Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (76 page)

A grateful queen rewarded Marlborough by granting him the royal manor of Woodstock. Parliament rewarded him by funding the construction of a magnificent palace there called, appropriately enough, “Blenheim.” The emperor rewarded him with the title of prince of the Holy Roman Empire. Far more important than these honors, the British ruling class finally got behind the war. Thomas Coke, a Tory MP from Derbyshire, wrote in response to Marlborough’s bold march: “the country gentlemen, who have so long groaned under the weight of four shillings, in the pound, without hearing of a town taken or any enterprise endeavored, seem every day more cheerful in this war.”

14

This was good news for the Whigs, who did well in the parliamentary elections of 1705 and 1708. The Tories, frustrated, grew increasingly desperate. In 1704 they offended the queen and nation by attempting to tack a clause banning occasional conformity onto the annual bill for the Land Tax: that is, they would hold funds for the war hostage unless Parliament did their bidding on the religious issue. Failing in this, they insulted Anne in 1705 by moving in parliament that the Church was in danger under her administration. Failing once again, they infuriated her in the same session by moving that a member of the Hanoverian family be invited over to live in England until the queen died. They did not do this because they were committed Hanoverians. Rather, they sought to put the queen into an embarrassing position. Like Elizabeth before her, Anne naturally saw such a plan as morbid and dangerous to her interests, but how could she refuse without looking like a Jacobite? In the end, all the Tories succeeded in doing was convincing Anne that they were irresponsible and untrustworthy. Even before Blenheim, she had begun to employ more Whigs in her government, and she continued to do so in 1705 and 1706. Gradually, and sometimes against her will, the Junto began to return to power, to prosecute Queen Anne’s war as they had done King William’s.

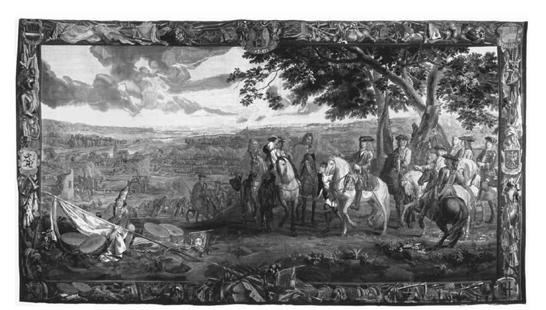

Plate 24

The battle of Blenheim. By kind permission of His Grace, the Duke of Marlborough.

The Whig resurrection between 1704 and 1710 had important repercussions both at home and abroad. First, Whig parliamentary majorities guaranteed that the war would continue to be funded liberally. As a result, by 1708 Marlborough, Godolphin, and the government they headed grew ever more dependent on the Whigs. The Whigs’ financial generosity combined with Marlborough’s brilliant generalship led to a succession of victories against the French: at Ramillies in 1706, Oudenarde in 1708, Malplaquet in 1709, and Bouchain in 1711. Nor were Britain’s allies idle. In 1706 Prince Eugene swept the French out of Italy (see

map 13

). In 1703 the Allies opened a second front in Spain itself. At first they succeeded here as well, capturing Gibraltar and defeating the French fleet at Malaga in 1704, then taking Barcelona in 1705 and Madrid in 1706. But the war in Spain overextended the Allies, who were also fighting at sea and in North America as well as in northern Europe. Moreover, the largest portion of the Spanish people, the Castilians, favored Felipe V. As a result, the Allied forces suffered two disastrous defeats, at Almanza in 1707 and Brihuega in 1710. These virtually guaranteed that the Bourbon Felipe, not the Habsburg Charles, would occupy the Spanish throne. Still, this was Louis’s only major success; the Grand Alliance stymied him on every other front and in every other war aim. By the end of the decade, Marlborough’s victories and the sheer expense of fighting a world war against the British financial juggernaut had just about brought the Sun King to his knees.

At home, the Whig ascendancy at court and in Parliament enabled that party to pass legislation to safeguard the Protestant or Hanoverian succession. In 1706, they responded to the Tory demands for a Hanoverian to live in Britain by securing passage of the Regency Act. Instead of subjecting Queen Anne to the discomfort of her successor’s presence on site, this legislation established a Regency Council, to be stocked with staunch pro-Hanoverians, to act as an executive and to ensure a smooth transition on her death. As a further safeguard, Parliament was to remain in session following that event for six months. Thus were the Tories outmaneuvered and the Protestant succession strengthened. Incidentally, this legislation also repealed the provision of the Act of Settlement which forbade government officers from sitting in Parliament: the Whigs knew that they would be the court party under a Hanoverian, and they wanted to ensure that they controlled both the legislature and the spoils of government.

