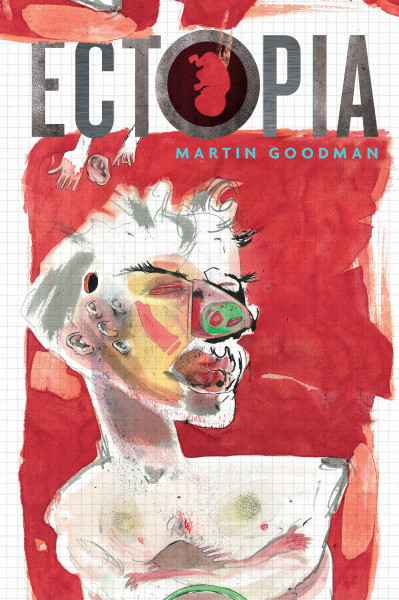

Ectopia

Authors: Martin Goodman

Â

Martin Goodman's first novel was shortlisted for the Whitbread Prize, and his most recent biography won 1st Prize, Basis of Medicine in the BMA Book Awards 2008. Other nonfiction writings explore the extremes of the spiritual life: shamanism, sacred mountains, hallucinogens, and self-proclaimed goddesses. Other fiction focuses on the aftermath of wars. A BBC New Generation Thinker for 2012-13, he is Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Hull, and Director of the Philip Larkin Centre for Poetry and Creative Writing.

Â

Also by Martin Goodman

Fiction:

Look Who's Watching

Slippery When Wet

On Bended Knees

Â

Nonfiction:

Suffer & Survive: The Extreme Life of Dr J.S. Haldane

On Sacred Mountains

I Was Carlos Castaneda

In Search of the Divine Mother

Â

Â

Â

Published by Barbican Press in 2013

Copyright © Martin Goodman 2013

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention

No reproduction without permission

All rights reserved

The right of Martin Goodman to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

First published in Great Britain as a paperback original by

Barbican Press

1 Ashenden Road, London E5 0DP

www.barbicanpress.com

A CIP catalogue for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-956336422

Typeset in 11.75/15.5pt Garamond by Mike Gower

Cover image: âMalchus' Ear Healed' by Ian Pollock

Cover Design by Jason Anscomb of Rawshock Design

Printed and bound by Lightning Source UK Ltd., Milton Keynes

James

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Bender â

Clock Zero

Â

0.00

Others have sisters. Older sisters. My sister's the one they all want though. She's older than me by a couple of hours. She's me with a slit and tits. We boys sit in a semi-ring of chairs on education-and-reporting night. The light from the vidscreen makes our faces shine like we've rubbed in radiation. Best would be to get a ladder and perch behind the vidscreen. I could look down on em. See their faces pale with longing. Pretend they're looking up at me.

I don't though. I join in.

A film's just started. Teensquad puts up with the beginning coz they know how it ends.

It's my film. I made it a year and a bit ago as my entry piece for teensquad. We have to make a film about our family home to show the truth behind family values. That's the official shitline. Statesquad preaches crap like that and we all go numb and blank. We don't run the streets to keep our homes safe. We run the streets to get away from home. We keep the streets clean coz that's where we live. Home's as full of shit as ever.

I call my film Fuck All, coz that's what happens at home. I hate watching it but it's teensquad's favorite. They outvote me every time and set it running.

The film starts on the street facing our fence then goes in through the gate of the house. It's a basic film. I kept the camera running and walked till the five minutes were up.

The gate opens and there's Dad. He made us call him Pop when we were little. I'm Steven Sickel. He was Alan Sickel. Pop Sickel. Popsicle. It was a joke. A pet name. You give names like that to things you love. We grew up and let the name drop. I call him Dad when I call him anything, though it's a lie. That old father son thing's a dead concept. If he's like a Popsicle at all, he's like the stick that runs up through its center.

Dad's in the garden. He's stripped himself down to a pair of baggy shorts. What's on show is a freak. His body's white coz he protects it from the sun, with baggy pants and shirts with sleeves that hang over his wrists and hats with peaks.

