Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (69 page)

Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

Plate 21

Mary of Modena in Childbed,

Italian engraving. Sutherland Collection, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

The Glorious Revolution, 1688–9

In fact, William had been considering invasion for some time. He had three reasons for accepting the invitation in the early summer of 1688: to protect Mary’s rights to the throne; to keep England from turning Catholic and allying with France; and to bring the increasing wealth and power of the British Isles onto the Dutch side in their fight for survival against Louis XIV. It took most of the rest of the summer, and all the financial and personal credit William possessed, to assemble a force consisting of about 21,000 foot, 5,000 horse, at least 300 transports, and 149 warships – greater than the Armada – by the time of its departure on November 1. These ground forces were more than matched by James’s English army of, perhaps, 40,000, but it was spread around the three kingdoms. Moreover, James’s forces had only drawn blood against frightened townsmen and peasants at Sedgemoor. William’s troops – largely Dutch, but including foreign mercenaries and exiled English Whigs – were battle-hardened by years of fighting against the French, generally considered to be the best army in Europe.

In other respects – and unlike the Spanish a century before – William got lucky. First, despite the warnings of his advisers, James initially refused to believe that his son-in-law would take arms against him. As a result, he refused French naval help. Second, Louis, trusting James’s instincts, decided to launch an invasion of Rhine-Palatine in September (see

map 12

). This tied up his forces for the autumn and winter, making it impossible to take advantage of William’s absence by invading the Netherlands instead. Even the weather cooperated with the prince of Orange. In November, the wind shifted, blowing William’s ships across the Channel and keeping James’s fleet bottled up in the mouth of the Thames. As a result, William of Orange landed unopposed in the southwest of England on November 5, 1688 – the day after his birthday and the anniversary of the failed Catholic Gunpowder Plot of 1605. Thus, not only the weather but also the calendar seemed a good omen for the Protestant side.

On the Catholic side there was a loss of nerve. Finally realizing the seriousness of William’s preparations, in late September James tried to back-pedal, abolishing the Ecclesiastical Commission, restoring the old city charters and their Anglican Tory oligarchies, and promising to call a free parliament. This did nothing to placate the Tory clergy or gentry or attract Whig townspeople; instead it demoralized Catholics and threw the local government of the nation into confusion. Soon after hearing that William had landed, James developed a massive nosebleed – probably a psychological reaction. At first glance, the king’s panic makes no sense. He had at his immediate disposal 25,000 troops encamped on Salisbury Plain, squarely between William, at Exeter, and London. His coffers were full. He had “home-field” advantage. And there had not been a successful invasion of England since the Wars of the Roses. James should have been able to throw William into the sea in a matter of weeks, if not days. But he must have realized that his forces were largely untested and divided in religion and loyalty. Nor could he have been encouraged by his own obvious personal unpopularity. Perhaps his father’s fate haunted him.

In the meantime, the country hesitated between safety and hope. In particular, the ruling elite seems to have taken a wait-and-see attitude to William’s invasion. But as James hesitated to act, his support began to evaporate. The first to go over to William was Edward Hyde, Viscount Cornbury (1661–1723), the king’s own nephew. By mid-November, the lords lieutenant who had been asked to raise the militia did so – and then marched it over to the prince of Orange: Lord Delamere (1652–94) gave his Cheshire tenants a choice, “whether [to] be a Slave and a Papist, or a Protestant and a Freeman.”

15

Thus, at the moment of crisis James II turned out to be vulnerable on the last long-term issue that had cost his father the crown, that of local control. Ultimately, that control still rested with the landed aristocracy who held estates in the localities. In the course of two successive mornings between November 23 and 25, James awakened to find that his other son-in-law, Prince George, his dearest friend, Lord Churchill, and the head of the most staunchly Royalist family in England, James Butler, second duke of Ormond (1665–1745), had gone over to William. On the 26th he learned that Princess Anne had also fled the court, leading James to lament, “God help me … my own children have forsaken me.”

16

At this point the king decided that the game was up. He abandoned his army and hurried back to London by coach. Once there, he put Queen Mary Beatrice and Prince James into a boat for France. On the night of December 11 he threw the Great Seal (required for registering statutes) into the Thames and attempted to make his own escape. He botched even this when he was discovered, disguised, while attempting to board a boat for the continent. The king returned briefly to London but, despite the urging of a number of Tory peers, he had no intention of staying. By the same token, William had no desire to see his inconveniently returned father-in-law. So, when James requested to go to Rochester, on the extreme east coast of Kent, there were no objections. The unfortunate monarch took advantage of this location and made his second, successful, escape attempt on December 23. The Restoration Settlement was at an end.

Put another way, the Great Chain of Being had been broken once again within a generation. The ruling elite understood that, in the king’s absence, someone had to run the country. Chaos threatened as Londoners attacked Irishmen and burned Catholic property. On December 24, 1688 an assembly of 60 peers asked the prince of Orange to administer the government temporarily, until a new settlement could be worked out. On December 26, 300 former members of the House of Commons, joined by London’s civic leaders, agreed. These peers and former MPs called for a second Convention Parliament to decide the disposition of the Crown; it first met on January 22, 1689. The Whigs elected to this Convention came to an early and easy decision. Since they believed in a contractual basis for governmental authority, in the right of revolt against a bad ruler, and in the supreme power of Parliament, they had no trouble asserting that James had broken his contract with the English people and had been deposed. In their view, Parliament had every right, as the people’s legitimate representative, to have excluded James from the throne 10 years before, and to grant it to William now. On the other hand, Tories, who had been raised on the doctrines of the Great Chain of Being, the Divine Right of monarchy, passive obedience, and non-resistance, and who had supported the Stuarts through thick and thin with their very lives and fortunes, were appalled. It is true that they had opposed James in religion, and many had supported William’s invasion, but in the hope that he would curb his father-in-law’s folly, not usurp him. Despite his flight, was not James II still the one, true, and rightful king? In short, while the Whig position was eminently rational and practical, that of the Tories was romantic and emotional. The latter proposed a number of fictions to enable them to hang on to their beloved notions of hereditary monarchy and Divine Right. First, they suggested that James remain king in name, with William as his regent. But James was unlikely to accept such an empty crown. Next, they suggested that the crown be vested in Mary, who was at least a Stuart (and even the rightful heir,

if

one accepted the fantasy that James II’s “son” had been smuggled in a warming pan). To this suggestion, William replied that he had no interest in “being his wife’s gentleman usher.”

