Eating Crow

Authors: Jay Rayner

SIMON & SCHUSTER

SIMON & SCHUSTER

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. The author would like to apologize if there are any such coincidences.

Copyright © 2004 by Jay Rayner

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

Jay doesn’t want to do this, but his lawyers say he must. He’s really sorry.

He also wants to apologize for the size of this print. It’s tiny, isn’t it?

S

IMON

& S

CHUSTER

and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rayner, Jay.

Eating crow : a novel / Jay Rayner.

p. cm.

1. Food writers—Fiction. 2. Restaurants—Fiction. 3. Remorse—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6068.A9493E37 2004

823 .92—dc22 2004045281

.92—dc22 2004045281

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-9130-6

ISBN-10: 1-4165-9130-3

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

For Matthew, Lindsay and Lois Fort,

and for Jim Albers Jr.

eating

crow

I

am sorry you bought this book. If it was given to you as a gift, then technically I am not required—or even entitled—to apologize to you. My apology should go to the original purchaser and they, in turn, should say sorry. To be honest, though, I can’t be bothered with any of those rigid laws and rules anymore. I can see they are needed for diplomatic exchanges, and as a onetime exponent of the art of the international apology—the leading exponent, I suppose—I was constantly grateful that the Professor had gone to the bother of formulating all the laws in the first place. But they have their time and their place and this isn’t one of them.

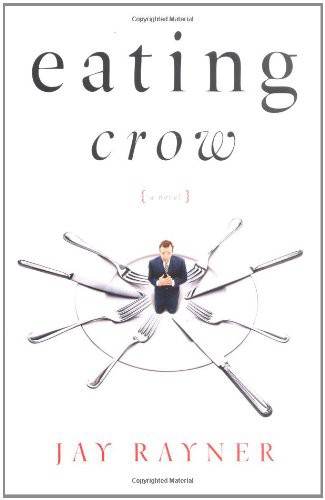

The point is, I’m sorry this book was bought. Somewhere along the line somebody has been conned by the smart-ass cover art which the art director obviously thought would set it apart from all the other guff on the bookshop shelves (and which, admittedly, did the trick, or it wouldn’t be in your hands now). Beautiful trees have been destroyed needlessly to make the paper. Then there’s the grievous waste of oil-based ink. And we mustn’t forget the obscenely large cash advance paid on this insidious doorstop which will, inevitably, result in the publisher having to spend its remaining money on banal, dead-certain bestsellers to the exclusion of anything new, interesting, or challenging. Finally, of course, there’s the waste of your time, should you be one of those people who insist upon finishing a book once they’ve started it, and I know there are a lot of you out there.

I admit—and under the Professor’s first law, I am required to admit—that I am not sorry about absolutely everything in this book. There’s some pretty good writing between pages 129 and 133. I like the descriptions of my father, which are honest, and I always will have a warm place in my heart for the tasting menu of chocolate dishes in chapter 29. It really was as good as I make it sound.

As for the rest of it, I think you probably get the idea by now. I’m sorry. I’m just so bloody sorry.

I

t starts with a phone call. I recognize the voice immediately, although not the tone. Usually this woman wants only to make me happy. Today she wants me to hate myself.

“Hestridge is dead.”

“What?”

“John Hestridge is dead and you killed him.”

“Hang on a second, Michelle—”

“You might as well have put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger.”

“How did he die?”

“Of course you want the details.”

“As I’m supposed to be responsible, naturally I want details. How did he die?”

A pause.

“Michelle, tell me how he died.”

There’s a gulp at the other end of the line, as though she is trying to swallow enough air for the task at hand; as if the usual draft could never be sufficient.

“He drank a bottle of whiskey and climbed into the large bread oven as it was heating up. Then he pulled the door shut.”

“It sounds like an accident to me, a drunken stunt that went wrong. I can’t see how I—”

“He left a note explaining himself and a copy of your review, taped to the outside of the oven.”

I thought I could detect a note of triumph in her voice. “I—”

“You killed him, Basset, as surely as if you’d pulled the trigger.”

There is a click and then the hiss of white noise. She has gone.

There is something you should know. As a child, lousy with invention, I imagined I was responsible for my father’s death. This was a few years before he actually died, and none of the compact dramas I devised ever matched the cruelty of the real thing, which closed him down slowly, an organ at a time. In my daydreams I was the oblivious child in the middle of the road as the truck thundered down upon me. Dad would be the one to push me to safety, only then to take the full force of the impact. I was the little boy who, reaching for a handhold, pulled the stockpot that always stood boiling upon the stove in our house off and over him in a fury of steam and fat as he stooped to tie my shoelace. I was the one he saved from the offshore currents; he was the one who was dragged away by them. And when, rushing home from school, I would find him alive, praying at the stove as he fed the stockpot, or at his desk, his huge, cardiganed back hiding its contents from view, there would be waves of relief, but something else too: a frisson of disappointment. I really did not want my father dead, but I did want to be interesting, and at eight or nine years old I assumed that grief, cruelly earned, would make me that.

