East Side Story

Authors: Louis Auchincloss

Louis Auchincloss

Table of Contents

Houghton Mifflin Company

BOSTON NEW YORK

2004

Copyright © 2004 by Louis Auchincloss

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Visit our Web site:

www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com

.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Auchincloss, Louis.

East Side story : a novel / Louis Auchincloss.

p. cm.

ISBN

0-618-45244-3

1. Scottish AmericansâFiction. 2. Upper East Side (New York,

N.Y.)âFiction. 3. Upper class familiesâFiction. 4. New

York (N.Y.)âFiction. 5. Newport (R.I.)âFiction. 6. Rich

peopleâFiction. 7. SocialitesâFiction. I. Title.

PS

3501.

U

25

E

27 2004

813'.54âdc22 2004047499

Book design by Anne Chalmers

Typefaces: Jansen Text, Copperplate

Printed in the United States of America

MP

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTSFor

J

UNE

D

YSON,

dear friend

and fellow trustee

through many happy years

1.

Peter

[>]

2.

Eliza

[>]

3.

Bruce

[>]

4.

Gordon

[>]

5.

Estelle

[>]

6.

Gordon

2

[>]

7.

Alida

[>]

8.

David

[>]

9.

Jaime

[>]

10.

Ronny

[>]

11.

Pierre

[>]

12.

Loulou

[>]