Today he's showing off for the camera. He says he's got a six-pack and displays it indoors when he's drunk but what we see are ribs. He's tall, and walks in that loose way skeletons walk in vidgames, the limbs hanging or swinging. His bones should rattle but they don't. He can go about dead silent, letting breath hiss through his teeth sometimes to show he's still living. Grey hairs curl on his white chest, but the hair on his head is shaved with some grey fuzz showing like his head's out of focus. His head's a skull and the skull's grinning. He's wearing round steel spectacles, and boots on his feet. He waves an axe in the air. The muscle flexes in his right arm. His muscles are fine but they don't suit him. He thinks he's lean and fit but he's sick. The muscles don't impress me. I think of em as tumors. He's about to chop down our apple tree.

Dad made money in lumber. He worked in the timber industry, before trees were protected and when they still grew. A statesquad inspector came and drew the white cross on our tree's trunk. It's officially dead. Dad can chop it down. He's got a chainsaw but he's saving all his fuel for some big gig so he raises his old axe. It's his big moment, the last strike of the lumber man, and he wants it caught on film.

Well fuck him. Fuck that. I turn the camera away.

This isn't his film. It's mine.

I pan the garden. It was still a garden in the film, not the mantrap Dad's been making of it since. Everything's dead. Mom stood by the fence once long ago and said the other man's grass is always greener. It was an old saying. It maybe made sense when grass was green and didn't powder under your feet. The grass is brown, flowers and leaves brittle on dry earth, roses in the shape of the sticks and thorns Mom pruned em to when they died. It was her garden. She pressed its last flower, a yellow weed, between the pages of a book, and hasn't come outdoors much since. In the film I walk the camera to the back garden and her silhouette blots the kitchen window.

I finish the garden and point the camera up at the house. It's a red brick nothing house, dead ivy stuck to the walls, a door and a window downstairs, two windows upstairs, one of em mine and my brother Paul's, the other Mom and Dad's.

Back round the house and in through the front door. We turn right into the front room. Paul's plugged into the console in the corner and doesn't look up. He's not changed much in the last year. His sweat stinks but that doesn't show and if he stood up you could see he's grown, but he stares into the screen as intense as ever.

Mom's in the kitchen with her hands in soapy water. Maybe she thinks it shrinks em. It's funny to see her just a year ago. You wouldn't think she could grow bigger than she was then but she has. She still has a neck in the film. She can turn her head round without turning her whole body. Her walnut mouth is open, her lips forming words as a song comes out. She turns full round when she sees the camera, so she can give a real performance. She was a singer before the swelling started. She stood by a piano and sang songs. It's one of these nonsense songs she's singing now. She says they're in German but who knows. She makes things up.

I don't wait for her to finish. There's no soundtrack in any case, just a pulsing beat someone's added in the editing. I go back through the front room, into the hall, and start up the stairs.

Teensquad stirs. Hands slip down the fronts of their shorts. It's a group thing. A group jerk-off. I don't join in. I don't pretend. I don't like what's coming though I don't mind sneaking glances and the smell of come's a turn-on.

Here's my memory of making the film. Karen's sitting on the floor of her bedroom when I walk in. It's before she got her treadmill, when she was into yoga, so she's dressed in silver spandex and lying on her back. Her arms are to her sides, and her right foot is pressed against her left thigh. Her ginger hair's hanging over her right eye but she opens her left one, stares at me, and tells me to fuck off. I back away slowly. End of movie.

On the vidscreen things are different. Her fifteen year old breasts expand and the spandex melts away. A broad and naked body grows on top of her slight and dressed one. The breasts are so big they flop. The triangle of pubes between her legs isn't ginger like it is but a bush of black. She lifts a finger with bright red nails and beckons the camera closer. We draw near and she licks her finger then slides it down her naked body.

It's a digital remastering. Some image from pornbank's been cloned onto Karen's body. The work's crude. Teensquad wants Karen coz she's the youngest girl on the planet, but they've switched that fifteen-year-old body for this plump and heaving twenty-five year old porn has-been. She fingers herself, they jerk off, everybody comes.

Fuck All's a hit. It's a film about my life and I'm not even in it.

I turn the lights back on while the rest are wiping down, and head out for a solo run.

Â

No-one's banned solo running at night. You do it if you're crazy.

I get crazy sometimes. The air's still but the sun's gone and I can run up a breeze. Go fast enough and runsweat dries off my face.

