Eleanor and Franklin (158 page)

Read Eleanor and Franklin Online

Authors: Joseph P. Lash

“Is there anything

we

can do for

you

?” she asked. “For you are the one in trouble now.”

As the arrangements went forward to swear in the vice president, he asked Eleanor whether there was anything she needed to have done. She told him she would like to go to Warm Springs at once and asked if it would be proper for her to make use of a government plane. He agreed immediately, and minutes after the new president was sworn in, she left for Warm Springs. As she walked, tall and erect, to the White House limousine, a group of newspaperwomen were standing beneath the portico. “A trouper to the last,” one of them whispered.

She was completely composed when she arrived at Warm Springs just before midnight. She swiftly embraced Laura Delano and Margaret Suckley and kissed Grace Tully, who murmured how deeply sorry she was for Eleanor and the children. “Tully, dear,” she replied, “I am so very sorry for all of you.” She sat down on the sofa and asked Laura and Margaret to tell her exactly what had happened. She listened quietly, exchanged a few words, and then went into the bedroom where her husband lay. She closed the door and remained inside for about five minutes. “When she came out her eyes were dry again, her face grave but composed,” Grace Tully wrote.

23

She then heard from Laura that Lucy Rutherfurd had been there when the president had died. She had come on April 9 from Aiken, bringing with her Mme. Shoumatoff to do a portrait of the president. Mrs. Rutherfurd, she also learned from Laura, had been to dinner at the White House, when Eleanor was away. Anna had been present as hostess, and Laura and Daisy had been there too.

24

How did she respond to that bitter discovery? Was it another dark night of the soul for her? She gave no outward sign of anger or hurt, and she did not mention Mrs. Rutherfurd's presence at Warm Springs when she came to write her account of the White House years in

This I Remember

. And yet the concluding paragraphs of her book unmistakably refer to it. She was accounting for the “almost impersonal feeling” that she had during the days after Franklin's death; she could not think of it as a personal sorrow: “It was the sorrow of all those to whom the man who now lay dead, and who happened to be my husband, had been a symbol of strength and fortitude.” Partly it was a protective device. From the time the war began she had been schooling herself

to the thought that some or all of her sons might be killed and that her husband might die.

But that did not wholly explain her feelings, she went on:

Perhaps it was much further back I had had to face certain difficulties until I decided to accept the fact that a man must be what he is, life must be lived as it is, circumstances force your children away from you, and you cannot live at all if you do not learn to adapt yourself to your life as it happens to be.

All human beings have failings, all human beings have needs and temptations and stresses. Men and women who live together through long years get to know one another's failings; but they also come to know what is worthy of respect and admiration in those they live with and in themselves. If at the end one can say: “This man used to the limit the powers that God granted him; he was worthy of love and respect and of the sacrifices of many people, made in order that he might achieve what he deemed to be his task,” then that life has been lived well and there are no regrets.

He might have been happier with a wife who was completely uncritical. That I was never able to be, and he had to find it in some other people. Nevertheless, I think I sometimes acted as a spur, even though the spurring was not always wanted or welcome. I was one of those who served his purposes.

25

As the funeral train moved north to Washington, she remained alone for most of the long, sad journey. Even after darkness fell,

I lay in my berth all night with the window shade up, looking out at the countryside he had loved and watching the faces of the people at stations, and even at the crossroads, who came to pay their last tribute all through the night.

The only recollection I clearly have is thinking about “The Lonesome train,” the musical poem about Lincoln's death. [“A lonesome train on a lonesome track / Seven coaches painted black / A slow train, a quiet train / Carrying Lincoln home again . . . ”] I had always liked it so wellâand now this was so much like it.

26

In Washington the funeral cortege with the black-draped caisson drawn by six white horses moved in slow, solemn processional toward the White House. When it arrived under the portico, a squad

of service men lifted the coffin from the caisson and carried it up the steps into the White House. Immediately behind it walked Eleanor, alone, leading her children. And at the funeral service in the East Room, reporters noted that she was wearing one piece of jewelry on her widow's weeds as she walked down the center aisle followed by her children. It was the small golden pin shaped like a fleur de lys that her husband had given her as a wedding gift.

Was she still in love with him? She told friends that she had not been, not since her discovery of the Lucy Mercer affair, but that she had given her husband a service of love because of her respect for his leadership and faith in his goals. “That is what she told me,” Esther Lape said. “That was her story. Maybe she even half believed it. But I didn't. I don't think she ever stopped loving someone she loved.”

27

And then Esther, unaware that her old friend had once responded to Franklin's proposal of marriage with the same lines from Elizabeth Barrett Browning, recited from memory:

Unless you can think when the song is done

No other is left in the rhythm;

Unless you can feel when left by one,

That all men else go with him;

Unless you can know when upraised by his breath,

That your beauty itself wants proving;

Unless you can swear, “For life, for death!”

Oh, fear to call it loving!

Â

*

A statement issued at the White House in Roosevelt's name said:

Memories of more than a score of years of devoted service enhance the sense of personal loss which Miss LeHand's passing brings. Faithful and painstaking, with a charm of manner in speech, by tact and kindness of heart, she was utterly selfless in her devotion to duty. Hers was a quiet efficiency, which made her a real genius at getting things done.

How much Roosevelt valued Missy was shown by his will when it was filed for probate after his death. It provided that Missy's medical expenses should be taken care of out of the income from his estate up to 50 per cent, the remainder going to Eleanor.

â

David Lilienthal recorded in his diary in 1953 a discussion about Yalta at J. J. Singh's where Eleanor was a guest, as were Lin Yutang, Anne O'Hare McCormick, Louis Fischer, and Walter White. “When Franklin came back from Yalta,” Eleanor began, and, noted Lilienthal, the whole chattering table immediately grew quiet,

I told him how disappointed I was, and rather shocked, that Esthonia, Lithuania, and Latvia had been left with the Soviet Union, upon Stalin's insistence, instead of being given their independence and freedom.

Franklin saidânow mind you I don't say he was right or wrong, but this shows the reasoning he had in his mindâFranklin said (and I can still see his face as he said it) he had thought about this for a long time. He asked me: “How many people in the United States do you think would be willing to go to war to free Esthonia, Latvia, and Lithuania?” I said I didn't suppose there would be very many. “Well,” he said, “if I had insisted on their being freed I would have had to consider what I would do to back up that decision, which might require war. And I concluded that the American people did not care enough about the freedom of those countries to go to war about it.”

Eleanor (right) with her father and two brothers, Elliott and Hall, taken about 1892.

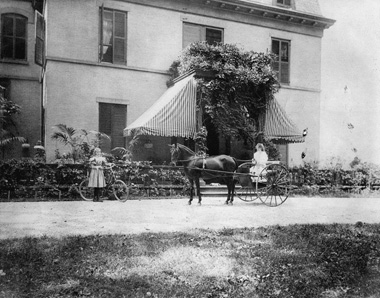

After her parents' deaths, Eleanor lived with her grandmother, Mrs. Hall, at Tivoli overlooking the Hudson. Here she is shown with her Aunt Maude, youngest of the beautiful Hall sisters.

The headmistress of Allenswood, Mlle. Souvestre, was at home in the worlds of high politics and high culture, and under her tutelage Eleanor blossomed.

In 1903 Eleanor and Franklin became secretly engaged. Here they are sitting on the porch of Sara's house at Campobello during Eleanor's visit in the summer of 1904.

Eleanor with Franklin's mother, Sara Delano Roosevelt, a daunting and remarkable woman. About 1904.