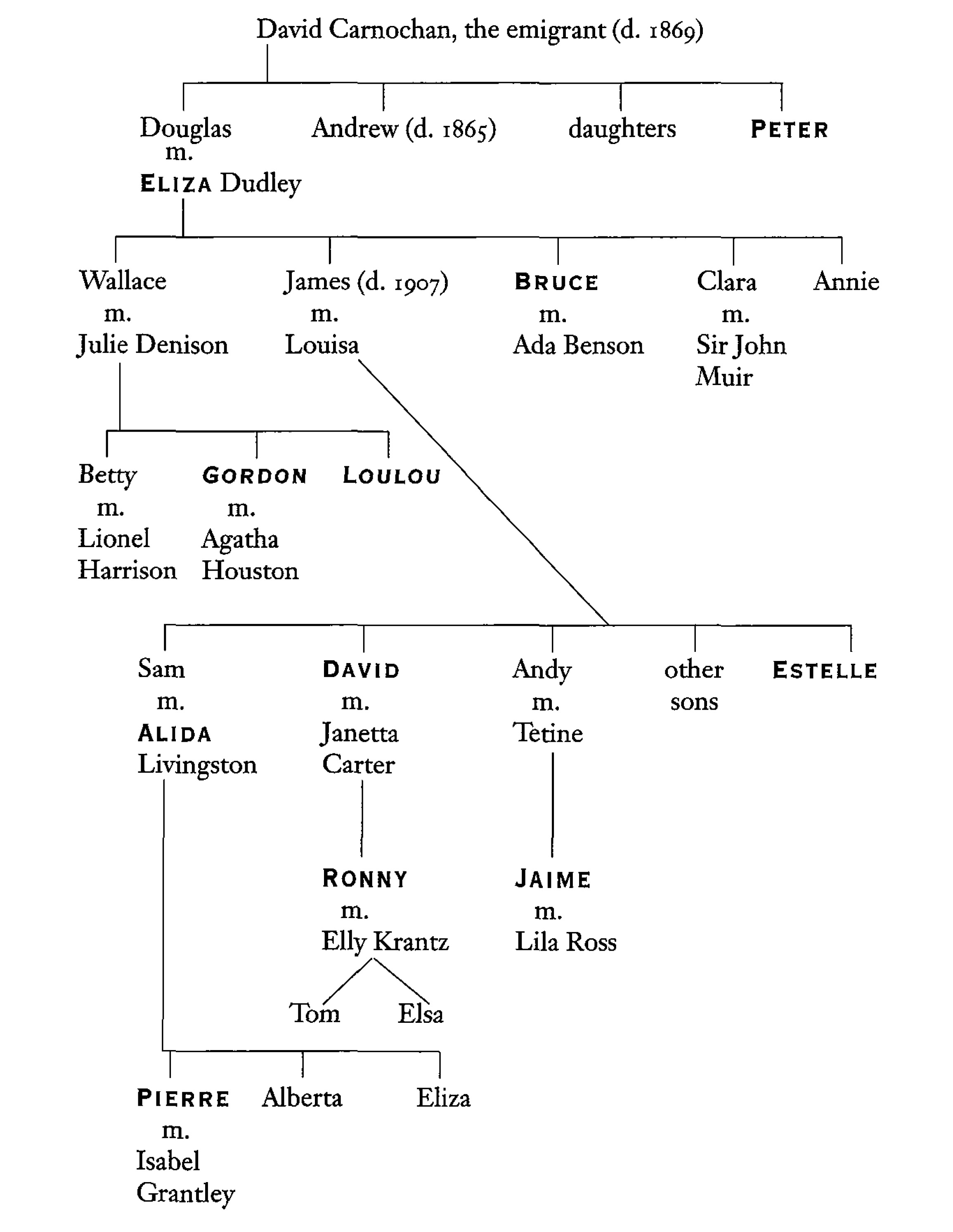

T

O CELEBRATE,

next New Year's Day of the year 1904, the seventy-fifth anniversary of our arrival on this side of the Atlantic, my great-nephew David urged me, as the only published author of the family, to write up a history of the Carnochans to be privately printed and distributed to the many descendants of my father, the original David, who, three quarters of a century ago, emigrated as a young man from Scotland to establish a branch of the family thread business in New York. When I pleaded age and illness as an excuse, he asked me at least to contribute a first chapter about my father, whom I, as the youngest of his offspring, was the sole survivor to remember, pointing out that as the patriarch had left no letters or journal, there would be nothing but account books with which to reconstruct his personality.

But would that be such a bad thing? Father's obituary notices in 1869 were fulsome in their pompous tribute, but I always kept in a special file the funeral address of his Presbyterian pastor, which contained this gem:

He was not a man of smooth words, a disguised flatterer, nor a person to seek even good ends by craft and indirectness. Making no pretensions to literary culture, though well instructed in all that belonged to his profession and his church, he dealt more in forcible reasons than in fair speeches, and this in business as in religion. It is just the sort of character which we should lament to see going out of date. Of any man it is sufficient eulogy to say that he so uses his powers as to be virtuously successful in his chosen calling. Such honor belongs to David Carnochan. The judgment of the commercial circle in this city, as uttered in the great centers of business in our emporium, is decisive on this point.

When I suggested to my great-nephew that he use this for his first chapter, he simply said: "Uncle Peter, you're making fun of me." Yet every word the pastor had written was true! The New York of that simpler day had at least not been hypocritical. It actually believed those things!

Well, I was not going to let myself sink into the role of crank, so I drafted for David a short, dry, factual account of my father's business and domestic life, which will constitute the innocuous preface to his little book. Don't most readers skip prefaces, anyway?

But as I wrote it, I found myself wondering if I shouldn't try my hand at a few pages on what Father was really like, at least as a father. And then I realized that any such portrait would be just as much a portrait of the

son

as the father, for each term implied the existence of the other. Well, why not? It would be the portrait of a relationship, and maybe that was as good a way as any to approach truth.

So here it is. David will never print it in his family book, but something tells me he will not throw it away. David is no fool.

We don't know much about our origins in Paisley. Paisley is an ancient town, set in the plain of the Cart rivers, seven miles west of Glasgow, in Renfrewshire, and a great thread manufacturing center. Some of the family used to take pride in the fact that David the emigrant came of a clan already established in business in the Old World rather than as an adventurous beggar or a refugee from religious persecution or even an ex-convict. But some of our less-reverent youngsters liked to circulate a story about my older brother Douglasâmy father's true heir and prosperous business successorâwhen he returned to the homeland in quest of one of those family trees which (the mockers claimed) Edinburgh genealogists produced at so much a head for each Bruce, Stewart, or Wallace added, and happened to hire an ancient caddy (Scots had such then) at a Paisley golf course. "I am here, my man," Douglas is reputed to have informed the old boy in a lordly tone as they trudged across the green, "to trace my family origins. My name is Carnochan. Perhaps you have heard of it." "I have indeed!" was the caddy's enthusiastic rejoinder. "It's my name! And I do recall that my mither used to say one branch had crossed the ocean and done better!" Despite this suggestion of less than Olympian origin, Douglas returned to New York with a tree bristling with lords and ladies. He always denied the caddy story.

Today the fashion has changed, at least in the younger set, and people like to boast that they stem from sturdier stock, from outlaws and sheep stealers and pirates, but I suspect that the truth is that the Carnochans in the Old World were pretty much what they became in the New: good burghers with a sharp eye for a deal. You would not have found one of them risking a copper penny for Mary Stuart or Bonnie Prince Charlie.

The outline of Father's life that I gave to young David was, of course, factually accurate. Father was considered a success at each of the few things he undertook. He was a prosperous merchant in a town that boasted dozens of even more prosperous ones; he served a term as president of the American Dry Goods Association; he was a revered elder of the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, and he enjoyed a seemingly tranquil marriage to the daughter of a fellow Paisley emigrant on whom he sired a multitude of children. I might here note, for whatever significance it may have, that all his many living descendants stem from only one of these, my brother Douglas. The rest died either childless or unwed.

