Eight Little Piggies (21 page)

Read Eight Little Piggies Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

And yet I still

see

Devil’s Tower in my mind when I think of that growing dot on the horizon. I see it as clearly and as surely as ever, though I now know that the memory is false.

This has been a long story for a simple moral. Papa Joe, the wise old peasant in a natty and elegant business suit, told me on those steps to be wary of all blandishments and to trust nothing that cannot be proved. We must extend his good council to our own interior certainties, particularly those that we never question because we regard eyewitnessing as paramount in veracity.

Yours truly on the fateful steps.

Photograph by Eleanor Gould

.

Of course we must treat the human mind with respect, for nature has fashioned no more admirable instrument. But we must also struggle to stand back and to scrutinize our own mental certainties. This last line poses an obvious paradox, if not an outright contradiction, and I have no resolution to offer. Yes, step back and scrutinize your own mind. But with what?

KOKO

, the obsequious tailor promoted to public executioner in Gilbert and Sullivan’s

Mikado

, maintains “a little list of society offenders who might well be underground”—and he means dead and buried, not romantically in hiding. He places into the lengthy ledger of those “who never would be missed,” a variety of miscreants, including nearly all lawyers and politicians, and even, in a bow to his Victorian prejudices (the true setting beneath the Japanese exterior), “that singular anomaly, the lady novelist.” But the most deserving character in Koko’s compendium, for he haunts all times and places, is “the idiot who praises, with enthusiastic tone, all centuries but this, and every country but his own.”

Admittedly, we do live in a conceptual trough that encourages such yearning for unknown and romanticized greener pastures of other times. The future doesn’t seem promising, if only because we can extrapolate some disquieting present trends into further deterioration: pollution, nationalism, environmental destruction, and aluminum bats. Therefore, we tend to take refuge in a rose-colored past—lemonade and cookies in a rocking chair on the porch of a warm summer’s evening. (I actually participated in all these lovely anachronisms, after a lecture last year, in the intellectually dynamic but architecturally frozen Victorian village of Chautauqua, and I was thoroughly charmed until I remembered that, at the actual time recaptured à la Rockwell, my ancestors worked in sweatshops and lived in tenements, while all black people in town probably dwelled in shacks, literally on the other side of the railroad tracks.)

Foolish romanticism about the past feeds on our selective memory, our fundamental human ability—the only rescue from madness in this world of substantial woe—to discard the ugly and reconstruct our former lives and surroundings to our liking. I do not doubt the salutary, even the essential, properties of this curiously adaptive human trait, but we must also record the down side. Legends of past golden ages become impediments when we try to negotiate our current dilemmas. Blubbery nostalgia clouds any hope for rational understanding. (I don’t remember the fifties as a wonderfully pleasant and carefree time, and nostalgia for that particular decade of McCarthyism and the cold war seems strongest in young people who weren’t even alive then!) Mythology about a happy and simpler past also presents a seemingly limitless arena for commercial exploitation.

I encountered an interesting, though minimally disturbing, example of this commercial side during a recent family visit last month to the Amana Colonies in Iowa. The seven Amana villages were founded in the mid-nineteenth century by German pietists, members of the Society of True Inspirationists who, like so many religious minorities, left a scene of Old World persecution for a new life in America. They first settled near Buffalo, New York, and then, in 1855, moved to Iowa, spurred westward by cheap, abundant, and fertile land.

Utopian communities in America had variable success; few lasted for very long, and those that survived usually held their membership tight (and unrebellious) by strong, shared religious bonds. Amana was a truly communistic society; members ate in communal kitchens and used no money (common foodstuffs could be taken from supply bins “according to need,” while the colonies issued scrip for purchase of rarer items in company stores). They endured in this admirable and decidedly un-American fashion until 1932, when a variety of inevitabilities, from economic woes of the depression to a “youth revolt” spurred by desire for personal ownership of standard consumer goods, provoked what residents still call the “Great Change.” Amana split its major affairs of church and economy (the former has been declining ever since, the latter booming)—and the work of the fields, shops and industries transmogrified, in the good old American way, into a joint stock company.

