Eldritch Tales (37 page)

Authors: H.P. Lovecraft

The rapping was now repeated with greater insistence, and this time bore a hint of metal. The black thing facing me had become only a head with eyes, impotently trying to wriggle across the sinking floor in my direction, and occasionally emitting feeble little spits of immortal malice. Now swift and splintering blows assailed the sickly panels, and I saw the gleam of a tomahawk as it cleft the rending wood. I did not move, for I could not; but watched dazedly as the door fell in pieces to admit a colossal, shapeless influx of inky substance starred with shining, malevolent eyes. It poured thickly, like a flood of oil bursting a rotten bulkhead, overturned a chair as it spread, and finally flowed under the table and across the room to where the blackened head with the eyes still glared at me. Around that head it closed, totally swallowing it up, and in another moment it had begun to recede; bearing away its invisible burden without touching me, and flowing again out of that black doorway and down the unseen stairs, which creaked as before, though in reverse order.

Then the floor gave way at last, and I slid gaspingly down into the nighted chamber below, choking with cobwebs and half-swooning with terror. The green moon, shining through broken windows, shewed me the hall door half open; and as I rose from the plaster-strown floor and twisted myself free from the sagged ceilings, I saw sweep past it an awful torrent of blackness, with scores of baleful eyes glowing in it. It was seeking the door to the cellar, and when it found it, it vanished therein. I now felt the floor of this lower room giving as that of the upper chamber had done, and once a crashing above had been followed by the fall past the west window of something which must have been the cupola. Now liberated for the instant from the wreckage, I rushed through the hall to the front door; and finding myself unable to open it, seized a chair and broke a window, climbing frenziedly out upon the unkempt lawn where moonlight danced over yard-high grass and weeds. The wall was high, and all the gates were locked; but moving a pile of boxes in a corner I managed to gain the top and cling to the great stone urn set there.

About me in my exhaustion I could see only strange walls and windows and old gambrel roofs. The steep street of my approach was nowhere visible, and the little I did see succumbed rapidly to a mist that rolled in from the river despite the glaring moonlight. Suddenly the urn to which I clung began to tremble, as if sharing my own lethal dizziness; and in another instant my body was plunging downward to I knew not what fate.

The man who found me said that I must have crawled a long way despite my broken bones, for a trail of blood stretched off as far as he dared look. The gathering rain soon effaced this link with the scene of my ordeal, and reports could state no more than that I had appeared from a place unknown, at the entrance of a little black court off Perry Street.

I never sought to return to those tenebrous labyrinths, nor would I direct any sane man thither if I could. Of who or what that ancient creature was, I have no idea; but I repeat that the city is dead and full of unsuspected horrors. Whither

he

has gone, I do not know; but I have gone home to the pure New England lanes up which fragrant sea-winds sweep at evening.

FESTIVAL

T

HERE IS SNOW on the ground,

And the valleys are cold,

And a midnight profound

Blackly squats o’er the wold;

But a light on the hilltops half-seen hints of feastings unhallow’d and old.

There is death in the clouds,

There is fear in the night,

For the dead in their shrouds

Hail the sun’s turning flight,

And chant wild in the woods as they dance round a Yule-altar fungous and white.

To no gale of earth’s kind

Sways the forest of oak,

Where the sick boughs entwin’d

By mad mistletoes choke,

For these pow’rs are the pow’rs of the dark, from the graves of the lost Druid-folk.

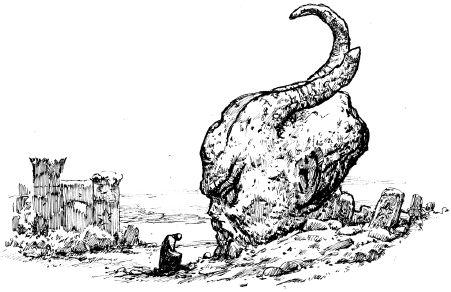

And mayst thou to such deeds

Be an abbot and priest,

Singing cannibal greeds

At each devil-wrought feast,

And to all the incredulous world shewing dimly the sign of the beast.

THE GREEN MEADOW

(

with Winifred Virginia Jackson

)

Translated by Elizabeth Neville Berkeley and Lewis Theobald, Jun.

