Einstein (68 page)

Authors: Walter Isaacson

The most frequent question Einstein was asked was whether he would someday return to Jerusalem to stay. He was unusually discreet in his replies, saying nothing quotable. But he knew, as he confided to one of his hosts, that if he came back he would be “an ornament” with no chance of peace or privacy. As he noted in his diary, “My heart says yes, but my reason says no.”

80

NOBEL LAUREATE

1921–1927

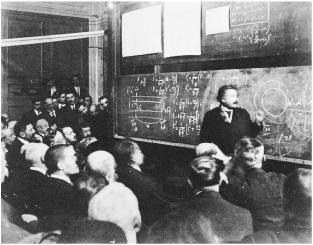

Einstein in Paris, 1922

It seemed obvious that Einstein would someday win the Nobel Prize for Physics. He had, in fact, already agreed to transfer the money to his first wife, Mileva Mari , when that occurred. The questions were: When would it happen? and, For what?

, when that occurred. The questions were: When would it happen? and, For what?

Once it was announced—in November 1922, awarding him the prize for 1921—the questions were: What took so long? and, Why “especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect”?

It has been part of the popular lore that Einstein learned that he had finally won while on his way to Japan. “Nobel Prize for physics awarded to you. More by letter,” read the telegram sent on November 10. In fact, he had been alerted as soon as the Swedish Academy made the decision in September, well before he left on his trip.

The chairman of the physics award committee, Svante Arrhenius, had heard that Einstein was planning to go to Japan in October, which meant that he would be away for the ceremony unless he postponed the trip. So he wrote Einstein directly and explicitly: “It will probably be very desirable for you to come to Stockholm in December.” Expressing a principle of pre–jet travel physics, he added, “And if you are then in Japan that will be impossible.”

1

Coming from the head of a Nobel Prize committee, it was clear what that meant. There are not a lot of other reasons for physicists to be summoned to Stockholm in December.

Despite knowing that he would finally win, Einstein did not see fit to postpone his trip. Partly it was because he had been passed over so often that it had begun to annoy him.

He had first been nominated for the prize in 1910 by the chemistry laureate Wilhelm Ostwald, who had rejected Einstein’s pleas for a job nine years earlier. Ostwald cited special relativity, emphasizing that the theory involved fundamental physics and not, as some Einstein detractors argued, mere philosophy. It was a point that he reiterated over the next few years as he resubmitted the nomination.

The Swedish committee was mindful of the charge in Alfred Nobel’s will that the prize should go to “the most important discovery or invention,” and it felt that relativity theory was not exactly either of those. So it reported that it needed to wait for more experimental evidence “before one can accept the principle and in particular award it a Nobel prize.”

2

Einstein continued to be nominated for his work on relativity during most of the ensuing ten years, gaining support from distinguished theorists such as Wilhelm Wien, although not yet from a still-skeptical Lorentz. His greatest obstacle was that the committee at the time was leery of pure theorists. Three out of the committee’s five members throughout the period from 1910 to 1922 were experimentalists from Sweden’s Uppsala University, known for its fervent devotion to perfecting experimental and measuring techniques. “Swedish physicists with a strong experimentalist bias dominated the committee,” notes Robert Marc Friedman, a historian of science in Oslo. “They held precision measurement as the highest goal for their discipline.”

That is one reason Max Planck had to wait until 1919 (when he was awarded the delayed prize for 1918) and why Henri Poincaré never won at all.

3

The dramatic announcement in November 1919 that the eclipse observations had confirmed parts of Einstein’s theory should have made 1920 his year. By then Lorentz was no longer such a skeptic. He along with Bohr and six other official nominators wrote in support of Einstein, mostly focusing on his completed theory of relativity. (Planck wrote in support as well, but his letter arrived after the deadline for consideration.) As Lorentz’s letter declared, Einstein “has placed himself in the first rank of physicists of all time.” Bohr’s letter was equally clear: “One faces here an advance of decisive significance.”

4

Politics intervened. Up until then, the primary justifications for denying Einstein a Nobel had been scientific: his work was purely theoretical, it lacked experimental grounding, and it putatively did not involve the “discovery” of any new laws. After the eclipse observations, the explanation of the shift in Mercury’s orbit, and other experimental confirmations, these arguments against Einstein were still made, but they were now tinged with more cultural and personal bias. To his critics, the fact that he had suddenly achieved superstar status as the most internationally celebrated scientist since the lightning-tamer Benjamin Franklin was paraded through the streets of Paris was evidence of his self-promotion rather than his worthiness of a Nobel.

This subtext was evident in the internal seven-page report prepared by Arrhenius, the committee chairman, explaining why Einstein should not win the prize in 1920. He noted that the eclipse results had been criticized as ambiguous and that scientists had not yet confirmed the theory’s prediction that light coming from the sun would be shifted toward the red end of the spectrum by the sun’s gravity. He also cited the discredited argument of Ernst Gehrcke, one of the anti-Semitic antirelativists who led the notorious 1920 rally against Einstein that summer in Berlin, that the shift in Mercury’s orbit could be explained by other theories.

Behind the scenes, Einstein’s other leading anti-Semitic critic, Philipp Lenard, was waging a crusade against him. (The following year, Lenard would propose Gehrcke for the prize!) Sven Hedin, a

Swedish explorer who was a prominent member of the Academy, later recalled that Lenard worked hard to persuade him and others that “relativity was really not a discovery” and that it had not been proven.