17

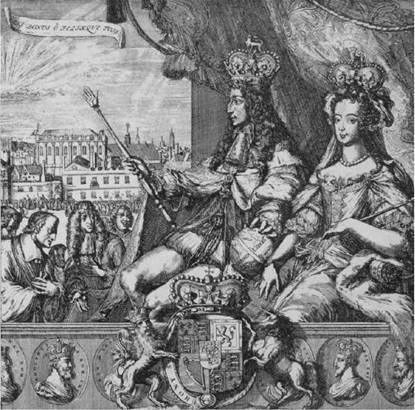

Increasingly, it became clear that William of Orange would take his army and go home, leaving the English to their fate, if they did not offer him the main prize. Finally, after two weeks of heated debate, at the beginning of February the Convention Parliament agreed that James II had “abdicated” the throne, and that it was thereby “vacant.” On February 13, 1689, in the Banqueting House at Whitehall, site of Charles I’s execution, William and Mary were offered the crown jointly, with administrative control to be vested in the former (see

plate 22

). They thus became William III (reigned 1689–1702) and Mary II (reigned 1689–94). At the ceremony, the dual monarchs were also offered a document, the

Declaration of Rights

, which condemned the suspending and dispensing powers, royal manipulation of the judiciary, taxation without parliamentary permission, and the continuance of a standing army. It also reaffirmed the subjects’ right of petition and the necessity of free elections. Historians have argued ever since as to whether the

Declaration

was a contract; that is, whether the offer of the crown was conditional on their acceptance of this document. In fact, it does not matter. Clearly, for the first time in English history, Parliament had chosen a king and a queen.

So much for the settlement of the crown which James had squandered. What about the Church which he had, in contemporary eyes, attacked? Remember that upper-class Englishmen had revolted not because they wanted a different king or constitutional settlement but because the current king, enabled by his vast constitutional powers, was attacking the Protestant ascendancy. More specifically, Anglican Tories revolted because they wanted to preserve the religious status quo, in particular the position of the Church of England as the national Church – indeed, really the only legal Church – in England. Whig Dissenters had been offered toleration by James II, but many had refused. They had revolted against him because they felt that Catholic emancipation was too high a price to pay for their own freedom. Since the leading Dissenters had thus, by and large, remained loyal to the Protestant ascendancy even against their own immediate interests, and since Dissenter goldsmith bankers and merchants provided William’s government with crucial financial support immediately after the Revolution, Anglicans were going to have to reward them with concessions. In effect, Dissenters could argue that they had atoned for their extreme and violent behavior during the Civil Wars and Interregnum. Strengthening their argument was the further inconvenient fact that the new king was himself not an Anglican but a Dutch Calvinist – in other words, in an English context, a Dissenter. As a result, in 1689 the Convention Parliament passed the Toleration Act. Henceforward, virtually all Trinitarian Protestant Churches were to be tolerated; most of the penalties of the Cavalier Code were removed.

18

The chief remaining obstacle faced by Dissenters was the Test Act. This was very important psychologically, but, as we have noted, it could be got round by the practice of occasional conformity. That is, upon appointment and biannually thereafter, all a Dissenting officeholder had to do was set aside his religious sensibilities and communicate in an Anglican service. Catholics, of course, could do no such thing; they remained subject to extensive penal legislation.

Plate 22

Presentation of the Crown to William III and Mary II,

by R.

de Hooge after C. Allard. Mary Evans Picture Library.

So what does all this mean? Why did contemporaries come to refer to the Revolution of 1688–9 as “Glorious”? Why do historians see it as one of the most significant events in all of British history? The first question is easily answered. The Revolution was glorious, first, because relatively few people got hurt: this was, apart from about 50 lives lost in skirmishing, the victims of the “Irish-nights” in London, and James’s free-flowing nose, a bloodless revolution in England. (It was quite another story in Ireland, Scotland, or the colonies.) Moreover, while all seemed to be in confusion at the time, in retrospect the relatively non-violent and almost orderly course of the Revolution caused it to seem inevitable, even God-ordained. After all, it happened in the magical year of 1688, an exact century after the defeat of the Spanish Armada. As in 1588, a Protestant wind had apparently saved England at the eleventh hour. Furthermore, William’s landing took place on November 5, another red letter anniversary of Protestant deliverance, this time from the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. There was, too, the rapidity with which James’s Catholic regime collapsed and the fact that it did so without the sort of long-drawn-out social revolution that had, in upper-class eyes, blighted the British Civil Wars at mid-century. This time, the top link of the Great Chain had been broken, yet the subordinate links had held. This time, the ruling class had remained in charge; the lower orders had done what they were told. No Levellers, Ranters, or Fifth Monarchists came out of the woodwork to push their radical utopias. All these things rendered the events of 1688–9 a “Glorious Revolution” in the eyes of its makers.