Effigies

Effigies

Copyright © 2006 by Mary Anna Evans

First Edition 2006

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2006929246

ISBN 10: 1-59058-342-6 Hardcover

ISBN 13: 978-1-59058-342-5 Hardcover

ISBN 13: 978-1-61595-232-8 Epub

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

The people and events described or depicted in this novel are fictitious and any resemblance to actual incidents or individuals is unintended and coincidental.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

For the Americans who were here first…

I’d like to thank everyone who reviewed

Effigies

in manuscript form: Michael Garmon, Erin Hinnant, Rachel Garmon, David Evans, Deborah Boykin, Rae Vaughn, Lillian Sellers, Robert Connolly, David Reiser, Suzanne Quin, Carl Quin, Leonard Beeghley, Mary Anna Hovey, Kelly Bergdoll, Bruce Bergdoll, Diane Howard, and Jerry Steinberg.

I’d also like to thank these folks for their expertise in an impressive variety of subjects, including archaeology, Choctaw folklore and history, Neshoba County geology, library research, and the mounds and cave of Nanih Waiya: Elizabeth Slater, Robert Connolly, Sam Brookes, Kenneth Carleton, James House, Tom Mould, the faculty and staff of Brentwood School, Maurice Calistro, Greg Cheatham, and Cheryl Breckenridge.

And, as always, my agent Anne Hawkins, and the hardworking crew at Poisoned Pen Press: Barbara Peters, Rob Rosenwald, Marilyn Pizzo, Jessica Tribble, Monty Montee, Nan Beams, and Geetha Perera.

Nanih Waiya, the great mother mound of the Choctaw people, has guarded the source of the Pearl River for millennia. The Muskogee people were birthed from her earthen body first, but they left her. The Cherokee and the Chickasaw are her children, too. They lagged behind for a time, drying themselves on their mother’s flanks, but the day of leaving came for them. Neither the Cherokee nor the Chickasaw ever caught up with the Muskogee, who were so careless with fire that they obliterated their own trail. Brothers and sisters were parted, and they never met again.

The Choctaw, like most lastborn children, are bound tightly at the heart to their mother. They live in the shadow of Nanih Waiya still. Invaders have tried to rip them away. Disease has stalked them. The mighty Army of the United States of America has hauled them bodily to places they did not want to go. But the trees grow thick around Nanih Waiya, and a remnant of the Choctaw has always found a place to hide there. How have they outwitted forces so implacable and strong?

Thursday

The eve of the Neshoba County Fair, Mississippi’s Giant House Party

Faye Longchamp had work to do, but it could wait. A tremendous backlog of unfinished tasks seemed to be her lot in life. Taking a weekday afternoon to immerse herself in history and religion simultaneously seemed like an efficient way to use her time. Granted, it was someone else’s religion, but Faye had never been too finicky about that kind of thing.

Joe, on the other hand, had a direct connection to the silent mound of dirt beneath their feet. His Creek ancestors believed that their history began here at Nanih Waiya, the Mother Mound. Or maybe in a cave under a natural hill somewhere across the creek. The issue was murky, as spiritual issues tend to be.

Faye considered Nanih Waiya, constructed at about the time Christ walked the earth, to be a most impressive perch. She and Joe sat atop it, forty feet above the natural ground level, surveying Nanih Waiya Creek and a lush forest and a very ordinary pasture full of cattle grazing just outside the fence surrounding the great mound. She had noticed a sour, familiar smell as she climbed the stairs sunk into the old mound, but couldn’t quite put her finger on its source. The creek’s banks were brimming, so she thought perhaps she was sniffing the musty, peaty smell of a swamp at high water. Either that, or somebody needed to empty the garbage bins at the state park across the road.

Only when her head cleared the top of the mound and she could see the grassy open area beyond did she put a name to the odor. Cow manure.

Did it bother Joe to see this sacred place shorn of its trees and planted in pasture grass? He didn’t look perturbed. Faye thought about cows for awhile. They fed their calves out of their own bodies, then fed the land with their manure. Eventually, they fed the land with themselves. Maybe the Mother Mound liked having cows around.

Not being nearly as spiritual as Joe, she figured her revelation about the holiness of cows was the deepest thought she was likely to have that afternoon.

“Let’s go, Joe. If we hustle, we can get a look at our work site this afternoon. Dr. Mailer said he’d be there to meet everybody as they rolled into town.”

Joe Wolf Mantooth raked a farewell glance over a landscape that had been held holy for centuries. Millennia, in fact. He could see a far distance from up here on top of Nanih Waiya, and he was glad to get the chance to visit the Mother Mound. The afternoon light was already a little softer than it had been at noon, and he knew the quiet summer air would be even quieter soon, as sunset approached.