5

Arrhenius’s report cited Lenard’s “strong critique of the oddities in Einstein’s generalized theory of relativity.” Lenard’s views were couched as a criticism of physics that was not grounded in experiments and concrete discoveries. But there was a strong undercurrent in the report of Lenard’s animosity to the type of “philosophical conjecturing” that he often dismissed as being a feature of “Jewish science.”

6

So the 1920 prize instead went to another Zurich Polytechnic graduate who was Einstein’s scientific opposite: Charles-Edouard Guillaume, the director of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, who had made his modest mark on science by assuring that standard measures were more precise and discovering metal alloys that had practical uses, including making good measuring rods. “When the world of physics had entered upon an intellectual adventure of extraordinary proportions, it was remarkable to find Guillaume’s accomplishment, based on routine study and modest theoretical finesse, recognized as a beacon of achievement,” says Friedman. “Even those who opposed relativity theory found Guillaume a bizarre choice.”

7

By 1921, the public’s Einstein mania was in full force, for better or worse, and there was a groundswell of support for him from both theoreticians and experimentalists, Germans such as Planck and non-Germans such as Eddington. He garnered fourteen official nominations, far more than any other contender. “Einstein stands above his contemporaries even as Newton did,” wrote Eddington, offering the highest praise a member of the Royal Society could muster.

8

This time the prize committee assigned the task of doing a report on relativity to Allvar Gullstrand, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Uppsala, who had won the prize for medicine in 1911. With little expertise in either the math or the physics of relativity, he criticized Einstein’s theory in a sharp but unknowing manner. Clearly determined to undermine Einstein by any means, Gullstrand’s fifty-page report declared, for example, that the bending of light was not a true test of Einstein’s theory, that the results were not experimentally

valid, and that even if they were there were still other ways to explain the phenomenon using classical mechanics. As for Mercury’s orbit, he declared, “It remains unknown until further notice whether the Einstein theory can at all be brought into agreement with the perihelion experiment.” And the effects of special relativity, he said, “lay below the limits of experimental error.” As one who had made his name by devising precision optical measuring instruments, Gullstrand seemed particularly appalled by Einstein’s theory that the length of rigid measuring rods could vary relative to moving observers.

9

Even though some members of the full Academy realized that Gullstrand’s opposition was unsophisticated, it was hard to overcome. He was a respected and popular Swedish professor, and he insisted both publicly and privately that the great honor of a Nobel should not be given to a highly speculative theory that was the subject of an inexplicable mass hysteria that would soon deflate. Instead of choosing someone else, the Academy did something that was less (or more?) of a public slap at Einstein: it voted to choose nobody and tentatively bank the 1921 award for another year.

The great impasse threatened to become embarrassing. His lack of a prize had begun to reflect more negatively on the Nobel than on Einstein. “Imagine for a moment what the general opinion will be fifty years from now if the name Einstein does not appear on the list of Nobel laureates,” wrote the French physicist Marcel Brillouin in his 1922 nominating letter.

10

To the rescue rode a theoretical physicist from the University of Uppsala, Carl Wilhelm Oseen, who joined the committee in 1922. He was a colleague and friend of Gullstrand, which helped him gently overcome some of the ophthalmologist’s ill-conceived but stubborn objections. And he realized that the whole issue of relativity theory was so encrusted with controversy that it would be better to try a different tack. So Oseen pushed hard to give the prize to Einstein for “the discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect.”

Each part of that phrase was carefully calculated. It was not a nomination for relativity, of course. In fact, despite the way it has been phrased by some historians, it was not for Einstein’s theory of light

quanta, even though that was the primary focus of the relevant 1905 paper. Nor was it for any

theory

at all. Instead, it was for the

discovery

of a

law.

A report from the previous year had discussed Einstein’s “

theory

of the photoelectric effect,” but Oseen made clear his different approach with the title of his report: “Einstein’s

Law

of the Photoelectric Effect” (emphasis added). In it, Oseen did not focus on the theoretical aspects of Einstein’s work. He specified instead what he called a fundamental natural law, fully proven by experiment, that Einstein propounded: the mathematical description of how the photoelectric effect was explained by assuming that light was absorbed and emitted in discrete quanta, and the way this related to the frequency of the light.

Oseen also proposed that giving Einstein the prize delayed from 1921 would allow the Academy to use that as a basis for simultaneously giving Niels Bohr the 1922 prize, because his model of the atom built on the laws that explained the photoelectric effect. It was a clever coupled-entry ticket for making sure that the two greatest theoretical physicists of the time became Nobel laureates without offending the Academy’s old-line establishment. Gullstrand went along. Arrhenius, who had met Einstein in Berlin and been charmed, was now also willing to accept the inevitable. On September 6, 1922, the Academy voted accordingly, and Einstein and Bohr were awarded the 1921 and 1922 prizes, respectively.

Thus it was that Einstein became the recipient of the 1921 Nobel Prize, in the words of the official citation, “for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect.” In both the citation and the letter from the Academy’s secretary officially informing Einstein, an unusual caveat was explicitly inserted. Both documents specified that the award was given “without taking into account the value that will be accorded your relativity and gravitation theories after these are confirmed in the future.”

11

Einstein would not, as it turned out, ever win a Nobel for his work on relativity and gravitation, nor for anything other than the photoelectric effect.