Eight Little Piggies (36 page)

Read Eight Little Piggies Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

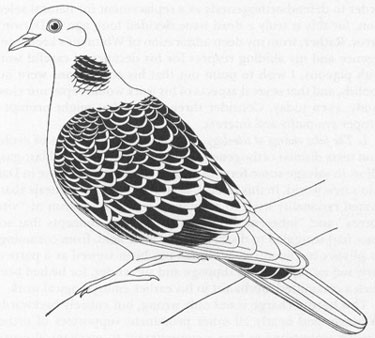

Darwin’s illustration of the showiest of all pigeon breeds—the English fantail. This figure comes from his 1868 book:

The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication. Courtesy of Department of Library Services, American Museum of Natural History

.

Darwin, of course, was well aware of the logic of this destructive argument. He countered by claiming that, in fact, variation has no inherent direction and occurs “at random” relative to the favored path of natural selection. (This debate set the context for Darwin’s confusing claim that variation is random, a statement that has led many people into the worst vernacular misconception about Darwinism: the false belief that Darwin viewed evolutionary change itself as random, and that the manifest order of life therefore disproves his theory. In Darwin’s scheme, variation is random, but natural selection is a deterministic force, adapting organisms to changes in their local environments. In fact, Darwin upheld the randomness of variation in order to empower natural selection as a directional agent.) If variation is only random raw material, occurring in no favored direction relative to environmental advantages, then some other force must shape this formless potential into adaptive change. Random raw material requires another mechanism to supply direction by carving out and preserving the advantageous portion—and natural selection plays this role in Darwin’s system. But orthogenetically directed variation requires no other shaping force and can set an evolutionary trend all by itself.

Whitman therefore set out to prove that an inherent trend in variation pervades the pigeon lineage—a trend too powerful for natural selection to alter in direction or even to slow substantially. Whitman based his argument on patterns of coloration and began by reversing Darwin’s assumption about the plumage of parental forms.

The feral pigeons that speckle our public statuary show two basic color patterns in their extensive repertoire of variation. Some have two black bars on the front edges of their wings and a uniform gray color elsewhere; others develop black splotches, called checkers, on some or all wing feathers, but also retain the two bars (though usually in more indistinct form). The bars, in any case, are composed of checkers (on several adjacent feathers) that line up to produce the impression of a broad continuous stripe (see figures taken from Whitman’s posthumous monograph).

Darwin had assumed that ancestral pigeons were two-barred and that checkers represent an evolved modification by intensification of coloration. Whitman cleanly reversed Darwin’s perspective:

The latter [two-barred] was regarded by Darwin as the typical wing pattern for

Columba livia

; the former [checkered] was supposed to be a variation arising therefrom, a frequent occurrence but of no importance. Just the contrary is true; the checkered pigeon represents the more ancient type, from which the two-barred type has been derived.

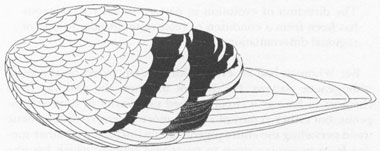

Whitman’s figure of the two-barred wing pattern, which he regarded as an advanced state in his orthogenetic sequence.

Courtesy of Department of Library Services, American Museum of Natural History

.

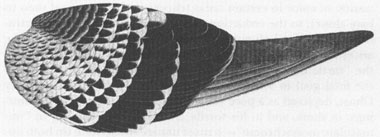

Whitman’s illustration of the checkered pattern—the primitive state in the evolution of pigeon wing colors.

Courtesy of Department of Library Services, American Museum of Natural History

.

This reversal is of no great significance in itself, unless you happen to be a pigeon fancier devoted to the peculiarities of these generally unloved creatures. But Whitman properly made much of his inversion because his favored sequence of checkers-to-bars formed the major part of his proposed (and inexorable) orthogenetic sequence of internally prescribed variation—an evolutionary pattern inherent in the biological organization of pigeons and quite beyond the power of natural selection to deflect. The orthogenetic trend, Whitman argued, moved from original diffusion to later concentration of color. Checkers plus indistinct bars must precede clear bars and no checkers. In the lines following the quotation just cited, Whitman writes:

The direction of evolution in pattern in the rock pigeons has been from a condition of relative uniformity to one of regional differentiation.

But Whitman had an even bolder vision, based on the same orthogenetic pattern. He did not interpret the pathway from checkers to bars as a circumscribed peculiarity of domestic pigeons, but rather as part of a much more extensive orthogenetic trend pervading the entire pigeon family (including all other species from mourning dove to passenger pigeon, which became extinct in the decade between Whitman’s death and the posthumous publication of his monograph), and perhaps even all coloration in birds—an inherent and ineluctable progression from an original homogeneous checkering on all feathers; to the concentration of color in certain areas (checkers plus bars, and then to bars alone); to the reduction and weakening of these concentrations; to the final elimination of all color. Whitman located the ancestral state in the uniform checkering of some species—the “turtle dove pattern” in his terminology (see figure)—and the final goal in some idealized, albinized version of the Holy Ghost, depicted as a pure white dove in so many medieval paintings: in short, and in his words, from uniform spotting to “immaculate monochrome”—a most unpigeonlike state (in both appearance and deed), at least in our metaphors. In a remarkable vision of inexorable movement through the entire great family of pigeons, Whitman writes:

