Eclipse (21 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clee

The first of these races, which came to be known as the Classics, was the St Leger. In 1776, a group of sportsmen subscribed to a new sweepstakes â a relatively recent innovation, in which several owners advanced entry fees that formed the prize money â at Doncaster. The race was over two miles (later reduced to its current distance of an extended one mile, six furlongs), and it was won by Lord Rockingham's Allabaculia.

103

In 1778, the sportsmen voted to name their race after one of their number, General Anthony St Leger, an Irish-born, Eton and Cambridge-educated former MP who bred and raced horses from the nearby Park Hill estate.

The catalyst for the next two Classics was another Eton and

Cambridge man. Edward Smith-Stanley, the 12th Earl of Derby, began his association with Epsom in 1773, when at the age of twenty-one he took over the lease of a nearby house called The Oaks. A year later, he married Lady Elizabeth Hamilton. The wedding was grand. General John Burgoyne, who had owned the property previously and who three years later was to surrender to American forces at Saratoga, played host and wrote a masque,

The Maid of the Oaks

, for the occasion; David Garrick, the actor and impresario, stage-managed the drama; Robert Adam, the great architect, designed the dance pavilion. But despite this splendid inauguration, and the arrivals of two daughters and a son, the marriage foundered. While playing cricket at The Oaks, Lady Derby met the Duke of Dorset, fell in love, and ran off with him. Lord Derby declined to divorce her, so preventing her from marrying the Duke, but also preventing himself from marrying the woman he loved, the actress Elizabeth âNellie' Farren. Lady Derby's death in 1797 cleared the way. This second union was much happier, even though Lord Derby's new bride did draw the line, the historian Roger Mortimer wrote, âat cock-fights staged in her drawing room'.

In other respects, Derby was a jovial, convivial figure. He hosted regular house parties, and at one of them the company agreed to establish on nearby Epsom Downs a new race, over a distance of a mile and a half, for three-year-old fillies. In tribute to the hospitality that brought it about, they named the race the Oaks. It was a sweepstakes, and the first running, in 1779, attracted seventeen subscribers contributing fifty guineas each to the prize fund, with twelve fillies eventually going to post. One of them, a daughter of Herod called Bridget, was Derby's; she was the 5-2 favourite, and she won. Down the field was an Eclipse filly with the bare name Sister of Pot8os. She was owned by Dennis O'Kelly.

Reconvening at The Oaks, Derby and his guests agreed that their fillies' race had been a great success, and that they should supplement it with another new sweepstakes, this time for both colts and fillies and over a mile, the following year. But what to call the race? Sir Charles Bunbury was among the party, and he, intent on encouraging speedier Thoroughbreds, had been a great promoter of these shorter races, for younger horses, carrying lighter weights. Perhaps the race should be named after him? And so we come to another racing legend: Bunbury and Derby competed for the honour by tossing a coin, and Derby won.

104

Had Bunbury called the toss correctly, we assume, the great race would have been named the Bunbury; the âRun for the Roses' at Churchill Downs would be the Kentucky Bunbury; a football match between Arsenal and Tottenham would be a North London bunbury; and motor cars would crash into one another in demolition bunburys. As it is, we remember Sir Charles with the Bunbury Cup, a seven-furlong handicap at the Newmarket July meeting.

105

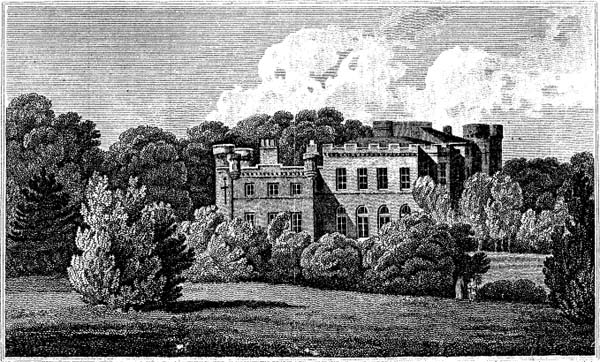

Lord Derby's house The Oaks, after which the classic race for fillies was named, and where, reputedly, Derby and Charles Bunbury agreed the naming of the Derby Stakes on the toss of a coin.

