El Borak and Other Desert Adventures (28 page)

Read El Borak and Other Desert Adventures Online

Authors: Robert E. Howard

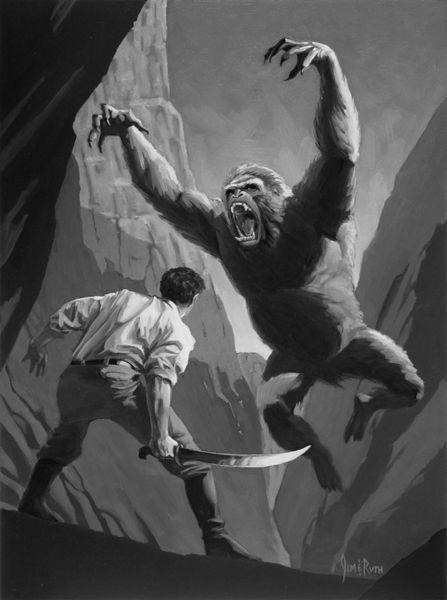

The talon-like nails only shredded his shirt as he sprang clear, slashing as he sprang, and a hideous scream ripped the echoes shuddering through the ridges; the ape’s arm fell to the ground, shorn away at the elbow. With blood spouting from the severed stump the brute whirled and rushed again, and this time its desperate lunge was too lightning-quick for any human thews wholly to avoid.

Gordon evaded the disembowelling sweep of the great misshapen hand with its thick black nails, but the massive shoulder struck him and knocked him staggering. He was carried to the wall with the lunging brute, but even as he was swept backward he drove his knife to the hilt in the great belly and ripped up in the desperation of what he believed was his dying stroke.

They crashed together into the wall, and the ape’s great arm hooked terribly about Gordon’s straining frame; the roar of the beast deafened him as the foaming jaws gaped above his head — then they snapped spasmodically in empty air as a great shudder shook the mighty body. A frightful convulsion hurled the American clear, and he bounded up to see the ape thrashing in its death throes at the foot of the wall. His desperate upward rip had disembowelled it and the tearing blade had ploughed up through muscle and bone to find the fierce heart of the anthropoid.

Gordon’s corded thews were quivering as if from a long-sustained strain. His iron-hard frame had resisted the terrible strength of the ape long enough to permit him to come alive out of that awful grapple that would have torn a weaker man to pieces; but the terrific exertion had shaken even him. Shirt and undershirt had been ripped from him and those horny-taloned fingers had left bloody marks deep-grooved across his back. He was smeared and stained with blood, his own and the ape’s.

“El Borak!

El Borak!”

It was Lal Singh’s voice lifted in frenzy, and the Sikh burst out of the left-hand ravine, a rock in each hand, and his bearded face livid.

His eyes blazed at the sight of the ghastly thing at the foot of the wall; then he had seized Gordon in a desperate grasp.

“Sahib!

Are you slain? You are covered with blood! Where are your wounds?”

“In the ape’s belly,” grunted Gordon, twisting free. Emotional display embarrassed him. “It’s his blood, not mine.”

Lal Singh sighed with gusty relief, and turned to stare wide-eyed at the dead monster.

“What a blow! You ripped him wide open so his guts fell out! Not ten men now alive in the world could strike such a blow. It is the

djinn

of which the girl warned us! And an ape! The beast the Mongols call the Desert Man.”

“Yes. I never believed the tales about them before. Scientific expeditions have tried to find them, but the natives in that part of the Gobi always ran the white men out.”

“Perhaps there are others,” suggested Lal Singh, peering sharply about in the gathering dusk. “It will soon be dark. It will not be well to meet such a fiend in these dark ravines after nightfall.”

“I don’t think. His roars could have been heard all through these gulches. If there had been another, it would have come to his aid, or sounded an answering roar, at least.”

“I heard the bellowing,” said Lal Singh fervently. “The sound turned my blood to ice, for I believed it was in truth a

djinn

such as the superstitious Moslems speak of. I did not expect to find you alive.”

Gordon spat, aware of thirst.

“Well, let’s get moving. We’ve rid the ravines of their haunter, but we can still die of hunger and thirst if we don’t get out. Come on.”

