Eisenhower

Authors: Jim Newton

Also by Jim Newton

Justice for All:

Earl Warren and the Nation He Made

Copyright © 2011 by Jim Newton

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

DOUBLEDAY

and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Jacket design by John Fontana

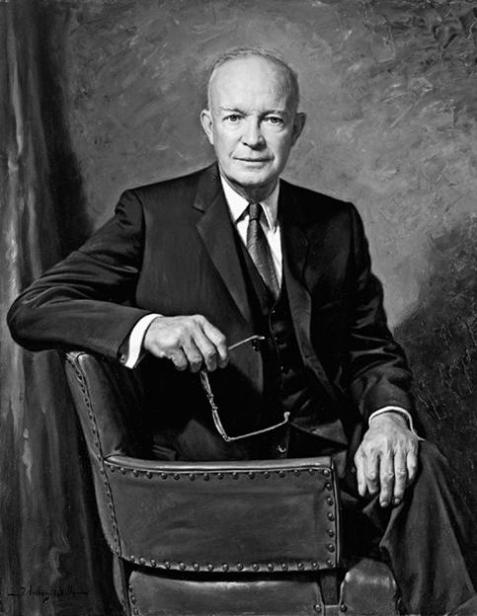

Jacket photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress

Frontispiece courtesy of White House Historical Association (White House Collection)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Newton, Jim, 1963–

Eisenhower : the White House years/ by Jim Newton.—1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Eisenhower, Dwight D. (Dwight David), 1890–1969. 2. United States—Politics and government—1953–1961. 3. Presidents—United States—Biography. I. Title.

E836.N49 2011

973.921092—dc22

[B] 2011010759

eISBN: 978-0-385-53453-6

v3.1

To Jack and Karlene, with love

CONTENTS

1. The Lessons of Family

2. The Mentoring of Soldiers

3. Learning Politics

4. From Candidate to President

5. Changing America’s Course

6. Consequences

7. Security

8. “McCarthywasm”

9. Revolutions

10. Heartache

11. Crisis and Revival

12. On the Edge

13. The Press of Change, the Price of Inaction

14. Nuclear Interlude

15. Many Ways to Fight

16. Loss

17. The Final Months

18. Rejection

19. Farewell

Epilogue

INTRODUCTION

May 1, 1958, was a fairly quiet day in the world. It was international Communism’s traditional date of celebration, and Moscow marked the occasion with a peace-themed rally in Red Square, presided over by Nikita Khrushchev and provocatively attended by Gamal Abdel Nasser of the United Arab Republic, ostensibly a Cold War–neutral but often a flirtatious friend of Russia. In London, Labourites hoisted a red flag, while in Nazareth, Moscow’s celebration of peace frayed a bit: eighty people were injured when fighting broke out after Communists heckled a group of labor demonstrators. At the level of diplomacy, the American secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, was pursuing an agreement with the Soviet Union to remove bombers and military bases from the Arctic; Vice President Richard Nixon was in Argentina for the inauguration of Arturo Frondizi, that nation’s first freely elected president in twelve years.

Dwight David Eisenhower, thirty-fourth president of the United States, spent the day at the White House, all but invisible to the outside world. He woke to a cool, sunny morning in the capital and had breakfast with members of his staff at 7:45 a.m. in the White House mess. He arrived at his desk at 8:36 a.m. Looking over his schedule, the president saw that he had a short workday ahead, with just one meeting of consequence.

Five years into his presidency, Eisenhower was in a slump. His approval ratings, which generally hovered between 60 and 70 percent, had fallen below 50 for the first time as the American economy slogged through a mild recession. Knocked down by a heart attack in 1955 and a hospitalization for ileitis in 1956, he was perceived by many journalists and much of the nation’s elite as ailing, ineffectual, and detached, surrounded by scheming, powerful cabinet members who carried out the nation’s work while Ike served as its benign figurehead, devoted to golf and bridge, manipulated by a coterie of shrewd businessmen. The administration’s response to the recession seemed to its critics lamentably typical. The House of Representatives that day passed a bill to extend jobless benefits, but the legislation represented a compromise—liberals had supported larger benefits for longer, while Eisenhower backed a more modest alternative. Eisenhower, one editorial opined, was confronting the nation’s economic difficulties “by the device of wishful thinking.”