The villages remain small and pleasant, displaying an architecture both simple and elegant in Shakeresque fashion. But the main street of Amana (the central village) is abuzz with businesses, all designed to separate tourists from dollars by promoting the bucolic and agrarian simplicity of a romanticized past. Some, like the Amana Furniture Shop, at least feature indigenous (if remarkably pricy) crafts of the original inhabitants; others offer utilitarian, and more economically accessible, products of local bakeries and vineyards. But many ply the objects of other states and nations, forging their link to Amana only in the “product image” of nostalgia and bucolia—and producing a dispiriting sameness that struck me as a country counterpart to the identical Crabtree and Evelyn soap store found in every yuppie boutique mall of urban America.

The best evidence of conscious intent in this well-crafted commercial image lies in the near invisibility imposed upon the largest building and biggest employer in the region—Amana Refrigeration, Inc., covering 1.2 million square feet in the territorial heart of Middle Amana. The company is not mentioned in the official brochure, and its location goes unannounced on the official map. No leaflet or flyer can be found at the official visitors center, although every tiny shop and country product receives copious notice and advertisement. Yet, surely, most Americans know the name Amana through the fine refrigerators, air conditioners, and microwave ovens manufactured by this exemplary company.

We might attribute this strange silence to justice or oversight if Amana Refrigeration bore no relationship to the villages, or if the factory sought some form of local anonymity, but neither argument holds. The company was founded in 1934, by George C. Foerstner, an Amana resident freed to indulge his commercial skills by the Great Change. Foerstner’s dubious and personal use of the Amana name created tension with the Amana Society, the joint stock company formed to manage village businesses after the Great Change. This tension ended creatively in 1936, when the Amana Society bought the plant and made Foerstner its principal manager. The society ran the factory with outstanding success until 1965, when Raytheon purchased the name and works to the great benefit of the villages (a deeper source of current prosperity, I would guess, than apricot bread or rhubarb wine).

Moreover, the factory does not hide itself behind a facade of corn stalks. Hourly tours are offered to the public from a spacious and well-appointed visitors’ center (though no notice of the tours can be found in any standard tourist literature available everywhere else within miles). You will not, I trust, charge me with unwarranted cynicism if I conclude that the villages are trying their damnedest to sequester the most prominent bearer of their name in the interest of a bucolic vision that has become eminently profitable itself.

In any case, I confess that the new image of the old is entirely infectious. I was having a wonderful time reading old German hymnals and samplers in the museum, watching the inevitable blacksmith at work, even copping a free sip of that rhubarb wine. I almost began to picture myself in this better and innocent world, supping freely with my fellows and bringing in the sheaves: no more essay deadlines, and no more suffering with the Boston Red Sox; no nukes, no seatbelts, no sweat but by the honest brow.

Then I came upon the Great Reminder (make that capital G, capital R) so freely available in any town as the ultimate antidote to waves of romantic nostalgia for a simpler past—the gravestones of dead children. In 1834, as the True Inspirationists began to contemplate their move to America, Friedrich Rückert wrote the set of poems that Gustav Mahler would later use for his searing song cycle of 1905—

Kindertotenlieder

, or “songs for dead children.” Rich or poor, city or country, all nineteenth-century parents knew that many of their children would never enter the adult world. All my Victorian heroes, Darwin and Huxley in particular, lost beloved children in heartrending circumstances. I cannot believe that the raw pain could ever be much relieved by a previous, abstract knowledge of statistical inevitability—and, on this powerful basis alone, I would never trade even the New York subways for a life behind John Deere’s plow that broke the plains. Imagine the mourning, or just the constant anxiety:

In diesem Wetter, in diesem Braus

nie hätt’ ich gesendet die Kinder hinaus!

(In this weather, in this rainstorm, I would never have let the children outside.)