More importantly, in the following year the Whigs pushed through an Act of Union with Scotland. As we have seen, James I’s attempts to knit the two countries together a century previously had been thwarted by age-old prejudices between the two peoples, and some real concerns about incompatible legal systems. Cromwell had united the two nations from 1654 to 1660, but few people on either side of the Tweed wanted to repeat that shot-gun marriage. The Revolution of 1688–9 did nothing to heal Scotland’s longstanding disunity, while drawing it into the orbit of European-wide conflict. King William’s war disrupted Scottish trade, especially with France. Worse, the English Navigation Acts continued to treat the Scots as if they were the Dutch or the French. No Scottish merchant could trade with the English colonies but in an English ship and through an English port. When the Company of Scotland tried to set up its own trading colony in 1698, at Darién on the isthmus of Panama, Spanish and English hostility was so intense that it failed, with the loss of some 2,000 lives and perhaps a quarter of Scotland’s monetary capital. This took place in the middle of five disastrous harvests, leading to a real subsistence crisis, between 1695 and 1699. During this period, famine and emigration reduced the population between 5 and 15 percent. To some, it appeared that the English were trying to starve their northern neighbors out of existence.

Queen Anne’s accession did nothing to ease these resentments. In 1703, the Scottish Parliament passed a series of anti-English laws. The Act Annent Peace and War decreed that, after Anne’s death, all foreign policy decisions from London would have to be approved by a Scottish parliament. The Wine Act and Wool Act allowed for Scottish trade with France even during hostilities. Finally, and most alarmingly to the English, the Act of Security stated that in the event of Anne’s death, a Scottish parliament would elect her successor in Scotland. The implied threat was that they would choose the Pretender, Prince James. This meant that, even if the English Acts of Settlement and Regency worked south of the border and the Whigs secured the accession of a Hanoverian in England at Anne’s death, the Scottish Act of Security might install his Catholic, pro-French Stuart cousin north of it. This would revive the “Auld Alliance” between Scotland and France, give the latter a foothold on the British mainland, and threaten the Revolution Settlement and the gains of Blenheim.

Once the Whigs achieved power in London, they pursued the only clear solution to this dilemma: a union of England and Scotland. This was easier said than done, given English prejudice toward the Scots, Scottish resentment toward the English, Scotland’s disunity, and the understandable reluctance of its people to lose their national identity and be absorbed by their wealthy neighbor to the south. In the end, that wealth won the day, on two counts. First, the Whigs offered the economic advantages of being let into the English trading system. Henceforward, the English and Scots would trade as part of one British nation, open to all the wealth of the new British Empire. This message worked on Scottish MPs, merchants, and landowners who depended on the cattle trade with their rich neighbors to the south. English wealth assisted in a second, more direct, way: bribery. Scotland itself was to receive “the Equivalent,” a one-time payment of £398,085. More quietly, many individual Scots peers and MPs happily took bribes in return for voting their nation and its parliament out of existence; as one English minister crowed: “We bought them.”

15

Still, the Scots did win some real concessions. In the new London-based Parliament of Great Britain, Scotland would be represented by 16 peers, elected from among the total Scottish peerage, and 45 MPs. This was proportionally somewhat lower than Scotland’s population compared with that of England (few, other than the Levellers [see chapter 8], even considered proportional representation before the late eighteenth century). But it was much higher than the Scottish contribution to the war merited as against that of England. Scottish landowners were required to pay only one-fortieth of the Land Tax; their proportion of the Excise was 1:36, yet there was one Scottish MP to every 11.4 from England and Wales. Furthermore, the northern kingdom would retain Scottish law and, of course, the privileged status of the Presbyterian Kirk. The Act of Union, creating the state of Great Britain, was passed in the spring of 1707; the first Parliament of Great Britain met that autumn.