A year later, on 4 May 1780, Bunbury gained compensation when his colt Diomed (6-4 favourite) became the first winner of the Derby Stakes. Second was Dennis O'Kelly's Boudrow (4-1), by Eclipse. The nine competitors raced over the last mile of the course that Eclipse had graced eleven years earlier. This race was even more popular than the Oaks, attracting thirty-six subscribers who each contributed fifty guineas to the prize fund, Bunbury's winning share of which was 1, 150 guineas.

Diomed, by a son of Herod called Florizel, was not at first a shining advertisement for the Derby Stakes. His subsequent racing record was mixed, and his stud career was so undistinguished that

by 1798, when he was twenty-one years old, he was commanding a fee of only two guineas for each mare he covered. Bunbury gave up on him, and sold him to America. As the horse crossed the Atlantic, so did a message from James Weatherby's secretary: âMr Weatherby recommends you strongly to avoid putting any mares to [Diomed]; for he has had fine mares to him here, and never produced anything good.' Diomed also had a reputation for firing blanks, semen-wise.

However, just as there was a wonderful alchemy when Arab stallions met English mares on English soil, so was there when Diomed met American mares in Virginia. The stallion would emerge from his stable at a gallop, and set about his procreative task with the enthusiasm and vigour of a horse half his age.

106

Diomed sired numerous champions, right up until his thirtieth year, by which time his covering fee was $50. He died at thirtyone. âWithout Diomed, ' a US historian observed, âthe most brilliant pages of our Turf story could never have been written.' Four generations down his male line came Lexington, a stallion who by the end of the nineteenth century was to saturate the pedigrees of the best American racehorses â and who created a headache for the compilers of the

General Stud Book

, because, like Copenhagen, he had dubious ancestry on his dam's side.

Several of Lord Derby's guests, and particularly Sir Charles Bunbury, would have been dismayed if the rogue Dennis O'Kelly had won the first running of the Derby Stakes. But Dennis had come close, and in 1781 he won the second running, with Young Eclipse. âJontlemen, ' he told the Munday's coffee house crowd in the weeks before the race, âthis horse is a racer if ever there was one. 'Alas, the Derby turned out to be Young Eclipse's finest hour, as it had been Diomed's; and Young Eclipse was not a successful stallion. Describing the horse as ânot a bit too honest', a writer â probably John Lawrence â noted in

The Sporting Magazine

,

âO'Kelly on first training this horse for the Derby, which he won, was certainly deceived, having flattered himself that fortune had favoured him with another Eclipse! Vain expectation, that two such phenomena should appear together in the world! Between Flying Childers and Eclipse, there was an interval of between 40 and 50 years, and we shall be in high luck, indeed, if we can produce a third to those â what a trio! â within 50 years of the latter.'

The writer went on to note that it was not always possible to take the inconsistent form of Dennis's horses at face value: ârace-horses, more particularly in hands such as those of Dennis O'Kelly, are extremely apt to run according to the immediate pecuniary interests of their proprietors'. If the owner wanted to lay against a horse, the horse was apt to run slowly; next time, with the owner's money down at a bigger price, the horse would show miraculous improvement. Such practices, or at least suspicions of them, have not gone away.

Dennis's horses were probably all trying in the Derby, though. It was too valuable a race to mess about in. He had the Derby second again in 1783, when Dungannon, later to stand at his stud, lost out to Saltram, also by Eclipse; and he won for the second time the following year, with another son of Eclipse called Sergeant.

107

Lord Derby triumphed in his own race in 1787. He and Lady Elizabeth were still married, but living apart, and he and Nellie Farren were conducting a relationship of apparently irreproachable propriety. âThe attachment, ' James Boswell wrote, âis as fine as anything I have ever seen: truly virtuous admiration on his part, respect on hers.' One of Nellie's most celebrated roles was Lady Teazle in Sheridan's play

The School for Scandal

. Lord

Derby ran a filly called Lady Teazle in the 1784 Oaks, finishing second; three years later, Sir Peter Teazle, his only Derby winner, gave Derby's virtuous admiration an enduring symbol in the sporting record books. He later turned down a bid for the colt of 500 guineas from, according to

The Times

, the Duke of Bedford and Dennis O'Kelly.

