Eldritch Tales (55 page)

Authors: H.P. Lovecraft

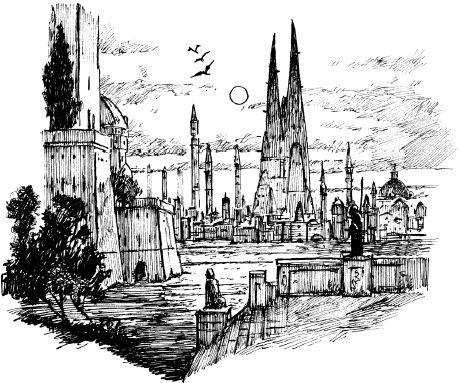

I never can be tied to raw, new things,

For I first saw the light in an old town,

Where from my window huddled roofs sloped down

To a quaint harbour rich with visionings.

Streets with carved doorways where the sunset beams

Flooded old fanlights and small window-panes,

And Georgian steeples topped with gilded vanes—

These were the sights that shaped my childhood dreams.

Such treasures, left from times of cautious leaven,

Cannot but loose the hold of flimsier wraiths

That flit with shifting ways and muddled faiths

Across the changeless walls of earth and heaven.

They cut the moment’s thongs and leave me free

To stand alone before eternity.

31. The Dweller

It had been old when Babylon was new;

None knows how long it slept beneath that mound,

Where in the end our questing shovels found

Its granite blocks and brought it back to view.

There were vast pavements and foundation-walls,

And crumbling slabs and statues, carved to shew

Fantastic beings of some long ago

Past anything the world of man recalls.

And then we saw those stone steps leading down

Through a choked gate of graven dolomite

To some black haven of eternal night

Where elder signs and primal secrets frown.

We cleared a path – but raced in mad retreat

When from below we heard those clumping feet.

32. Alienation

His solid flesh had never been away,

For each dawn found him in his usual place,

But every night his spirit loved to race

Through gulfs and worlds remote from common day.

He had seen Yaddith, yet retained his mind,

And come back safely from the Ghooric zone,

When one still night across curved space was thrown

That beckoning piping from the voids behind.

He waked that morning as an older man,

And nothing since has looked the same to him.

Objects around float nebulous and dim—

False, phantom trifles of some vaster plan.

His folk and friends are now an alien throng

To which he struggles vainly to belong.

33. Harbour Whistles

Over old roofs and past decaying spires

The harbour whistles chant all through the night;

Throats from strange ports, and beaches far and white,

And fabulous oceans, ranged in motley choirs.

Each to the other alien and unknown,

Yet all, by some obscurely focussed force

From brooding gulfs beyond the Zodiac’s course,

Fused into one mysterious cosmic drone.

Through shadowy dreams they send a marching line

Of still more shadowy shapes and hints and views;

Echoes from outer voids, and subtle clues

To things which they themselves cannot define.

And always in that chorus, faintly blent,

We catch some notes no earth-ship ever sent.

34. Recapture

The way led down a dark, half-wooded heath

Where moss-grey boulders humped above the mould,

And curious drops, disquieting and cold,

Sprayed up from unseen streams in gulfs beneath.

There was no wind, nor any trace of sound

In puzzling shrub, or alien-featured tree,

Nor any view before – till suddenly,

Straight in my path, I saw a monstrous mound.

Half to the sky those steep sides loomed upspread,

Rank-grassed, and cluttered by a crumbling flight

Of lava stairs that scaled the fear-topped height

In steps too vast for any human tread.

I shrieked – and

knew

what primal star and year

Had sucked me back from man’s dream-transient sphere!

35. Evening Star

I saw it from that hidden, silent place

Where the old wood half shuts the meadow in.

It shone through all the sunset’s glories – thin

At first, but with a slowly brightening face.

Night came, and that lone beacon, amber-hued,

Beat on my sight as never it did of old;

The evening star – but grown a thousandfold

More haunting in this hush and solitude.

It traced strange pictures on the quivering air—

Half-memories that had always filled my eyes—

Vast towers and gardens; curious seas and skies

Of some dim life – I never could tell where.

But now I knew that through the cosmic dome

Those rays were calling from my far, lost home.

36. Continuity

There is in certain ancient things a trace

Of some dim essence – more than form or weight;

A tenuous aether, indeterminate,

Yet linked with all the laws of time and space.

A faint, veiled sign of continuities

That outward eyes can never quite descry;

Of locked dimensions harbouring years gone by,

And out of reach except for hidden keys.