You don’t need to be a shrink to understand that my father was the focus of my bereavement fantasies because I loved him. Even as a child I could see that. André Basset arrived in Britain in the late 1940s from a small town in the French-speaking part of Switzerland where, as he put it, nobody ever swore or farted. His relationship with his native country was sullen and uneasy. He never once returned there, but he made his living as an architect designing the Alpine chalets that Britain’s suburban nouveaux riches loved so much in the sixties and seventies: big, overhanging roofs sloping down to the ground like starched wimples, wood and faux rock front elevation, huge plate glass windows probably shielding an overengineered rubber plant. If you see one anywhere around London it was designed either by my dad or by a Swiss German from Zurich called Peltz whom Dad would only ever refer to, with a derisory snort, as “the little guy.” (They don’t have much time for each other, the Swiss French and the Swiss Germans; the only thing that unites them is contempt for the Swiss Italians.) It was as if, together in their competition, these two Swiss-émigré architects were rebuilding the country they had left behind, house by house.

My father never lost his French accent, although he did lose quite a lot of French vocabulary which he failed to replace completely with its English equivalent. Language was always a crapshoot in our house: he would “reserve” the car into parking spaces, we were constantly having to deal with things which were an unavoidable “fucked of life,” and my brother and I had to make sure that we used lots of “lovely soup” when we washed our hands. He was oblivious to these linguistic pratfalls, and when we small, giggling boys tried to adopt some of them as our family’s secret language, he was most insistent that we should not: “What do you mean wash your hands with soup? The word is

soup.

Speak English like I do.”

But he did fear that his foreignness could be an embarrassment to us. He tried to make it easier on my younger brother and me by insisting that his surname be passed on with a hardened, rather than silent, final

t

, so that when announcing it now, I always say “Basset, as in hound.” He then sullied our Anglo-Saxon credentials by insisting that I be named Marcel and my brother, Lucas, so that we sound like some desperate circus act: Marcel and Lucas, the Flying Basset Brothers. As a kid I hated my name, but it works now, at least in shortened form. Marc Basset is a good name, the kind people remember. It functions particularly well as a newspaper byline.

There was one language, however, in which André Basset was fluent, and that was food. Seventies Britain was fixed in a deathly monochrome of bad taste. It was a country so dismally impoverished that it considered Vesta’s range of instant Chinese meals exotic and regarded a tube of Spangles as a worthy substitute for dessert. In our house, though, everything was Technicolor. Even today my oldest friends tell me that our house always smelled of food, although what it really smelled of was the stockpot over which my dad fretted. He was forever topping it up and adding and sniffing and skimming and sipping and skimming again. When he had run out of ideas at his drawing board he would stand in front of the stove and stir. Most evenings he would take a few ladlefuls of whichever stock it happened to be—beef or chicken or, if possible, veal—and strain it into a pan. He would reduce it until he was content. And then at that moment, with the spoon poised at his lip, he would say solemnly, “We may begin.”

There were sauces with chunks of earthy morel to accompany steak, and with specks of black truffle for chicken. There were velvet sauces mounted with butter or spiked with cognac or sharpened with orange juice. He also cooked, from Provence, a dense bouillabaisse that was an assault course of fin and bone but which rewarded the effort with dramatic flavors. From Italy came great mounds of homemade silken pasta, and from the confused landscape of Mittel Europe, irresistible Strudels and tortes. He did these things to make us happy but also to gratify himself, for he loved to eat and it showed. Just as he built his houses, so he built himself, and me too. We were always bound to be big, my father and I, and while I would like to claim there was a genetic predisposition to these things, I know the stockpot had nothing to do with our DNA. We ate because it was part of who the Bassets were. I can legitimately blame my father’s genes for the painful reproach of my feet, with their shattered arches and curled, callused toes, those desperate failures of biology which have kept grinning podiatrists in fees since I was just a child, for he shared my symptoms. But I have always accepted that my size belonged under a different heading, the one marked “learned behavior.” When, in adolescence, sex raised its head and I began to suspect that my spectacular failures with girls might have something to do with the female softness of my thighs and the spread of my belly, it was an image of that rumbling stockpot that came to mind, and with it, my father leaning deep into the steam. I held it in contempt, but at the same time, I found the thought of it reassuring.

It was when my father stopped eating that we knew he was ill. The trips from his desk to the stove became fewer and fewer. The spoon was lifted to his lip less and less. I remember him in the autumn and winter of 1982, more asleep than awake and, when conscious, consulting with doctors. There was hushed talk, and later, after all the operations, the smell of stock in the house was replaced by the smell of disinfectant. He became a small man, and because he could not bear to waste the few trips he had the energy to make on visits to clothes shops, he slipped away inside his old ones until my mother began inexpertly to alter them. My father took on the appearance then of an old man stitched away inside a sack. He died in February 1983, shortly before my thirteenth birthday. He was forty-one years old.

