstrated clearly the fatal effects of abandoning the Great Chain of Being. Eventually, these beliefs, married to loyalty to the Church of England, coalesced into the ideology of one of the first political parties, the

Tories

. But for old Roundheads the events of 1629–60 held a different lesson: that Parliament was the true guarantor of English liberties. The 1630s, in particular, had proven that body an integral and necessary part of the English constitution as much as the 1650s had proven the need for a king. Some went further, arguing that the past quarter-century had taught that kings were not gods but men; therefore, a bad king could and should be deposed. This implied the sovereignty of Parliament and, by extension, the people whose interests it, theoretically, represented.

Contemporaries holding these opinions, and tending to favor toleration for all Protestants, would eventually form an opposing political party known as the

Whigs

. In other words, the question of sovereignty, and by implication the related questions of finance, foreign policy, religion, and local control, would continue to divide English men and women at court, in parliament, and in the country at large.

Perhaps religion above all: the second lesson taught by the Civil Wars and learned by the ruling class of England was that Puritans could no more be trusted with political and religious authority than Catholics. From henceforward they, too, would be associated with political and religious extremism: king-killing, republicanism, toleration of outlandish sects, intolerance toward beloved ceremonies and traditions. This does not mean that Puritans would cease to be an important force in English life, despite their apparent defeat in 1660. On the contrary, it means that religion would also continue to fracture the nation as Puritans, like Catholics, faced proscription and persecution. If the Civil Wars clarified, but failed to solve, the questions of sovereignty, finance, foreign policy, and local control, they rendered that of religion even more complicated and dangerous.

One more thing became clear as a result of these experiences: the vast majority of the English ruling elite had become strongly averse to using violence, or making common cause with the common people, in order to effect constitutional or political change. The past quarter-century had proven that such expedients were just too unpredictable, too dangerous to their own interests. Since the tensions which had led to those expedients were not yet resolved in 1660, this raised the pressing question of how such change was to be effected in future. The Convention Parliament would begin the attempt to solve each of these problems.

The Restoration Settlements, 1660–5

Given the lack of consensus about what the Civil Wars had meant, the English Restoration was bound to be a compromise.

1

It did not restore the monarch’s powers as they were in 1603 or 1640 but as they had been modified by the Long Parliament in 1641. Still, this was mostly good news for the new king, Charles II. First, he was restored to executive power. That is, the king could once again conduct foreign policy as he saw fit. According to the Militia Acts of 1661 and 1662, he, and only he, could call out that body – an issue that had been disputed on the eve of the Civil War. He could appoint what ministers he wanted and he could remove judges at will. He could, moreover, dispense with the law in individual cases and, theoretically, suspend it during national emergencies. Finally, he could summon, prorogue, or dismiss Parliament with much the same freedom as his predecessors had exercised, within the limitations of the Triennial Act. That is, he was merely required to convene it for a brief meeting once every three years.