It moves me most when slanting sunbeams glow

On old farm buildings set against a hill,

And paint with life the shapes which linger still

From centuries less a dream than this we know.

In that strange light I feel I am not far

From the fixt mass whose sides the ages are.

Dec. 27, 1929–Jan. 4, 1930.

THE TRAP

(

with Henry S. Whitehead

)

I

T WAS ON A CERTAIN Thursday morning in December that the whole thing began with that unaccountable motion I thought I saw in my antique Copenhagen mirror. Something, it seemed to me, stirred – something reflected in the glass, though I was alone in my quarters. I paused and looked intently, then, deciding that the effect must be a pure illusion, resumed the interrupted brushing of my hair.

I had discovered the old mirror, covered with dust and cobwebs, in an outbuilding of an abandoned estate-house in Santa Cruz’s sparsely settled Northside territory, and had brought it to the United States from the Virgin Islands. The venerable glass was dim from more than two hundred years’ exposure to a tropical climate, and the graceful ornamentation along the top of the gilt frame had been badly smashed. I had had the detached pieces set back into the frame before placing it in storage with my other belongings.

Now, several years later, I was staying half as a guest and half as a tutor at the private school of my old friend Browne on a windy Connecticut hillside – occupying an unused wing in one of the dormitories, where I had two rooms and a hallway to myself. The old mirror, stowed securely in mattresses, was the first of my possessions to be unpacked on my arrival; and I had set it up majestically in the living-room, on top of an old rosewood console which had belonged to my great-grandmother.

The door of my bedroom was just opposite that of the living-room, with a hallway between; and I had noticed that by looking into my chiffonier glass I could see the larger mirror through the two doorways – which was exactly like glancing down an endless, though diminishing, corridor. On this Thursday morning I thought I saw a curious suggestion of motion down that normally empty corridor – but, as I have said, soon dismissed the notion.

When I reached the dining-room I found everyone complaining of the cold, and learned that the school’s heating-plant was temporarily out of order. Being especially sensitive to low temperatures, I was myself an acute sufferer; and at once decided not to brave any freezing schoolroom that day. Accordingly I invited my class to come over to my living-room for an informal session around my grate-fire – a suggestion which the boys received enthusiastically.

After the session one of the boys, Robert Grandison, asked if he might remain; since he had no appointment for the second morning period. I told him to stay, and welcome. He sat down to study in front of the fireplace in a comfortable chair.

It was not long, however, before Robert moved to another chair somewhat farther away from the freshly replenished blaze, this change bringing him directly opposite the old mirror. From my own chair in another part of the room I noticed how fixedly he began to look at the dim, cloudy glass, and, wondering what so greatly interested him, was reminded of my own experience earlier that morning. As time passed he continued to gaze, a slight frown knitting his brows.

At last I quietly asked him what had attracted his attention. Slowly, and still wearing the puzzled frown, he looked over and replied rather cautiously:

‘It’s the corrugations in the glass – or whatever they are, Mr Canevin. I was noticing how they all seem to run from a certain point. Look – I’ll show you what I mean.’

The boy jumped up, went over to the mirror, and placed his finger on a point near its lower left-hand corner.

‘It’s right here, sir,’ he explained, turning to look toward me and keeping his finger on the chosen spot.

His muscular action in turning may have pressed his finger against the glass. Suddenly he withdrew his hand as though with some slight effort, and with a faintly muttered ‘Ouch.’ Then he looked at the glass in obvious mystification.

‘What happened?’ I asked, rising and approaching.

‘Why – it—’ He seemed embarrassed. ‘It – I – felt – well, as though it were pulling my finger into it. Seems – er – perfectly foolish, sir, but – well – it was a most peculiar sensation.’ Robert had an unusual vocabulary for his fifteen years.

I came over and had him show me the exact spot he meant.

‘You’ll think I’m rather a fool, sir,’ he said shamefacedly, ‘but – well, from right here I can’t be absolutely sure. From the chair it seemed to be clear enough.’

Now thoroughly interested, I sat down in the chair Robert had occupied and looked at the spot he selected on the mirror. Instantly the thing ‘jumped out at me’. Unmistakably, from that particular angle, all the many whorls in the ancient glass appeared to converge like a large number of spread strings held in one hand and radiating out in streams.

Getting up and crossing to the mirror, I could no longer see the curious spot. Only from certain angles, apparently, was it visible. Directly viewed, that portion of the mirror did not even give back a normal reflection – for I could not see my face in it. Manifestly I had a minor puzzle on my hands.