El Borak and Other Desert Adventures (66 page)

Read El Borak and Other Desert Adventures Online

Authors: Robert E. Howard

K

EY TO THE

T

REASURE

It was not mere impulsiveness that sent Kirby O’Donnell into the welter of writhing limbs and whickering blades that loomed so suddenly in the semidarkness ahead of him. In that dark alley of Forbidden Shahrazar it was no light act to plunge headlong into a nameless brawl; and O’Donnell, for all his Irish love of a fight, was not disposed thoughtlessly to jeopardize his secret mission.

But the glimpse of a scarred, bearded face swept from his mind all thought and emotion save a crimson wave of fury. He acted instinctively.

Full into the midst of the flailing group, half-seen by the light of a distant cresset, O’Donnell leaped,

kindhjal

in hand. He was dimly aware that one man was fighting three or four others, but all his attention was fixed on a single tall gaunt form, dim in the shadows. His long, narrow, curved blade licked venomously at this figure, ploughing through cloth, bringing a yelp as the edge sliced skin. Something crashed down on O’Donnell’s head, gun butt or bludgeon, and he reeled, his eyes full of sparks, and closed with someone he could not see.

His groping hand locked on a chain that encircled a bull neck, and with a straining gasp he ripped upward and felt his keen

kindhjal

slice through cloth, skin and belly muscles. An agonized groan burst from his victim’s lips, and blood gushed sickeningly over O’Donnell’s hand.

Through a blur of clearing sight, the American saw a broad bearded face falling away from him — not the face he had seen before. The next instant he had leaped clear of the dying man, and was slashing at the shadowy forms about him. An instant of flickering steel, and then the figures were running fleetly up the alley. O’Donnell, springing in pursuit, his hot blood lashed to murderous fury, tripped over a writhing form and fell headlong. He rose, cursing, and was aware of a man near him, panting heavily. A tall man, with a long curved blade in hand. Three forms lay in the mud of the alley.

“Come, my friend, whoever you are!” the tall man panted in

Turki

. “They have fled, but they will return with others. Let us go!”

O’Donnell made no reply. Temporarily accepting the alliance into which chance had cast him, he followed the tall stranger who ran down the winding alley with the sure foot of familiarity. Silence held them until they emerged from a low dark arch, where a tangle of alleys debouched upon a broad square, vaguely lighted by small fires about which groups of turbaned men squabbled and brewed tea. A reek of unwashed bodies mingled with the odors of horses and camels. None noticed the two men standing in the shadow made by the angle of the mud wall.

O’Donnell looked at the stranger, seeing a tall slim man with thin dark features. Under his

khalat

which was draggled and darkly splashed, showed the silver-heeled boots of a horseman. His turban was awry, and though he had sheathed his scimitar, blood clotted the hilt and the scabbard mouth.

The keen black eyes took in every detail of the American’s appearance, but O’Donnell did not flinch. His disguise had stood the test too many times for him to doubt its effectiveness.

The American was somewhat above medium height, leanly built, but with broad shoulders and corded sinews which gave him a strength out of all proportion to his weight. He was a hard-woven mass of wiry muscles and steel string nerves, combining the wolf-trap coordination of a natural fighter with a berserk fury resulting from an overflowing nervous energy. The

kindhjal

in his girdle and the scimitar at his hip were as much a part of him as his hands.

He wore the Kurdish boots, vest and girdled

khalat

like a man born to them. His keen features, burned to bronze by desert suns, were almost as dark as those of his companion.

“Tell me thy name,” requested the other. “I owe my life to thee.”

“I am Ali el Ghazi, a Kurd,” answered O’Donnell.

No hint of suspicion shadowed the other’s countenance. Under the coiffed Arab

kafiyeh

O’Donnell’s eyes blazed lambent blue, but blue eyes were not at all unknown among the warriors of the Iranian highlands.

The Turk lightly and swiftly touched the hawk-headed pommel of O’Donnell’s scimitar.

“I will not forget,” he promised. “I will know thee wherever we meet again. Now it were best we separated and went far from this spot, for men with knives will be seeking me — and thou too, for aiding me.” And like a shadow he glided among the camels and bales and was gone.

O’Donnell stood silently for an instant, one ear cocked back toward the alley, the other absently taking in the sounds of the night. Somewhere a thin wailing voice sang to a twanging native lute. Somewhere else a feline-like burst of profanity marked the progress of a quarrel. O’Donnell breathed deep with contentment, despite the grim Hooded Figure that stalked forever at his shoulder, and the recent rage that still seethed in his veins. This was the real heart of the East, the East which had long ago stolen his heart and led him to wander afar from his own people.

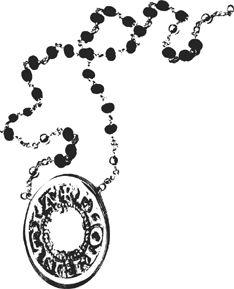

He realized that he still gripped something in his left hand, and he lifted it to the flickering light of a nearby fire. It was a length of gold chain, one of its massy links twisted and broken. From it depended a curious plaque of beaten gold, somewhat larger than a silver dollar, but oval rather than round. There was no ornament, only a boldly carven inscription which O’Donnell, with all his Eastern lore, could not decipher.

He knew that he had torn the chain from the neck of the man he had killed in that black alley, but he had no idea as to its meaning. Slipping it into his broad girdle, he strode across the square, walking with the swagger of a nomadic horseman that was so natural to him.