Dissatisfaction with Ike was captured that year by Marquis Childs, an influential Washington journalist whose 1958 book,

Eisenhower: Captive Hero

, portrayed the president as indecisive and lazy, stodgy and limited by his military upbringing. “He is moved by forces,” Childs wrote. “He does not undertake to move them himself.” Ike, in Childs’s view, had fallen woefully short of public expectations for his presidency and had failed to marshal the powers of his office. For that, Childs concluded, “Eisenhower … must be put down as a weak president.”

That was Eisenhower as viewed by press and public—limited, captive, disappointing. But on this May Day of 1958, the President Eisenhower invisible to Childs, unappreciated by his critics, was at work offstage on matters of grave consequence. At 9:00 a.m., the president and thirty-four of his most senior and trusted advisers assembled for the 364th meeting of the National Security Council. The meeting opened, as it usually did, with a briefing on world events—updates on fighting in Indonesia and Yemen highlighted the report—then turned to a review of basic U.S. security policy, a matter that had been under constant consideration since Ike’s election in 1952.

For months, Eisenhower’s top aides had grown increasingly restive about the nation’s reliance on massive retaliation as the centerpiece of its strategy to contain Soviet and Chinese Communism. The threat of annihilation had maintained an uneven peace since the end of World War II, and America’s nuclear might had allowed Eisenhower to leverage advantage in conflicts from Berlin to Korea to Taiwan. But as the Soviets gained nuclear strength, America’s allies—and its military leadership—worried that the threat of retaliation was growing hollow. Would the United States actually risk its own destruction to deter a Soviet advance on Austria, say, or Berlin or Vietnam?

On that Thursday morning, it was Secretary of Defense Neil McElroy who opened the argument, noting that his Turkish counterpart had three times during a recent NATO meeting raised questions about whether the United States was actually prepared to live up to its commitment to its allies—“to resist a Soviet attack on one member of the Alliance as an attack on all.” General Maxwell Taylor, chief of staff of the Army, echoed those concerns, citing recent setbacks in Indonesia and the Middle East and warning that the Soviet Union was on the verge of achieving nuclear parity with the United States. Taylor and McElroy proposed to address what they saw as a dangerous trend by adjusting American security policy: rather than relying on the threat of massive retaliation, the United States, they argued, should develop a tactical nuclear capacity to fight limited wars. They acknowledged such a course would be expensive, especially if new, smaller nuclear weapons were to be developed even as the nation continued to arm itself with large deterrent forces. But Eisenhower’s top military advisers insisted that the price was justified; the survival of the Western alliance and, with it, Western civilization itself depended on it.

Secretary of State Dulles, Ike’s closest adviser, agreed with his military counterparts. So grave was the stress on American alliances, he said, that those nations who had bound their fates to that of the United States—many after long urging by Ike and Dulles themselves—would break away if they did not have better assurances that the United States would help protect them. It was thus “urgent for us to develop the tactical defensive capabilities inherent in small ‘clean’ nuclear weapons.” Although Dulles himself was a principal architect of massive retaliation, that approach to deterring war, he now argued, “was running its course” and would soon be obsolete: “In short, the United States must be in a position to fight defensive wars which do not involve the total defeat of the enemy.”

Eisenhower sat quietly as his top aides urgently pressed him to abandon the most fundamental security precept of his presidency, a policy deliberately arrived at beginning with a landmark, classified study in 1953 and patiently pursued in the years since. When Dulles finished, the president noted that he had a “couple of questions.” In fact, they were more in the form of observations. Eisenhower challenged first the utility and then the plausibility of shifting from massive retaliation to flexible response. The nuclear option that his advisers recommended, Eisenhower pointed out, would transform weapons of deterrence into weapons of war, from an umbrella shielding allies to a “lightning rod” drawing fire to earth. Imagine a Soviet attack on Austria, the president said. American repulsion of that assault would never take the form of a “nice, sweet, World War II–type of war.” It would be a fight to the finish. Tactical nuclear weapons would not change that; they would merely escalate conventional war to nuclear war and thus extinction. Massive retaliation, by contrast, was predicated on the premise that an all-out nuclear response was America’s only retort to such an invasion; recognizing that, the Soviets would presumably refrain from courting their own destruction.