Perhaps Joe’s senses were sharper than most men’s. Or perhaps Nature revealed herself more fully to him simply because he paid attention.

As he followed Faye down the mound’s flank, he gave one last look at the grassy field and the fecund swamp and the broad sky and, behind him, the towering mound. Was this spot more sacred than the glass-clear Gulf waters around the island home he shared with Faye? More God-touched than the cool, green Appalachians, or the familiar expanses of his native Oklahoma? All those places seemed holy to him. He saw no difference.

It never occurred to Joe that perhaps the holiness lay in a man’s appreciation of Nature’s gifts. Perhaps those places were more sacred simply because he’d been there.

The route from Nanih Waiya to their worksite had led Faye and Joe through a landscape of farmland and pastures and piney woods, without the necessity of passing through Philadelphia, the only town of any size in Neshoba County, Mississippi. Or in most of the surrounding counties, for that matter. Not being a fan of city living, Faye didn’t mind.

She liked the warm and fertile look of the place. She would have preferred to be at home in Florida, but she wanted an education and she needed to earn a living. Joyeuse Island, with its booming population of precisely two, didn’t offer much in the way of opportunity on either count, so she was happy enough for the opportunity to spend her summer here while earning graduate credit and money, too.

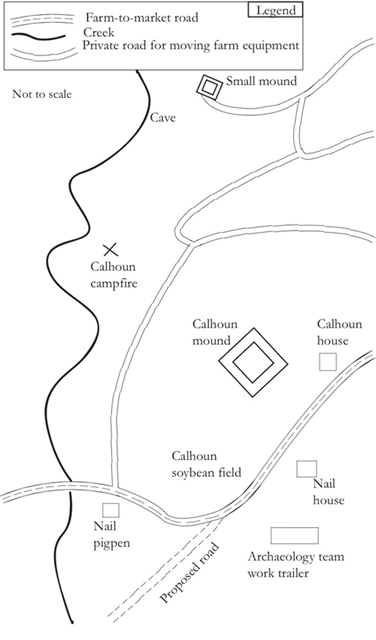

The map in Joe’s hands took them directly to a neat brick farmhouse that looked exactly as Faye’s boss had described it. A cluster of people milling around in the field out back looked a great deal like archaeologists. Their worn clothing had the requisite ground-in dirt in all the right places, and their faces were tan beneath hats that provided some solar protection, but not enough. It seemed that Faye had found her co-workers.

As she and Joe approached, she caught snatches of a conversation that sounded a lot more animated and cordial than it looked. An outsider would have interpreted the scientists’ lack of eye contact as unfriendliness, but Faye knew better. These people, out of long habit, rarely lifted their glance from the ground—not when they were standing in a known occupation site, where the soil was peppered with fascinating stuff. The young archaeologist who had found the site thought it might date to the Middle Woodland period, which could make it as old as Nanih Waiya herself.

Faye recognized a few faces from school. Dr. Sid Mailer, the principal investigator and her former lithics professor, stood, as he always did, in the center of a knot of his graduate students. Not for the first time, she missed her mentor, Dr. Magda Stockard, who might have directed this project if she hadn’t been recovering from the difficult delivery of her first child. Faye liked Dr. Mailer, but she wished she could work for Magda again.

A tall, sunburnt man in his late forties, Dr. Mailer’s prematurely white hair made him stand out in any crowd. Bodie Steele, a freckle-faced country boy who might someday take Dr. Mailer’s place as a leading expert on Middle Woodland lithics, hung back until Faye flashed him a quick smile. He responded with a nod and a small smile of his own. Toneisha MacGill, who was as good at ceramics as Bodie was at lithics, belted out a “Hey, Faye!” that could be heard across three counties.

A man Faye didn’t know stood at Dr. Mailer’s elbow. Another stranger crouched near the professor’s foot, poking at something embedded in the soil. Dr. Mailer stepped over him, extending a hand to squeeze Faye’s elbow.

“Welcome, Faye. You, too, Joe.” He reached around her to grasp Joe’s hand warmly. “Oke and Chuck, meet our last two team members.”

The crouching archaeologist rose to his full height, which wasn’t all that much. Barrel-chested and stocky, he was a few inches taller than Faye, but she herself hardly cleared five feet. A smile lit his dark rugged face. “I understand Faye and I have a lot in common. We were both lucky enough to grow up surrounded by our ancestors’ junk. Welcome to my playground.”

So this was Dr. Oka Hofobi Nail, who grew up pulling stone tools and potsherds out of his family’s vegetable garden. His first act as a Ph.D. had been to secure funding to excavate in his own back yard.