Despite the concessions noted above, many Scotsmen, particularly Tories, were unhappy with the union. England and its capital would dominate the new state of Great Britain politically, socially, and culturally, often treating the Scots as if they were second-class citizens. But most historians would nevertheless argue that the union was good for Scotland. Economically, it laid the groundwork for a gradual upsurge of prosperity in the eighteenth century. That led, in turn, to a cultural flowering, largely based in the big cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow, which is sometimes called the Scottish Enlightenment. It is difficult to see how this could have happened in an independent and economically isolated Scotland under the control of the Catholic branch of the Stuarts. For England and the Whigs, the Union’s major advantage was that it made more certain the Hanoverian succession.

The Act of Union was the high-water mark of Whig success under Queen Anne. As the reign wore on, the Whigs, and their Junto leaders in particular, became increasingly unpopular with Anne and with the country at large. This was due, in part, to their overconfidence and ambition, in part to a shift in the country’s mood on some of the major issues which separated the two parties. First among these was the war and its related issue, money. In the beginning, Marlborough’s succession of victories over the French had been greeted with universal approbation, the queen and court processing through the streets of London to St. Paul’s Cathedral for elaborate services of national thanksgiving. But after a while, the queen and her subjects began to wonder why no victory seemed to be decisive; why the French were never brought to the negotiating table. After the battle of Malplaquet in 1709, which saw the loss of nearly 35,000 men on both sides, she is supposed to have remarked: “When will this bloodshed ever cease?”

16

In fact, toward the end of the decade, nature gave the Whigs a chance to make peace. The harsh winter of 1708–9 resulted in a terrible harvest, reducing the French peasants who paid the bulk of Louis’s taxes to near starvation. The Sun King’s funds ran dry. He was actually forced to melt down the silver furniture at Versailles. Finally, in March 1709, he opened negotiations for peace. It is a measure of his desperation that his diplomats came to the peace conference in the Netherlands willing to concede Spain, Italy, the Indies, fortress towns on the Dutch border, and the Protestant succession. But this was not enough for the Whig diplomats. They made further, incredible demands: not only that Louis’s grandson give up his claim to the Spanish throne, but that, if Anjou refused, Louis himself should forcibly remove him from Madrid with French troops. To this the French king replied that if he was required to make war, he would rather do so against the British than his own children. The peace talks collapsed. At this point the Tories began to charge, and many English men and women began to believe, that Marlborough, Godolphin, and the Whigs were intentionally prolonging the war to keep themselves in power and to get rich off the sale of army commissions, government contracts, lotteries, and the funds. Thus, old country fears of standing armies and resentment of high taxes combined with prejudice against the rise of new men. These charges were probably unfair. Rather than consciously seeking to prolong a profitable war, the Whigs were more likely blinded by their longstanding fears of France and Catholicism. They failed to realize that the Sun King was effectively finished. They had been so afraid of him for so long that they fought on past the point of reasonableness.

The second issue upon which the Whigs misjudged the mood of the country was religion. Remember that most English men and women were Anglicans, and somewhat distrustful of occasionally conforming Dissenters. In 1710, the Whig government decided to prosecute a prominent Anglican clergyman named Henry Sacheverell (ca. 1674–1724) on a charge of seditious libel. Sacheverell was a High Church Tory rabble-rouser who had preached on November 5, 1709 – the anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot and William’s landing at Torbay – in favor of passive obedience and non-resistance. The sermon,

The Perils of False Brethren in Church and State,

was an implicit attack on the Revolution of 1688–9 and, by extension, the whole course of English history over the last 20 years. Sacheverell went on to decry the Marlborough–Godolphin ministry, Whigs, Low Church Anglicans, and occasionally conforming Dissenters as “double-dealing, practical atheists” and “bloodsuckers that had brought our kingdom and government into a consumption.”

17

The sermon was printed, reaching 100,000 copies and sparking a partisan religious debate that reached 600 titles on the subject within a year. Sacheverell’s words were stupid ones to say in public; but to prosecute their author for saying them was even more stupid. In December, the Whig government launched a parliamentary show trial of Sacheverell. The government thought that it was defending “Revolution Principles”; but many Anglican Tories saw the trial not as a referendum on the Revolution but as Whig persecution of a poor Church of England clergyman. When the indictment was announced on March 1, 1710, ordinary Londoners rioted (

plate 25

). They took out their frustrations by tearing down Dissenting meeting houses, many of which had been built and frequented by the new monied men. Clearly, in religion as well as war, the Whigs were pushing their luck.