Eldritch Tales (62 page)

Authors: H.P. Lovecraft

Of this evil meddling the only bad result was that the worm-like outside race learned from the new exiles what had happened to their explorers on earth, and conceived a violent hatred of the planet and all its life-forms. They would have depopulated it if they could, and indeed sent additional cubes into space in the wild hope of striking it by accident in unguarded places – but that accident never came to pass.

The cone-shaped terrestrial beings kept the one existing cube in a special shrine as a relique and basis for experiments, till after aeons it was lost amidst the chaos of war and the destruction of the great polar city where it was guarded. When, fifty million years ago, the beings sent their minds ahead into the infinite future to avoid a nameless peril of inner earth, the whereabouts of the sinister cube from space were unknown.

This much, according to the learned occultist, the Eltdown Shards had said. What now made the account so obscurely frightful to Campbell was the minute accuracy with which the alien cube had been described. Every detail tallied – dimensions, consistency, hieroglyphed central disc, hypnotic effects. As he thought the matter over and over amidst the darkness of his strange situation, he began to wonder whether his whole experience with the crystal cube – indeed, its very existence – were not a nightmare brought on by some freakish subconscious memory of this old bit of extravagant, charlatanic reading. If so, though, the nightmare must still be in force; since his present apparently bodiless state had nothing of normality in it.

Of the time consumed by this puzzled memory and reflection, Campbell could form no estimate. Everything about his state was so unreal that ordinary dimensions and measurements became meaningless. It seemed an eternity, but perhaps it was not really long before the sudden interruption came. What happened was as strange and inexplicable as the blackness it succeeded. There was a sensation – of the mind rather than of the body – and all at once Campbell felt his thoughts swept or sucked beyond his control in tumultuous and chaotic fashion. Memories arose irresponsibly and irrelevantly. All that he knew – all his personal background, traditions, experiences, scholarship, dreams, ideas, and inspirations – welled up abruptly and simultaneously, with a dizzying speed and abundance which soon made him unable to keep track of any separate concept. The parade of all his mental contents became an avalanche, a cascade, a vortex. It was as horrible and vertiginous as his hypnotic flight through space when the crystal cube pulled him. Finally it sapped his consciousness and brought on fresh oblivion.

Another measureless blank – and then a slow trickle of sensations. This time it was physical, not mental. Sapphire light, and a low rumble of distant sound. There were tactile impressions – he could realise that he was lying at full length on something, though there was a baffling strangeness about the feel of his posture. He could not reconcile the pressure of the supporting surface with his own outlines – or with the outlines of the human form at all. He tried to move his arms, but found no definite response to the attempt. Instead, there were little, ineffectual nervous twitches all over the area which seemed to mark his body.

He tried to open his eyes more widely, but found himself unable to control their mechanism. The sapphire light came in a diffused, nebulous manner, and could nowhere be voluntarily focussed into definiteness. Gradually, though, visual images began to trickle in curiously and indecisively. The limits and qualities of vision were not those which he was used to, but he could roughly correlate the sensation with what he had known as sight. As this sensation gained some degree of stability, Campbell realised that he must still be in the throes of nightmare.

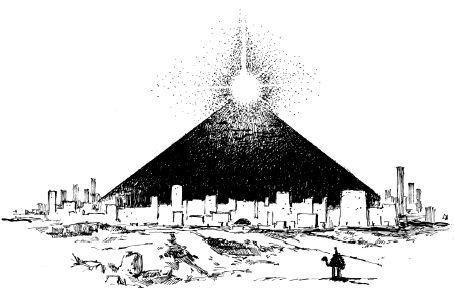

He seemed to be in a room of considerable extent – of medium height, but with a large proportionate area. On every side – and he could apparently see all four sides at once – were high, narrowish slits which seemed to serve as combined doors and windows. There were singular low tables or pedestals, but no furniture of normal nature and proportions. Through the slits streamed floods of sapphire light, and beyond them could be mistily seen the sides and roofs of fantastic buildings like clustered cubes. On the walls – in the vertical panels between the slits – were strange markings of an oddly disquieting character. It was some time before Campbell understood why they disturbed him so – then he saw that they were, in repeated instances, precisely like some of the hieroglyphs on the disc within the crystal cube.

The actual nightmare element, though, was something more than this. It began with the living thing which presently entered through one of the slits, advancing deliberately toward him and bearing a metal box of bizarre proportions and glassy, mirror-like surfaces. For this thing was nothing human – nothing of earth – nothing even of man’s myths and dreams. It was a gigantic, pale-grey worm or centipede, as large around as a man and twice as long, with a disc-like, apparently eyeless, cilia-fringed head bearing a purple central orifice. It glided on its rear pairs of legs, with its fore part raised vertically – the legs, or at least two pairs of them, serving as arms. Along its spinal ridge was a curious purple comb, and a fan-shaped tail of some grey membrane ended its grotesque bulk. There was a ring of flexible red spikes around its neck, and from the twistings of these came clicking, twanging sounds in measured, deliberate rhythms.