What I have earlier written makes it pretty clear, I guess, that Father was a granite pillar of respectability. He lived simply but well in a big square red-brick house on Great Jones Street and a summer villa on Staten Island, entertaining frugally his carefully chosen few friends, mostly fellow Scots, and punctiliously attending divine services. He never cultivated the society of Gotham, where he would, in any case, have been considered too dour a guest; it was his son Douglas, whose wife, Eliza, was of ancient colonial stock, who went in for that. Father, needless to add, frowned severely on the frivolities of dancing and drinking and general hilarity. He had his own strict views of what such things led to.

But what I want to get at is what Father was to

me,

his youngest and physically frailest child. He was a tall, lean, gaunt man with large craggy features and thick unkempt gray hairâor is that simply the way I see him, looking back, without a trace of nostalgia, at those early years? No doubt I exaggerate his formidability. Neither of my brothers seemed to feel it as I did. And I admit there was a surprising serenity in his pale blue eyes, and that he never lifted a hand to any of us or even lost his temper, and that there was an air of mild benignity in what I could not help feeling was a basic exemption from the usual family attachments. No, he was not a bad man; there was no cruelty in his firmness, or malice, or even ego in his insistence on domestic obedience. What was it about him, then, that filled me with such unutterable dismay?

What it was, I can now only suppose, was that he resolutely deniedâwith the blind faith of a latter-day John Knoxâthat there was anything but potential evil in all the things that to me made life worthwhile: in love and laughter and merry companionship, in sports and theater, and, worst of all, in art. In short: in pleasure. Life to David Carnochan was something simply to be got through by satisfying the fleshly appetites only with such aliments as were necessary to sustain it and only with so much coition as was needed to maintain it for God's glory on earth. And so he ran a business in thread to shield nudity not only from the cold but from temptation, and used his seed to increase the number of God's chosen. The deity who insisted on his own daily magnification could be counted on for compensation in a future life that was presumably

not

devoid of pleasure, though that pleasure would seem to consist primarily in the hallooing of anthems. When I watched Father, stentorianly out of tune, sturdily raising his voice in a hymn in church, I could not but wonder if this to him was the houri promised the deceased Islamite. I could never imagine him in bed with Mother. Was heaven to be a repetition of a Sunday service?

Of course, there are, and perhaps, alas, always will be, persons who hold such tenets, but Father's power, at least where I was concerned, was in making them seem more real than any other reality that I tried desperately to make out behind them. He simply stripped life of every aspect of color and charm that it might have possessed; he made an arid desert of every fancied oasis. In his flat voice, in the grating of his rare chuckle, in the slight elevation of his bushy eyebrows at any mention of a diversion, he made me wonder if the only feasible thing to do in the world he created was to die. His god may not have been my god, but I believed that his god not only existed but would probably get the better of any god I could conjure up to oppose him.

I did not, however, stand alone against him. I may not have had an ally in any of my siblings, but I had one, fortunately or not, as a reader of these notes may decide, in my mother. Mother's outward appearance was that of just such a wife as a man like Father might seem to need and want. She was large, plain, silent, thin-lipped, utterly conventional, an awesomely efficient matron and housekeeper. She appeared to have no difficulty with her spouse's way of life and gave no hint of not sharing his concept of God and what God expected. As a mother she was always patient with and mildly understanding of the whims and wiles of children, though it was sometimes possible to detect that her slightly tepid maternal feelings were in hidden conflict with a repressed exasperation. Except where the two younger of her three sons were concerned: Andrew and myself. Andrew, handsome, hearty, jovial, and charming, was her obvious favorite. He was everyone's favorite; even Father's, whose opaque glance showed almost a twinkle when Andrew smiled at him. The exception granted me was for a very different reason. From childhood I suffered from asthma.

My terrible attacks of breathlessness were allayed only by Mother's care and embraces. She had given life to my siblings, but I was the only one who seemed to need her to retain it. I think I may have represented to her the one thing in the whole Presbyterian world of her husband that she might call her very own, and she was determined to cling to me with a fierceness, always deep within her but hitherto untapped, before which even Father quailed. She raised a wall around my sickbed against which he would have battered in vain, had he not rather had the sense to wait for the day when I should emerge into more neutral territory.

It was thus that I grew up sheltered, so to speak, like a lion cub against a possibly dangerous sire. Or to use a less violent image, like the young Achilles reared amid the maidens, in my case my older sisters, to shield him from future battles. With the marked difference that Achilles managed still to grow up to be a warrior while I became the very reverse. At twenty, as a day student at Columbia College, I was thin and pale and drawn-looking. My attacks had almost ceased, but I made the most of those that still occurred, knowing that too much of a cure might cost me my exemption from the paternal rites of cold baths, vigorous walks on the hard city pavements, two-hour church services, and other soul-fortifying exercises. To me was permitted, in town, the luxury of long winter afternoons by the parlor fire with a treasury of romantic novels, and, in summer, the delight of not having to plunge into the sea but basking in the sun, daydreaming and watching the others bob in the water.