Old couples grunt. Baby boys wail. Teenagers scream their way out of nightmares. Sounds from houses I pass tear me up sometimes. You can't run from being an empath but you can smudge out the sounds. I set the headphones to runpulse and turn up the volume. My strides grow longer and I reach the edge of town.

Town is lit by solar strips. Orange arcs of light leak out at night. Beyond the town, beyond the fencing, Cromozone blazes.

I take off the headset to hear it. The place has its own pulse. They say they run generators but generators roar and this sound is soft like a heartbeat. The place glows, from the sheds at the outskirts to the towers at the center. It's a halogen glow that gathers in a dome as white as the moon.

This voicecard came from a statesquad unit inside Cromozone. The card came with the teensquad rations. They've made me the teensquad scribe. What happens in teensquad, what happens in my days and nights and thoughts and dreams, anything I want to say about my life, I can say into this card. It's secret, they tell me. The card is encrypted and I must make my unique code. Whatever I write, only I can read. I am scribe and keeper of our teensquad records.

That's a shitline, Cromozone. You're listening to me now as I sit right here and watch you glow. Bet you are. Listen on. I've got no secrets. Secrets are treasures or secrets are guilt.

I've got no treasures. The world gives me nothing.

I've got no guilt. I'm young. It wasn't me who fucked up the planet. Nothing I can do can make things any worse.

I'm scribing for the future. There is no future. So scribing's pointless. Life's pointless.

So scribing is the meaning of life.

Reading this is the most redundant activity in the world.

You'd be better off doing what I'm going to do now.

Run.

Karen's Book

âMom' â a competition essay by Karen Sickel (age 16), to be judged by the Council of Women

Â

Mom sprogged me and I was a girl so that was nice, then some hours later she sprogged Steven and he was a boy so that was terrific and Dad got drunk on whisky and lost consciousness and when he came round good news was bad news and he wasn't a proud father any more. It didn't last long for him. Other boys got born between me and my twin Steven because Steven's like that, he sees the future and doesn't want any part in it so he took his time coming, but no girl in the world was born after me. I'm the last girl in the world. That makes me a statistic and a freak. It's freakish to be normal in a world that's gone sick. It's sick to be a statistic. I don't like the world but I do like my Mom. She's mad but that's normal and at least she's different. She's mad in her own way.

I don't think Mom wanted kids, at least not with Dad. They were just husband and wife, bitch and buck before that, him telling her she was loud and she telling him he was useless, they had their understanding and they lived their disappointment and that was OK because that's what people did but they weren't yet Mom and Dad. The universe hadn't linked them in that weird unsexy way. Then we two twins came along. We marked triumph and disaster, the beginning and the end.

“What did you ever see in him?” I asked when I was about ten and Mom was still coherent.

“Your Dad loved wood,” Mom said. “Other timber merchants don't. He was hands-on, never bought off the Net. We went to furniture outlets together and he stroked wardrobes and chairs like he loved them. He pulled tablecloths off tables when we ate in fancy restaurants, so we could share the bare surface. He counted the knots in spruce ceilings like he was counting stars. The feel of oak made him teary with nostalgia, the grain in walnut made him poetic, mahogany and teak made him speechless though I don't k

now why. He was passionate about wood. It seemed a bit artistic. I thought he was a homemaker. I thought he was a safe bet.” She blinked a bit but no tears came. “I wasn't all wrong,” she said. “The house isn't stuffed with cheap plastic. We've got nice things.”

If I got to run like Steven runs I'd see stuff like ours, wooden lamps and wooden frames and bedsteads and cabinets made of wood, and stuffing puffing from sofa cushions like it does from ours but the sofa's got arms of ancient elm so we're meant to love it nor chuck it out like normal people do, so the sides of the streets are lined with the stuff that clutters the inside of our house. Mom's not a homemaker. Dad's a collector. He gets the run of the house.

Mom doesn't do homemaker and she doesn't really do Mom. Motherhood started to stink before they tossed out my placenta. People bred for the future, and now there's no future and babies are drains.

Mom was a diva. She's given up now but once upon a time she played Mom as a stage role. When Steven and me were tucked up at night she placed a chair, a wooden chair, between our beds to face us both. A candle on the hickory bedside table cast shadows up from her high cheekbones to darken her eyes and soften the red of her lips. She had a face then like mine is now, with a shape to it that wasn't just a balloon, but older than mine and painted with makeup. Mom dressed for her lullabies in a long white gown and lit the candle for effect. She sang us Brahms's lullaby, which she called

Wiegenlied

.