Leaving the square he strode down a narrow street, the overhanging balconies of which almost touched one another. It was not late. Merchants in flowing silk robes sat cross-legged before their booths, extolling the quality of their goods — Mosul silk, matchlocks from Herat, edged weapons from India, and seed pearls from Baluchistan. Hawk-like Afghans and weapon-girdled Uzbeks jostled him. Lights streamed through silk-covered windows overhead, and the light silvery laughter of women rose above the noise of barter and dispute.

There was a tingle in the realization that he, Kirby O’Donnell, was the first Westerner ever to set foot in Forbidden Shahrazar, tucked away in a nameless valley not many days’ journey from where the Afghan mountains swept down into the steppes of the Turkomans. As a wandering Kurd, traveling with a caravan from Kabul he had come, staking his life against the golden lure of a treasure beyond men’s dreams.

In the bazaars and

serais

he had heard a tale: To Shaibar Khan, the Uzbek chief who had made himself master of Shahrazar, the city had given up its ancient secret. The Uzbek had found the treasure hidden there so long ago by

Muhammad Shah, king of Khuwarezm, the Land of the Throne of Gold, when his empire fell before the Mongols.

O’Donnell was in Shahrazar to steal that treasure; and he did not change his plans because of the bearded face he had recognized in the alley — the face of an old and hated enemy: Yar Akbar the Afridi, traitor and murderer.

O’Donnell turned from the street and entered a narrow arched gate which stood open as if in invitation. A narrow stair went up from a small court to a balcony. This he mounted, guided by the tinkle of a guitar and a plaintive voice singing in

Pushtu

.

He entered a room whose latticed casement overhung the street, and the singer ceased her song to greet him and make half-mocking salaam with a lithe flexing of supple limbs. He replied, and deposited himself on a divan. The furnishings of the room were not elaborate, but they were costly. The garments of the woman who watched interestedly were of silk, her satin vest sewn with seed pearls. Her dark eyes, over the filmy

yasmaq

, were lustrous and expressive, the eyes of a Persian.

“Would my lord have food — and wine?” she inquired; and O’Donnell signified assent with the lordly gesture of a Kurdish swashbuckler who is careful not to seem too courteous to any woman, however famed in intrigue she may be. He had come there not for food and drink, but because he had heard in the bazaars that news of many kinds blew on the winds through the house of Ayisha, where men from far and near came to drink her wine and listen to her songs.

She served him, and, sinking down on cushions near him, watched him eat and drink. O’Donnell’s appetite was not feigned. Many lean days had taught him to eat when and where he could. Ayisha seemed to him more like a curious child than an intriguing woman, evincing so much interest over a wandering Kurd, but he knew that she was weighing him carefully behind her guileless stare, as she weighed all men who came into her house.

In that hot-bed of plot and ambitions, the wandering stranger today might be the Amir of Afghanistan or the Shah of Persia tomorrow — or the morrow might see his headless body dangling as a feast for the birds.

“You have a good sword,” said she. He involuntarily touched the hilt. It was an Arab blade, long, lean, curved like the crescent moon, with a brass hawk’s head for a pommel.

“It has cut many a Turkoman out of the saddle,” he boasted, with his mouth full, carrying out his character. Yet it was no empty boast.

“Hai!”

She believed him and was impressed. She rested her chin on her small fists and gazed up at him, as if his dark, hawk-like face had caught her fancy.

“The Khan needs swords like yours,” she said.

“The Khan has many swords,” he retorted, gulping wine loudly.

“No more than he will need if Orkhan Bahadur comes against him,” she prophesied.

“I have heard of this Orkhan,” he replied. And so he had; who in Central Asia had not heard of the daring and valorous Turkoman chief who defied the power of Moscow and had cut to pieces a Russian expedition sent to subdue him? “In the bazaars they say the Khan fears him.”

That was a blind venture. Men did not speak of Shaibar Khan’s fears openly.

Ayisha laughed. “Who does the Khan fear? Once the Amir sent troops to take Shahrazar, and those who lived were glad to flee! Yet if any man lives who could storm the city, Orkhan Bahadur is that man. Only tonight the Uzbeks were hunting his spies through the alleys.”

O’Donnell remembered the Turkish accent of the stranger he had unwittingly aided. It was quite possible that the man was a Turkoman spy.

As he pondered this, Ayisha’s sharp eyes discovered the broken end of the gold chain dangling from his girdle, and with a gurgle of delight she snatched it forth before he could stop her. Then with a squeal she dropped it as if it were hot, and prostrated herself in wriggling abasement among the cushions.

He scowled and picked up the trinket.

“Woman, what are you about?” he demanded.

“Your pardon, lord!” She clasped her hands, but her fear seemed more feigned than real; her eyes sparkled. “I did not know it was the token.

Aie

, you have been making game of me — asking me things none could know better than yourself. Which of the Twelve are you?”

“You babble as bees hum!” He scowled, dangling the pendant before her eyes. “You speak as one of knowledge, when, by Allah, you know not the meaning of this thing.”

“Nay, but I do!” she protested. “I have seen such emblems before on the breasts of the

emirs

of the Inner Chamber. I know that it is a

talsmin

greater than the seal of the Amir, and the wearer comes and goes at will in or out of the Shining Palace.”

“But why, wench, why?” he growled impatiently.