Dusk masked the gullies and hung over the ridges, as they moved off down the right-hand ravine. Forty yards further on the left-hand branch ran back into its brother, as Gordon had believed to be the case. As they advanced, the walls were more thickly pitted with cave-like lairs, in which the rank scent of the ape hung strong. Gordon scowled and Lal Singh swore at the numbers of skeletons which littered the gulch, which evidently had been the monster’s favorite stamping ground. Most of them were of women, and as Gordon viewed those pitiful remnants, a relentless and merciless rage grew redly in his brain. All that was violent in his nature, ordinarily held under iron control, was roused to ferocious wakefulness by the realization of the horror and agony those helpless women had suffered, and in his own soul he sealed the doom of Shalizahr and the human fiends who ruled it. It was not his nature to swear oaths or vow loud vows. He did not speak his mind even to Lal Singh; but his intention to wipe out that nest of vultures in the interests of the world at large took on the tinge of a personal blood-feud, and his determination fixed like iron never to leave the plateau until he had looked upon the dead bodies of Ivan Konaszevski and the Shaykh Al Jebal.

The loom of the mountain was now above them, in tiers of giant cliffs, rising

precipitously above the rim of the bowl which enclosed the sunken labyrinth. The ravine they were following ran into a cleft in the wall of this bowl, beneath the mountain. It became a tunnel-like cavern, receding under the mountain like a well of blackness. There was despair in the Sikh’s voice as he spoke.

“Sahib

, it is a prison from which there is no escape. We can not climb the rim that hems in this depression of gulches. And this cave —”

“Wait!” Gordon’s iron fingers bit into the Sikh’s arm in sudden excitement. They were standing in utter darkness, some yards inside the cave-mouth. He had glimpsed something far down that black tunnel — something that shone like a firefly. But it was steady, not intermittent. It cut through the blackness like a stationary spark of light.

“Come on!” Releasing the Sikh’s arm Gordon hurried down the cavern, chancing a plunge into a pit or a meeting in the dark with some grim denizen of the underworld. He knew what he saw was a star, shining through some cleft in the mountain wall.

As they advanced a faint light illuminated the darkness ahead of them, and presently they saw the cave ended at a blank wall; but in that wall, some ten feet from the floor, there was hole and through it they saw the star and a bit of velvet night-sky. Without a word the Sikh bent his back, gripping his legs above the knees to brace himself, and Gordon climbed onto his shoulders and stood upright, his fingers grasping the rim of the roughly circular cleft. It was four or five feet long, and just big enough for a man to squeeze through. The ape might conceivably have reached it, but he could not have forced his great shoulders through it. Gordon did not believe the masters of Shalizahr knew of that opening.

He wriggled to the other end of the tunnel-like cleft, and peered over the rim. He was looking down on the western flank of the mountain. The hole was a crevice in a cliff which sloped down for three hundred feet, broken by rocks and ledges. He could not see the plateau; a marching row of broken pinnacles rose gauntly between it and his point of vantage. Crawling back, he dropped down inside the cave beside the eager Sikh.

“Is it a way of escape,

sahib

?”

“For you. Lal Singh, you’ve got to go and meet Yar Ali Khan and the Ghilzai. I’m gambling on the chance that he reached Khor and will be back at the outer gates of Shalizahr by sunrise tomorrow. According to my estimate there are at least five hundred fighting men in Shalizahr. Baber Khan’s three hundred can’t take the city in a direct attack. They might surprize the guard at the cleft as I did, might even force their way up the Stair. But to cross the plateau on foot, in the teeth of five hundred rifles under Ivan’s command, would be suicide.

“You’ve got to meet them before they get to the plateau. I think you can

do it. When you’ve squirmed through this hole and climbed down the slope outside, you’ll be outside the ring of crags which surrounds Shalizahr. The only way through those crags is by the cleft through which we came to the plateau. The Ghilzai will come through that cleft. You’ll have to stop them in the canyon the Assassins call the Gorge of the Kings, if at all. To get there you’ll have to skirt the ring of crags, and follow around their western slopes until you hit the canyon. It’ll be rough going, and you may have trouble getting down the cliffs that wall the canyon when you get there. But you’ll have all night to make the trip in.”

“And you,

sahib?”