A sad truth of archaeology was that sites were not excavated merely because they were interesting, or because they held the potential to explain something important about humanity’s past. Archaeology is labor-intensive. Earth doesn’t turn itself over. Artifacts don’t leap out of the ground unassisted, then clean and catalog themselves. Those artifacts don’t explain themselves, and they don’t document that explanation in a publishable report, either.

Dr. Nail had found a fascinating site, no question, but he would still be working it himself if the state of Mississippi hadn’t wanted to do some road construction. In the course of straightening a bad curve, those road crews would wipe out this occupation site. Faye and her colleagues had been contracted to document it before it was destroyed, which she found depressing when she allowed herself to think about it too much. So she tried not to.

When she set those mixed feelings aside, Faye actually had very high hopes for this project. Oka Hofobi had been politically and financially savvy enough to team with Dr. Mailer, whose reputation was sufficient to secure the client’s trust and whose horde of graduate students was sufficient to get the work done cheaply.

Even better, the makeup of this project team represented a real chance to begin healing the long-standing rift between Native Americans and the archaeological profession. Oka Hofobi, a Choctaw, would have the insight to keep them from stubbing their toe when dealing with the Mississippi Band of the Choctaw Indians, who were a powerful force in this neck of the woods.

Joe, who was mostly Creek, should add to their credibility in the Choctaws’ eyes. Toneisha, an African-American from Memphis, and Faye, whose ancestry was best described as “all-of-the-above,” would do their part to dispel the white-bread atmosphere that typically clings to archaeological crews. Given what she knew about the relaxed personalities of her co-workers, there was even some danger that this job might be fun.

Faye had chosen to spend several years of her life virtually alone on the island passed down to her by her family. Naturally introspective, she had thrived on the work of restoring her ancestral home, so much so that she hadn’t minded her isolation much, but she’d been lonely until Joe came to live with her. Going back to school to earn the education she craved had thrown her into contact with a whole world of youthful, vital, energetic people. She loved her work, and she enjoyed her colleagues, even though she was invariably the quietest member of any team.

“I don’t think either of you have met Chuck Horowitz.” Dr. Mailer gestured to the blond man beside him, whose craggy features matched his angular body. “I expect he’ll be working very closely with you, Joe, since I hear you’re the best flintknapper around. Chuck’s a crackerjack lithics analyst. He can take a pile of flint flakes and reassemble them into the rock somebody used two thousand years ago to make a projectile point. Well, minus the projectile point. But if we dig that point up, Chuck could match it to the flakes of the original rock and rebuild it, no problem.”

Chuck looked at Joe without speaking, then turned his attention to Faye. His gaze started somewhere near her nose, then wandered downward while Dr. Mailer continued speaking. “Faye’s lithics skills aren’t too shabby, either. She was the top student in my class last semester.”

Chuck’s eyes had reached her chest, where they lingered a few thoughtful seconds before heading south again. In her peripheral vision, Faye caught a flicker of motion as Joe’s relaxed hand became a fist. He was leaning forward, prepared to get in Chuck’s face, but she put out a hand to stop him.

Dr. Mailer wasn’t blind. He demonstrated his superior management skills by smoothly putting himself between Joe and Chuck, who was never remotely aware of his peril. “Chuck, I left my cell phone in the truck. Would you go get it for me?”

“Sure.” Chuck shifted his eyes toward the driveway where the truck sat, displaying almost as much interest in the blue pickup as he had in Faye’s shapelier parts. His stride was so long that he was out of earshot within thirty seconds.

“It takes an, er, ‘special’ kind of brain to do the kind of detail work Chuck does every day,” Dr. Mailer offered awkwardly. “Social graces aren’t a big part of his skill set.”

Joe was not mollified. Faye noticed that Toneisha and Bodie sported clenched fists and jaws themselves. Having dealt with problem employees, she felt for Dr. Mailer.

“It’s okay,” she said. “He’s clearly not stupid. Just explain to him that he’s got to keep his eyes to himself.” Toneisha’s firm nod said that Faye wasn’t Chuck’s first victim.

“I wish I could see these things coming,” the professor said. “Then I could just sit Chuck down and spell things out for him all at once. But he just keeps finding new ways to be inappropriate. Maybe it would help if I bought him an etiquette book.” There was a moment of silence while the group pondered the ineffectiveness of that approach. “Well, no time like the present.” He crossed the distance between him and Chuck at a slow trot.

Eager to distract her colleagues from a problem that centered on her breasts, Faye dropped to a squat to get a better look at the soil that Oka Hofobi had been examining when she walked up. “What did you find here?”

“Just a potsherd,” he said, bending down to show her a thumbnail-sized object that would have looked like a chunk of raw clay to most people. Faye’s friends gathered around it like kids goggling over a new video game. “I’ve been finding stuff here since I was five years old. Want to see?” Four open grins said that his colleagues most assuredly did.