Guten Abend, gut Nacht, mit Rosen bedacht,

Guten Abend, gut Nacht, von Englein bewacht

The door slammed back against the wall and Dad came in.

“I won't have that kind of language in my house!” he said.

That's my first memory of Dad and Mom together. He didn't shout. He just delivered every syllable like a slap round the face. It frightened us. Mom held a silence, just long enough for our fear of Dad to register, then she spoke.

“You remember who pays for this house,” she said. “And you remember what pays for it.”

We were little and didn't know what they meant or what language was or that Dad was a xenophobic bastard who didn't like German or anything foreign and houses had to be paid for. We knew Dad had frightened us but Mom spoke and that dealt with him. Dad withdrew and we were safe again. We were a family split into two camps. Mom opened her throat wide like the new gulf between Dad and us and her lullaby bloomed into a concert.

Our little brother Paul wasn't family. He was his own thing, a blob of baby. We played with him. We picked him up and turned him around and built him mazes of furniture for him to crawl through and find his own way out. Mom never noticed him much. He was like a stain you got used to. Dad dressed him and bathed him and put him to sleep in his cot and picked him out again. His first word was dada so Dad had someone that talked to him at last. He took Paul's hand and they walked around together, Dad calling him my little mate and looking at us sideways and them giggling like they were in on the joke and the joke was us. They were sad but it was OK because Steven had me and I had him and Mom was in a world of music and herself. When Mom was gone with her bedtime lullaby Steven or me climbed down, crossed the space between the beds, climbed up, and we slept not so much together as around each other.

In the mornings we woke and parted but that wasn't enough for Dad. It wasn't right, he said, a girl and a boy sharing a room like that, it wasn't healthy to be so close. He dragged Steven's bed from our room and put him with Paul in a separate place. I've not slept since. I just coast the night, hearing sounds.

Planes used to fly over our house and their roar was like being with Mom. She moves around slowly but carries the threat of sonic boom. Our house is worth lots because it's a 3 bed detached but Mom needs a stage not a domestic box. We saw her on the stage once, Steven and me. She was dressed in stripes of vertical rainbow and sang more Brahms, a requiem, and the orchestra massed and stroked and struck and blew away like they were playing up some wild ocean yet Mom's voice, the voice of one single woman, just fed on that sound and rose above them all like a high tidal wave.

The hall was packed and silent when the singers and players finished, then everyone rose and shouted and clapped. We stood on our seats and watched Mom gather bouquets into her arms. She stepped away from the orchestra, from the conductor, away from the other singers, and walked into the wings. It was her last concert. Her performance was glorious and fatal. She had risen high on one line of song and simply kept on rising. The orchestra went quiet as she left them behind and they waited for her to return. They tell me a singer can't do that, that it's not allowed. Well she can and she did and it was amazing.

She sang to a program in our front room, sometimes with orchestras but she liked the piano best, the piano sound coming from speakers mounted in special wooden boxes. I worked the controls of the computer, choosing Alfred Brendel or Gerald Moore or Michiko Hichita, always one of those greats from the past, and set Mom's voice to be the dominant factor. As she stretched a line to the close of her breath the pianist would pause in awe and respect. The program attuned to Mom's solo flights and then found the right mix of recorded piano notes and sent waves of cadenzas to chase after her. Mom sang from the heart of the music, not from the score.

Mom's famous in the world beyond our street, and people pay to download her voice. That's what buys the life in our house, the boxes of food that come to the door, the oak-barreled whisky down in Dad's cellar and his illusion of earning a decent wage. I play her songs still. Mom goes solo now, so deep into the land of invention and loss that no computer accompaniment can ever follow her again, but her recorded voice is like a neural link to the power that still floods inside her.

Mom's everything and nothing all at once. She's a raft bobbing lost in an ocean and she's the ocean too. She's being lost and being found both at the same time. It starts off safe when she holds you in her arms then it feels like sinking and drowning. Her womb held me and Steven while she sang us into life. Then the world went sour. The songs drew on old hopes then lost their way.

What do I get from Mom?

She taught me German. She gave me music to analyze and appreciate and she's made me want to keep control. Mom's filled with power and I am too but I try to keep the surge inside.