Because of my earlier fantasies, I could not escape the feeling that by wishing him dead, I had made it happen. One night I told my mother this, my dear English mother who had been swept up by this belching mountain of a man and then deserted by him. She held me at arm’s length, a hand gripping each shoulder as if to stop herself from falling down, and said, “Marc Basset, you are never to blame. You can never be to blame. It is not your fault.” Then we both cried, and Luke came downstairs from his bed and joined in too and it was almost like being a family again.

The point of relating all this is that being accused of causing another man’s death plays badly with me. Me and death have a history, and mention of it makes me edgy. When I feel edgy I do what my father used to do when he couldn’t concentrate. I eat.

After Michelle’s phone call I went to my desk in the corner of the living room. I pulled open the Vice Drawer and dragged my fingertips slowly over its high-energy contents. It was well stocked, as it always is. There were a couple of thick bars of Valrhona Manjari, with over sixty percent cocoa solids the king of dark chocolates: intense, fruity, no acidic end, just lots of building flavor. I cracked off a couple of squares and then, for good measure, took another. There were also, from Calabria, some figs encased in dark chocolate and a few soft, dark chocolate truffles infused with tobacco, which I was testing for a friend who is a chocolatier. They have an almost chili heat that comes in slowly and grows, followed by a long finish, a bit like a big tannic red wine. I wasn’t yet entirely convinced by them. The flavorings seemed to fight the chocolate. But this was a serious moment so I took three, and the same number of the figs just to be sure. I dropped a square of the Manjari into my mouth, allowed it to melt slightly on my tongue, and then bit into it. Now I could think.

I hadn’t known John Hestridge but I did hate him. He was a man for his times and I could say nothing worse about anybody. There was, in the great cities of the Western world at the beginning of the twenty-first century, an appetite for eating that had nothing to do with hunger. It was people like John Hestridge who fed upon those appetites. They created rooms that were uncomfortable and served nonsensical food in them at nonsensical prices. And yet still people came to sit in these rooms and eat this food and they liked themselves for doing so. It led them to believe that at this particular moment, they were in the right place. This drove me insane. But what really broke me up about Hestridge was that he couldn’t cook. By his choice of profession he ensured that animals died in vain. He destroyed fish. His sauces were too thick or too thin or just tasteless. His starters were too heavy, his desserts flimsy and insubstantial.

With my free hand I nudged my mouse so that the computer awoke from its slumber. I took another piece of chocolate and pulled up the review I had written of the new restaurant, Hestridge at 500. It had been published by my newspaper two days before.

Desperately poor cooking is not yet an offense punishable by execution, not even in some of the more enthusiastic states of the Southern US. But if it were, you could be certain that John Hestridge would be hanging out right now on death row, counting the days. It is only to be hoped that should such justice ever catch up with him, he would have the good sense not to order any of his own dishes as his last meal. No one deserves to leave the planet with that in their stomachs, not even John Hestridge.

And so on.

Not kind, is it? Funny, in a diverting Sunday morning sort of way, but definitely not nice. Still, I wasn’t being paid to be nice. I really did hate the food and I had a responsibility to say so. That was what my readers expected of me, wanted from me, even, and I was happy to deliver. I hadn’t before dwelt too much on what effect my words might have on the people they were about.

I needed a diversion so I flicked on the television to catch the top stories on the midmorning news. First story: The collapse of the Slavery Reparations Conference in Alabama. Soundbite from Lewis Jeffries III, African-American delegation leader, with a deftly sorrowful speech (“It is for the children of tomorrow that we seek justice, not just for the children of yesteryear”), then a sad nod of his graying head. I found myself admiring the hokey cadence of “yesteryear.” Second story: Separatist rebels in region on Russian-Georgian border issue ransom demand for release of American, Canadian, and British aid workers they are holding. Third story: Random, tragic death of entire family in Lincolnshire house fire.

It occurred to me immediately that the third slot was going begging. Journalistic instinct told me that once we’d had twenty-four hours of news cycles, sifting through the ashes, interrogating witnesses and safety experts, something else would be needed to replace the Lincolnshire fire story and a dead chef might well be just the thing. I wasn’t exactly sure how they’d spin it, but if Michelle Grey was half the PR woman I thought she was, she’d be trying to get her client airtime right now, whether he was dead or not. It also occurred to me, in the shameless way these things do, that such a story could be exceptionally useful to my career.

The phone rang but I didn’t pick it up. I muted the television and turned to watch the answering machine. The beeper whined and then a familiar voice broke through: