El Borak and Other Desert Adventures (6 page)

Read El Borak and Other Desert Adventures Online

Authors: Robert E. Howard

As he approached the house, he saw someone running toward him. It was

Bardylis, and he threw himself on Gordon with a cry of relief that was not feigned.

“Oh, my brother!” he exclaimed. “What has happened? I found your chamber empty a short time ago, and blood on your couch. Are you unhurt? Nay, there is a cut upon your scalp!”

Gordon explained in a few words, saying nothing of the letters. He allowed Bardylis to suppose that Abdullah had been a personal enemy, bent on revenge. He trusted the youth now, but there was no need to disclose the truth of the packet.

Bardylis whitened with fury. “What a shame upon my house!” he cried. “Last night that dog Abdullah made my father a present of a great jug of wine, and we all drank except yourself, who were slumbering. I know now the wine was drugged. We slept like dogs.

“Because you were our guest, I posted a man at each outer door last night, but they fell asleep because of the wine they had drunk. A few minutes ago, searching for you, I found the servant who was posted at the door which opens into this alley from the corridor that runs past your chamber. His throat had been cut. It was easy for them to creep along that corridor and into your chamber while we slept.”

Back in the chamber, while Bardylis went to fetch fresh garments, Gordon retrieved the packet from the wall and stowed it under his belt. In his waking hours he preferred to keep it on his person.

Bardylis returned then with the breeches, sandals and tunic of the Attalans, and while Gordon donned them, gazed in admiration at the American’s bronzed and sinewy torso, devoid as it was of the slightest trace of surplus flesh.

Gordon had scarcely completed his dressing when voices were heard without, the tramp of men resounded through the hall, and a group of yellow-haired warriors appeared at the doorway, with swords at their sides. Their leader pointed to Gordon, and said: “Ptolemy commands that this man appear at once before him, in the hall of justice.”

“What is this?” exclaimed Bardylis. “El Borak is my guest!”

“It is not my part to say,” answered the chief. “I but carry out the commands of our king.”

Gordon laid a restraining hand on Bardylis’s arm. “I will go. I want to see what business Ptolemy has with me.”

“I, too, will go,” said Bardylis, with a snap of his jaws. “What this portends I do not know. I do know that El Borak is my friend.”

The sun was not yet rising as they strode down the white street toward the palace, but people were already moving about, and many of them followed the procession.

Mounting the broad steps of the palace, they entered a wide hall, flanked with lofty columns. At the other end there were more steps, wide and curving, leading up to a dais on which, in a throne-like marble chair, sat the king of Attalus, sullen as ever. A number of his chiefs sat on stone benches on either side of the dais, and the common people ranged themselves along the wall, leaving a wide space clear before the throne.

In this open space crouched a vulture-like figure. It was Abdullah, his eyes shining with hate and fear, and before him lay the corpse of the man Gordon had killed in the deserted house. The other two kidnapers stood near by, their bruised features sullen and ill at ease.

Gordon was conducted into the open space before the dais, and the guards fell back on either side of him. There was little formality. Ptolemy motioned to Abdullah and said: “Make your charge.”

Abdullah sprang up and pointed a skinny finger in Gordon’s face.

“I accuse this man of murder!” he screeched. “This morning before dawn he attacked me and my friends while we slept, and slew him who lies there. The rest of us barely escaped with our lives!”

A mutter of surprize and anger rose from the throng. Ptolemy turned his somber stare on Gordon.

“What have you to say?”

“He lies,” answered the American impatiently. “I killed that man, yes —”

He was interrupted by a fierce cry from the people, who began to surge menacingly forward, to be thrust back by the guards.

“I only defended my life,” said Gordon angrily, not relishing his position of defendant. “That Tajik dog and three others, that dead man and those two standing there, slipped in my chamber last night as I slept in the house of Perdiccas, knocked me senseless and carried me away to rob and kill me.”

“Aye!” cried Bardylis wrathfully. “And they slew one of my father’s servants while he slept.”

At that the murmur of the mob changed, and they halted in uncertainty.

“A lie!” screamed Abdullah, fired to recklessness by avarice and hate. “Bardylis is bewitched! El Borak is a wizard! How else could he speak your tongue?”

The crowd recoiled abruptly, and some made furtive signs to avert conjury. The Attalans were as superstitious as their ancestors. Bardylis had drawn his sword, and his friends rallied about him, clean-cut, rangy youngsters, quivering like hunting dogs in their eagerness.

“Wizard or man!” roared Bardylis, “he is my brother, and no man touches him save at peril of his head!”

“He is a wizard!” screamed Abdullah, foam dabbling his beard. “I know him of old! Beware of him! He will bring madness and ruin upon Attalus! On

his body he bears a scroll with magic inscriptions, wherein lies his necromantic power! Give that scroll to me, and I will take it afar from Attalus and destroy it where it can do no harm. Let me prove I do not lie! Hold him while I search him, and I will show you.”

“Let no man dare touch El Borak!” challenged Bardylis. Then from his throne rose Ptolemy, a great menacing image of bronze, somber and awe-inspiring. He strode down the steps, and men shrank back from his bleak eyes. Bardylis stood his ground, as if ready to defy even his terrible king, but Gordon drew the lad aside. El Borak was not one to stand quietly by while someone else defended him.

“It is true,” he said without heat, “that I have a packet of papers in my garments. But it is also true that it has nothing to do with witchcraft, and that I will kill the man who tries to take it from me.”

At that Ptolemy’s brooding impassiveness vanished in a flame of passion.

“Will you defy even me?” he roared, his eyes blazing, his great hands working convulsively. “Do you deem yourself already king of Attalus? You black-haired dog, I will kill you with my naked hands! Back, and give us space!”

His sweeping arms hurled men right and left, and roaring like a bull, he hurled himself on Gordon. So swift and violent was his attack that Gordon was unable to avoid it. They met breast to breast, and the smaller man was hurled backward, and to his knee. Ptolemy plunged over him, unable to check his velocity, and then, locked in a death-grapple they ripped and tore, while the people surged yelling about them.

Not often did El Borak find himself opposed by a man stronger than himself. But the king of Attalus was a mass of whale-bone and iron, and nerved to blinding quickness. Neither had a weapon. It was man to man, fighting as the primitive progenitors of the race fought. There was no science about Ptolemy’s onslaught; he fought like a tiger or a lion, with all the appalling frenzy of the primordial. Again and again Gordon battered his way out of a grapple that threatened to snap his spine like a rotten branch. His blinding blows ripped and smashed in a riot of destruction. The tall king of Attalus swayed and trembled before them like a tree in a storm, but always came surging back like a typhoon, lashing out with great strokes that drove Gordon staggering before him, rending and tearing with mighty fingers.

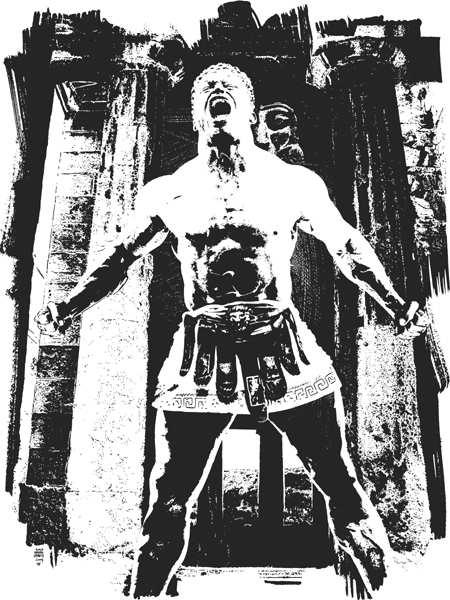

Only his desperate speed and the savage skill of boxing and wrestling that was his had saved Gordon so long. Naked to the waist, battered and bruised, his tortured body quivered with the punishment he was enduring. But Ptolemy’s great chest was heaving; his face was a mask of raw beef, and his torso showed the effects of a beating that would have killed a lesser man.

Gasping a cry that was half curse, half sob, he threw himself bodily on the American, bearing him down by sheer weight. As they fell he drove a knee

savagely at Gordon’s groin, and tried to fall with his full weight on the smaller man’s breast. A twist of his body sent the knee sliding harmlessly along his thigh, and Gordon writhed from under the heavier body as they fell.

The impact broke their holds, and they staggered up simultaneously. Through the blood and sweat that streamed into his eyes, Gordon saw the king towering above him, reeling, arms spread, blood pouring down his mighty breast. His belly went in as he drew a great laboring breath. And into the relaxed pit of his stomach Gordon, crouching, drove his left with all the strength of ridged arm, iron shoulders and knotted calves behind it. His clenched fist sank to the wrist in Ptolemy’s solar plexus. The king’s breath went out of him in an explosive grunt; his hands dropped, he swayed like a tall tree under the axe. Gordon’s right, hooking up in a terrible arc, met his jaw with a sound like a cooper’s mallet, and Ptolemy pitched headlong and lay still.

In the stupified silence that followed the fall of the king, while all eyes, dilated with surprize, were fixed on the prostrate giant and the groggy figure that weaved above him, a gasping voice shouted from outside the palace. It grew louder, mingled with a clatter of hoofs which stopped at the outer steps. All wheeled toward the door as a wild figure staggered in, spattering blood.

“A guard from the pass!” cried Bardylis.

“The Moslems!” cried the man, blood spurting through his fingers which he pressed to his shoulder. “Three hundred Afghans! They have stormed the pass! They are led by a

Feringhi

and four

Turki

who have rifles that fire many times without reloading! These men shot us down from afar off as we strove to defend the pass. The Afghans have entered the valley —” He swayed and fell, blood trickling from his lips. A blue bullet hole showed in his shoulder, near the base of his neck.

No clamor of terror greeted this appalling news. In the utter silence that followed, all eyes turned toward Gordon, leaning dizzily against the wall, gasping for breath.

“You have conquered Ptolemy,” said Bardylis. “He is dead or senseless. While he is helpless, you are king. That is the law. Tell us what to do.”

Gordon gathered his dazed wits and accepted the situation without demur or question. If the Afghans were in the valley, there was no time to waste. He thought he could hear the distant popping of firearms already.

“How many men are able to bear arms?” he panted.

“Three hundred and fifty,” answered one of the chiefs.

“Then let them take their weapons and follow me,” he said. “The walls of

the city are rotten. If we try to defend them, with Hunyadi directing the siege, we will be trapped like rats. We must win with one stroke, if at all.”

Someone brought him a sheathed and belted scimitar and he buckled it about his waist. His head was still swimming and his body numb, but from some obscure reservoir he drew a fund of reserve power, and the prospect of a final showdown with Hunyadi fired his blood. At his directions men lifted Ptolemy and placed him on a couch. The king had not moved since he dropped, and Gordon thought it probable that he had a concussion of the brain. That pole-ax smash that had felled him would have split the skull of a lesser man.

Then Gordon remembered Abdullah, and looked about for him, but the Tajik had vanished.

At the head of the warriors of Attalus, Gordon strode down the street and through the ponderous gate. All were armed with long curved swords; some had unwieldy matchlocks, ancient weapons captured from the hill tribes. He knew the Afghans would be no better armed, but the rifles of Hunyadi and his Turks would count heavily.

He could see the horde swarming up the valley, still some distance away. They were on foot. Lucky for the Attalans that one of the pass-guards had kept a horse near him. Otherwise the Afghans would have been at the very walls of the town before the word came of their invasion.

The invaders were drunk with exultation, halting to fire outlying huts and growing stuff, and to shoot cattle, in sheer wanton destructiveness. Behind Gordon rose a deep rumble of rage, and looking back at the blazing blue eyes, and tall, tense figures, the American knew he was leading no weaklings to battle.

He led them to a long straggling heap of stones which ran waveringly clear across the valley, marking an ancient fortification, long abandoned and crumbling down. It would afford some cover. When they reached it the invaders were still out of rifle fire. The Afghans had ceased their plundering and came on at an increased gait, howling like wolves.

Gordon ordered his men to lie down behind the stones, and called to him the warriors with the matchlocks — some thirty in all.

“Pay no heed to the Afghans,” he instructed them. “Shoot at the men with the rifles. Do not shoot at random, but wait until I give the word, then all fire together.”

The ragged horde were spreading out somewhat as they approached, loosing their matchlocks before they were in range of the grim band waiting silently along the crumbled wall. The Attalans quivered with eagerness, but Gordon gave no sign. He saw the tall, supple figure of Hunyadi, and the bulkier shapes of his turbaned Turks, in the center of the ragged crescent. The men came straight on, apparently secure in the knowledge that the Attalans had no modern weapons, and that Gordon had lost his rifle. They had

seen him climbing down the cliff without it. Gordon cursed Abdullah, whose treachery had lost him his pistol.