I

NTRODUCTORY NOTE: The following very singular narrative or record of impressions was discovered under circumstances so extraordinary that they deserve careful description. On the evening of Wednesday, August 27, 1913, at about 8:30 o’clock, the population of the small seaside village of Potowonket, Maine, USA, was aroused by a thunderous report accompanied by a blinding flash; and persons near the shore beheld a mammoth ball of fire dart from the heavens into the sea but a short distance out, sending up a prodigious column of water. The following Sunday a fishing party composed of John Richmond, Peter B. Carr, and Simon Canfield caught in their trawl and dragged ashore a mass of metallic rock, weighing 360 pounds, and looking (as Mr Canfield said) like a piece of slag. Most of the inhabitants agreed that this heavy body was none other than the fireball which had fallen from the sky four days before; and Dr Richmond M. Jones, the local scientific authority, allowed that it must be an aerolite or meteoric stone. In chipping off specimens to send to an expert Boston analyst, Dr Jones discovered imbedded in the semi-metallic mass the strange book containing the ensuing tale, which is still in his possession.

In form the discovery resembles an ordinary notebook, about

5

x

3

inches in size, and containing thirty leaves. In material, however, it presents marked peculiarities. The covers are apparently of some dark stony substance unknown to geologists, and unbreakable by any mechanical means. No chemical reagent seems to act upon them. The leaves are much the same, save that they are lighter in colour, and so infinitely thin as to be quite flexible. The whole is bound by some process not very clear to those who have observed it; a process involving the adhesion of the leaf substance to the cover substance. These substances cannot now be separated, nor can the leaves be torn by any amount of force. The writing is

Greek of the purest classical quality,

and several students of palaeography declare that the characters are in a cursive hand used about the second century

BC

. There is little in the text to determine the date. The mechanical mode of writing cannot be deduced beyond the fact that it must have resembled that of the modern slate and slate-pencil. During the course of analytical efforts made by the late Prof. Chambers of Harvard, several pages, mostly at the conclusion of the narrative, were blurred to the point of utter effacement before being read; a circumstance forming a well-nigh irreparable loss. What remains of the contents was done into modern Greek letters by the palaeographer Rutherford and in this form submitted to the translators.

Prof. Mayfield of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who examined samples of the strange stone, declares it a true meteorite; an opinion in which Dr. von Winterfeldt of Heidelberg (interned in 1918 as a dangerous enemy alien) does not concur. Prof. Bradley of Columbia College adopts a less dogmatic ground; pointing out that certain utterly unknown ingredients are present in large quantities, and warning that no classification is as yet possible.

The presence, nature, and message of the strange book form so momentous a problem, that no explanation can even be attempted. The text, as far as preserved, is here rendered as literally as our language permits, in the hope that some reader may eventually hit upon an interpretation and solve one of the greatest scientific mysteries of recent years.

—E.N.B.–L.T., Jun.

(The Story)

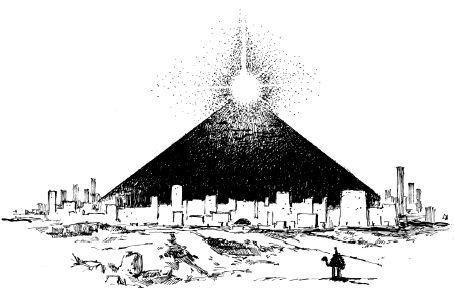

I

T WAS A NARROW PLACE, and I was alone. On one side, beyond a margin of vivid waving green, was the sea; blue, bright, and billowy, and sending up vaporous exhalations which intoxicated me. So profuse, indeed, were these exhalations, that they gave me an odd impression of a coalescence of sea and sky; for the heavens were likewise bright and blue. On the other side was the forest, ancient almost as the sea itself, and stretching infinitely inland. It was very dark, for the trees were grotesquely huge and luxuriant, and incredibly numerous. Their giant trunks were of a horrible green which blended weirdly with the narrow green tract whereon I stood. At some distance away, on either side of me, the strange forest extended down to the water’s edge; obliterating the shore line and completely hemming in the narrow tract. Some of the trees, I observed, stood in the water itself; as though impatient of any barrier to their progress.