108

Sir Charles Bunbury was to win the Derby twice more. There was Smolensko, whose jockey was so meanly rewarded, and before that, in 1801, a filly called Eleanor. Some time before the 1801 race, Bunbury's trainer Cox fell mortally ill. Close to death, with a parson standing by, Cox indicated that he had something to say. The parson bent low; Cox breathed in his ear, âDepend upon it â that Eleanor is the hell of a mare.' He was right: Eleanor beat the colts in the Derby, and a few days later won the Oaks as well. She is one of only four fillies â âfilly' is a more usual term than âmare' to describe a horse of three â to achieve the double.

109

The Derby was not yet the most important race in the calendar, but it was getting there. The founding in 1809 of the 2, 000 Guineas (one mile, for three-year-old colts and fillies) and in 1814 of the 1, 000 Guineas (one mile, for three-year-old fillies) facilitated the rise in prestige, because these races became preludes to the Derby and the Oaks, which in turn led to the St Leger. The five races became the English Classics, the prizes that all owners dreamed of winning, and that were the highest goals of the breeding industry. By 1850, the Derby was stopping the nation: Parliament adjourned during the week of the race. âWe declare Epsom Downs on Derby Day to be the most astonishing, the most

varied, the most picturesque and the most glorious spectacle that ever was, or ever can be, under any circumstances, visible to mortal eyes, ' the

Illustrated London News

asserted.

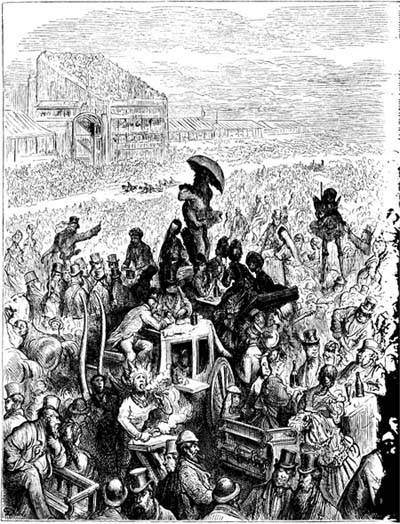

The Derby â At Lunch

by Gustave Doré (1872).âThe Derby is emphatically, all England's day, ' wrote Blanchard Jerrold in his accompanying text.

In the middle of the twentieth century, the owner and breeder Federico Tesio â who bred the champion Nearco â could say, âThe Thoroughbred racehorse exists because its selection has depended not on experts, technicians or zoologists, but one piece of wood: the winning post of the Epsom Derby.' And it was this piece of wood that reinforced Eclipse's dominant role in racing history. Five of the ten Derby winners in the 1850s, when the

Illustrated London News

hailed the glorious spectacle, were from the Eclipse male line. By the first decade of the twentieth century, the figure had risen to nine out of ten. In the past fifty years, all but three Epsom Derby winners have been Eclipse's male-line descendants. The history of racing's greatest race is a tribute to the sport's greatest horse.

95

By Phil Bull, the founder of the ratings organization Timeform.

96

Having argued that horseracing reflects society, I must concede that sometimes the adaptation to wider influences is sluggish. The Jockey Club, a self-selecting body, ran British racing, the tenth largest industry in the country, until 1993, when it transferred its administrative responsibilities to the British Horseracing Board. In 2006, the JC handed over the policing of the sport to the Horseracing Regulatory Authority. A year later, the BHB and HRA merged, to form the British Horseracing Authority. Now, the JC concentrates on the administration of its racecourses and other estates.

97

This was the Escape Affair. See chapter 17.

98

Eclipse's pedigree is examined in Appendix 2.

99

âAny horse claiming admission to the

General Stud Book

should be able: 1.To be traced in all points of its pedigree to strains already appearing in pedigrees in earlier volumes of the

General Stud Book

, those strains to be designated “thoroughbred”. Or: 2.To prove satisfactorily eight “thoroughbred” crosses consecutively including the cross of which it is the progeny and to show such performances on the Turf in all sections of its pedigree as to warrant its assimilation with “thoroughbreds”.'