“I’m coming to that. If you get to the Gorge of the Kings before the Ghilzai come, hide and wait for them. If they’ve already passed through the cleft — you can read their sign — follow them as fast as you can. In any event, see that Baber Khan follows this plan of action: let him take fifty men and make a demonstration against the Stair. If they can climb the ramps and take cover in the boulders at the head of the Stair, so much the better. If not, let them climb the surrounding crags and start shooting at everything in sight on the plateau. The idea is to create a diversion to attract the attention of the men in the city, and if possible to draw them all to the Stair. If they advance down into the canyon, let Baber Khan and his fifty retreat among the crags.

“Meanwhile, do you and Yar Ali Khan lead the rest of the Ghilzai back the way you’ll traverse in reaching the Gorge of Kings. Bring them up that slope and through this cleft and down that ravine where the door in the rock opens into the dungeons under the palace.”

“But what of you?”

“My part will be to open that door for you — from the inside.”

“But this is madness! You can not get back into the city; and if you did, they would flay you alive. But you can not open that door.”

“Another will open it for me. That ape didn’t eat the wretches thrown to him. He wasn’t carnivorous. No ape is. He had to be fed vegetables, or nuts, or roots or something. You saw a man open that door and throw something out. Undoubtedly, it was a bundle of food. They fed it through that door, and they must have fed it regularly. It wasn’t gaunt, by any means.

“I’m gambling that door will be opened tonight. When it opens, I’m going through it. I’ve got to. They’ve got Azizun somewhere in that hellish palace, and only Allah knows what they’re doing to her. Now you go in a hurry. When you get back into the bowl with the Ghilzai, hide them among the gulches and come down the ravine to the door with three or four men. Tap a few times on it with your rifle-butt. That door will be opened whether I’m alive or dead — if I have to come back from Hell and open it. Once in the palace, we’ll make a shambles of Othman and his dogs.”

The Sikh lifted his hand in protest and opened his mouth — then shrugged his shoulders fatalistically and silently acquiesced.

Gordon squatted and the Sikh climbed on his shoulders and stood upright, steadying himself with outstretched hands against the wall. Gordon gripped his ankles with both hands and rose to an upright posture without the aid of his arms, using only his leg muscles to lift himself and the tall man on his shoulders — a feat impossible to most men besides trained acrobats.

In the cleft Lal Singh turned and looked down at his friend.

“What if none comes with food for the beast, and the door is not opened tonight?”

“Then I’ll cut off the ape’s head and throw it over the wall. They’ll open the door then, to see why I’m still alive. Maybe they’ll take me into the palace to torture me when they learn I’ve killed their goblin. Once let me get in there, even if in chains, and I’ll find a way to trick them.

“Here!” Gordon tossed up the long knife. “You may need this.”

“But if you wish to cut off the ape’s head —”

“I’ll saw it off with a sliver of sharp rock — or gnaw it off with my teeth! Get going, confound it!”

“The gods protect you,” muttered the Sikh, and vanished. Gordon heard a clawing and scrambling that marked his course through the cleft, and then pebbles began rattling down the sloping cliff outside.

D

EATH

S

TALKS THE

P

ALACE

Gordon groped his way back through the cavern, and when he came into the comparative light of the gulches, he ran, fleetly and sure-footedly, until he came into the outer ravine and saw the wall and the cliff and the shelf of rock at the other end. The lights of Shalizahr glowed in the sky above the wall, and he could catch the weird melody of whining native citherns. A woman’s voice was lifted in a plaintive song. He smiled grimly at the dark, skeleton-littered gorges about him. So might the lords of Nineveh and Babylon and Susa have revelled, heedless of the captives screaming and writhing and dying in the pits beneath their palaces — ignorant of the red destruction predestined at the maddened hands of those captives.

There was no food on the rocky shelf before the door. He had no way of knowing how often the brute had been fed, and whether it would be fed that night. That it had not been fed he could see, and he believed that food would be put out for it soon. Many hours had elapsed since the Sikh had seen that door opened.

He must gamble with chance, as he so often had. The thought of what

might even then be happening to the girl Azizun made him sweat with fear for her, and maddened him with impatience. But he flattened himself against the rock on the side against which he knew the door opened, and waited. In his youth he had learned the patience of the red Indian which transcends even the patience of the East. For an hour he stood there, scarcely moving a muscle. A statue could hardly have stood more immobilely.