The graveyard of Middle Amana is spartan in its simplicity. The identical, small white stones are laid out in rows, by strict sequence of death date, starting in the upper left corner and proceeding in book order. The German names are a panoply of objects, professions, descriptions, and moral states—Salome Kunstler (artist), Frau Geiger (violin), and Herr Rind (cow). The longer names do not fit across the small stone, and inscriptions must depart from ultimate simplicity by arching the many letters between the severe borders—Herr Schmiedehammer (sledgehammer), Morgenstern (morning star), and Schuhmacher (shoemaker).

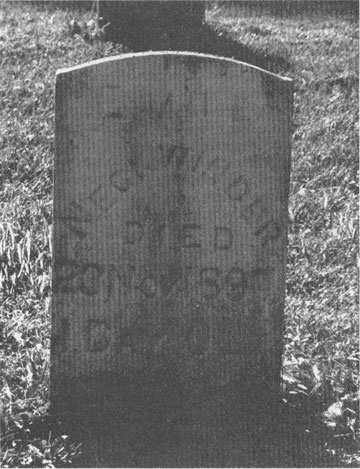

I was looking for more of the arching names when I came upon a particularly stark example of the Great Reminder. The stone read, simply: “Emil Neckwinder, died 23 Nov. 1897, 1 day olt” (a conflation of the German “alt” and the English “old”—an example of languages and cultures in transition). Emil’s twin sister Emma lies just beside him—“died 11 Dez. [again the German spelling], 3 weeks olt.”

The loss of twins, though tragic, would not mark an unusual event. But the neighboring disruption of symmetry caught my attention, for two stones broke the severe geometrical pattern of even arrays. They stand in the space between two rows, directly in front of Emil and Emma’s last resting place. In 1904, Frau Neckwinder bore another set of twins, and named them once more with

E

. Again, they both died—Evaline on May 23 “0 week alt” (fully in German this time), Eva on September 27, “4 months olt.” The geometry itself is so eloquent; what more need be said?—the exception in an otherwise unvarying order of even rows, the intercalation into a linear sequence, permitted so that both pairs of infant twins might lie together in death.

Nearer my home in Lexington, in the graveyard just behind the Commons where our nation began in blood on April 19, 1775, a larger stone marks another kind of dying during our Revolutionary War: “This monument is erected to the memory of 6 children of Mr. Abijah Childs and Mrs. Sarah his wife.” All died between August 19 and September 6 of 1778, presumably in an epidemic of infectious disease now quickly and eminently curable: Sarah at age thirteen (on August 28), Eunice at age twelve (on August 23), Abijah, Jr., at age eleven (on September 6), Abigail at age seven (on August 29), Benjamin at age four (on August 24), and Moses at “3 wanting 8 days” (on August 19.)

The gravestone of the infant Emil Neckwinder who died in his first day of life.

Photograph by Deborah Gould

.

Abijah, Sr., and Sarah lie behind, the husband dead at age seventy on August 30, 1808, his wife at age seventy-eight on March 3, 1812, as another war began. Sarah had to endure the death of at least one more child—Isaac, who must have been but a year old when a plague swept six siblings away, and who died on November 20, 1811, at age thirty-four. Isaac’s grave bears one of the four-line doggerels so common on headstones of the time:

Death like an overflowing flood

Doth sweep us all away.

The young, the old, the middle aged

All to death become a prey.

My hands are on the gravestones of one pair of Neckwinder twins. Note the markers of the second set of twins in the foreground.

Photograph by Deborah Gould

.

These inscriptions are particularly poignant on the gravestones of children and young adults. Most state a rote acceptance of the Lord’s inscrutable will and read like a mantra copied from a pattern book (the source, I suspect, for most inscriptions, given their incessant repetition). Good psychology for mourners perhaps, but forgive a modernism if I doubt the sincerity of stated calm and understanding. Sometimes, a lament of sadness strikes closer to immediate reactions—as in this verse for three-month-old Nathan, on a stone for another family, but standing right next to the grave of Abijah Childs, Sr.