Here, indeed, was outré nightmare at its height – capricious fantasy at its apex. But even this vision of delirium was not what caused George Campbell to lapse a third time into unconsciousness. It took one more thing – one final, unbearable touch – to do that. As the nameless worm advanced with its glistening box, the reclining man caught in the mirror-like surface a glimpse of what should have been his own body. Yet – horribly verifying his disordered and unfamiliar sensations – it was not his own body at all that he saw reflected in the burnished metal. It was, instead, the loathsome, pale-grey bulk of one of the great centipedes.

IN A SEQUESTER’D PROVIDENCE CHURCHYARD WHERE ONCE POE WALK’D

E

TERNAL BROOD the shadows on this ground,

Dreaming of centuries that have gone before;

Great elms rise solemnly by slab and mound,

Arch’d high above a hidden world of yore.

Round all the scene a light of memory plays,

And dead leaves whisper of departed days,

Longing for sights and sounds that are no more.

Lonely and sad, a spectre glides along

Aisles where of old his living footsteps fell;

No common glance discerns him, tho’ his song

Peals down thro’ time with a mysterious spell:

Only the few who sorcery’s secret know

Espy amidst these tombs the shade of Poe.

IBID

(‘ . . . as Ibid says in his famous

Lives of the Poets

.’—

From a student theme

.)

T

HE ERRONEOUS IDEA that Ibid is the author of the

Lives

is so frequently met with, even among those pretending to a degree of culture, that it is worth correcting. It should be a matter of general knowledge that Cf. is responsible for this work. Ibid’s masterpiece, on the other hand, was the famous

Op

.

Cit

. wherein all the significant undercurrents of Graeco-Roman expression were crystallised once for all – and with admirable acuteness, notwithstanding the surprisingly late date at which Ibid wrote. There is a false report – very commonly reproduced in modern books prior to Von Schweinkopf’s monumental

Geschichte der Ostrogothen in Italien

– that Ibid was a Romanised Visigoth of Ataulf’s horde who settled in Placentia about

AD

410. The contrary cannot be too strongly emphasised; for Von Schweinkopf, and since his time Littlewit

1

and Bêtenoir,

2

have shewn with irrefutable force that this strikingly isolated figure was a genuine Roman – or at least as genuine a Roman as that degenerate and mongrelised age could produce – of whom one might well say what Gibbon said of Boethius, ‘that he was the last whom Cato or Tully could have acknowledged for their countryman.’ He was, like Boethius and nearly all the eminent men of his age, of the great Anician family, and traced his genealogy with much exactitude and self-satisfaction to all the heroes of the republic. His full name – long and pompous according to the custom of an age which had lost the trinomial simplicity of classic Roman nomenclature – is stated by Von Schweinkopf

3

to have been Caius Anicius Magnus Furius Camillus Aemilianus Cornelius Valerius Pompeius Julius Ibidus; though Littlewit

4

rejects

Aemilianus

and adds

Claudius Decius Junianus

, whilst Bêtenoir

5

differs radically, giving the full name as Magnus Furius Camillus Aurelius Antoninus Flavius Anicius Petronius Valentinianus Aegidus Ibidus.

The eminent critic and biographer was born in the year 486, shortly after the extinction of the Roman rule in Gaul by Clovis. Rome and Ravenna are rivals for the honour of his birth, though it is certain that he received his rhetorical and philosophical training in the schools of Athens – the extent of whose suppression by Theodosius a century before is grossly exaggerated by the superficial. In 512, under the benign rule of the Ostrogoth Theodoric, we behold him as a teacher of rhetoric at Rome, and in 516 he held the consulship together with Pompilius Numantius Bombastes Marcellinus Deodamnatus. Upon the death of Theodoric in 526, Ibidus retired from public life to compose his celebrated work (whose pure Ciceronian style is as remarkable a case of classic atavism as is the verse of Claudius Claudianus, who flourished a century before Ibidus); but he was later recalled to scenes of pomp to act as court rhetorician for Theodatus, nephew of Theodoric.

Upon the usurpation of Vitiges, Ibidus fell into disgrace and was for a time imprisoned; but the coming of the Byzantine-Roman army under Belisarius soon restored him to liberty and honours. Throughout the siege of Rome he served bravely in the army of the defenders, and afterward followed the eagles of Belisarius to Alba, Porto, and Centumcellae. After the Frankish siege of Milan, Ibidus was chosen to accompany the learned Bishop Datius to Greece, and resided with him at Corinth in the year 539. About 541 he removed to Constantinopolis, where he received every mark of imperial favour both from Justinianus and Justinus the Second. The Emperors Tiberius and Maurice did kindly honour to his old age, and contributed much to his immortality – especially Maurice, whose delight it was to trace his ancestry to old Rome notwithstanding his birth at Arabiscus, in Cappadocia. It was Maurice who, in the poet’s 101st year, secured the adoption of his work as a textbook in the schools of the empire, an honour which proved a fatal tax on the aged rhetorician’s emotions, since he passed away peacefully at his home near the church of St Sophia on the sixth day before the Kalends of September,

AD

587, in the 102nd year of his age.