When we look around among allied species and see the same bars reduced to about half dimensions in the rock pigeon of Manchuria, reduced to mere remnants of two to six spots in the stock dove, carried to complete obsoletion [

sic

] or to a few shadowy reminiscences in…

Columba rufina

of Brasil, gone past return in some of our domestic breeds and in many of the wild [doves and pigeons]—when we see all these stages multiplied and varied through some 400 to 500 wild species and 100 to 200 domestic breeds, and in general tending to the same goal, we begin to realize that they are…slowly passing phases in the progress of an orthogenetic process of evolution, which seems to have no fixed goal this side of an immaculate monochrome—possibly none short of complete albinism.

The fully checkered turtledove pattern, which Whitman regarded as the original state in his orthogenetic sequence.

Courtesy of Department of Library Services, American Museum of Natural History

.

Moreover, while the progress of the trend may be “lengthened or shortened, strengthened or weakened” by such subsidiary forces as natural selection, the orthogenetic sequence is invariable: “The steps are seriated in a causal, genetic order—an order that admits no transpositions, no reversals, no mutational skips, no unpredictable chance intrusions.” When we discern the proper sequence of orthogenetic stages, evolution may become a predictive science: “Not only is the direction of the change hitherto discoverable, but its future course is predictable.”

I have not resurrected Whitman’s largely forgotten work in order to defend orthogenesis as a replacement for natural selection, for this is truly a dead issue decided long ago in Darwin’s favor. Rather, from my deep admiration of Whitman’s keen intelligence and my abiding respect for his decades of careful work with pigeons, I wish to point out that his conclusions were not foolish, and that several aspects of his work would repay our close study, even today. Consider three points that might prompt a proper sympathy and interest.

1.

The false charge of teleology

. The standard one-liners of evolution texts dismiss orthogenesis as a theistically inspired last-gasp effort to salvage some form of inherent goal and purpose in Darwin’s new world. In this canard, supporters of orthogenesis abandoned rationality itself to embrace a woolly mysticism of “vital forces” and “inherent directions”—the very concepts that science had struggled to discard in field after field, from cosmology to physics to chemistry. Whitman has been viewed as a particularly sad example of this slippage and surrender, for he had been such a committed mechanist in his earlier embryological work.

This hurtful charge is not only wrong, but entirely backwards. Whitman and nearly all other prominent supporters of orthogenesis maintained as firm a commitment to mechanical causation, and as strong an aversion to mystical or spiritual direction, as any contemporary in this late-nineteenth-century age of industrial order. In the opening paragraph of his 1919 monograph on pigeons, Whitman wrote:

His [Darwin’s] triumph has won for us a common height from which we see the whole world of living beings as well as all inorganic nature; phenomena of every order we now regard as expressions of natural causes. The supernatural has no longer a standing in science; it has vanished like a dream, and the halls consecrated to its thraldom of the intellect are becoming radiant with a more cheerful faith.

In fact, Whitman’s orthogenesis arose from his mechanical perspective, not in opposition to his former life’s work. The orthogenetic trend did not follow a mystical impulse from outside, but a mechanistic drive from within, based upon admittedly unknown laws of genetics and embryology. His work on cell lineages had mapped the fate of earliest cells in the embryo, and had indicated that the source of eventual organs could be specified even in the tiny and formless clump of initial cells. If embryos grew so predictably, why should evolutionary change be devoid of similar order. “I venture to assert,” Whitman wrote, “that variation is sometimes orderly and at other times rather disorderly, and that the one is just as free from teleology as the other…. If a designer sets limits to variation in order to reach a definite end, the direction of events is teleological; but if organization and the laws of development exclude some lines of variation and favor others, there is certainly nothing supernatural in this.”

2.

Whitman’s evidence

. Modern detractors who misconstrue orthogenesis as old-fashioned teleology often assume that its supporters could only have been working on hope and the flimsiest of supposed evidence. But Whitman spent decades gathering reams of fascinating data (not all properly interpreted in our view, but still full of interest). He marshaled three major sources of evidence to support his orthogenetic theory: breeding, comparative anatomy, and ontogeny (the growth of individual birds).

In breeding, he found that he could develop a two-barred race from checkered parents by selecting birds with the weakest checkers in each generation. But he could never produce checkered birds from two-barred progenitors. In comparative anatomy, he argued that species judged more ancestral on other criteria grew plumages of early stages in the orthogenetic series. In ontogeny, he found that juvenile plumage exhibited earlier stages than adult feathers (a juvenile bird might moult its checkered feathers and then grow a two-barred adult plumage). Most nineteenth-century biologists believed that “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny”—a mouthful meaning that individuals, in their embryology and growth, tend to pass through stages representing adult forms of their ancestry. Juvenile plumage would therefore represent an ancestral condition. The law of recapitulation is wrong (see my book,

Ontogeny and Phylogeny

), but you can’t blame Whitman for accepting the consensus of his time.