EllRay Jakes Is Not a Chicken (5 page)

Read EllRay Jakes Is Not a Chicken Online

Authors: Sally Warner

I think some peopleâ

especially

kidsâare mean for no reason.

especially

kidsâare mean for no reason.

What about when a mean person shoves someone in the hall? Or “accidentally” knocks the back of that person's head when he is drinking at the water fountain? Or grabs his lunch and plays keep-away with it?

That person does it because he can.

But I don't tell my mom that, because it would only make her sad. Even though she likes to write books about pretend-wonderful things that could have happened in a long-ago time, in real life she is a little bit of a worrywart when it comes to Alfie and me. She wants us never to get hurt.

Just as I think this thought, Mom pops her head around the door to my bedroom. “Can I tuck you in, EllRay?” she asks, smiling.

“Sure,” I tell her, scootching over in bed to make room for her to sit next to me. “Good,” my mom says, settling in for a before-bedtime visit, which is secretly one of my favorite things, because:

1. It's not like when I'm at school, where I can never really relax because I don't know what's gonna happen next.

2. And it's not like when I'm with Alfie, where I always have to watch her to make sure she doesn't try to fly down the stairs or something crazy like that.

3. And it's not like when I'm with my dad, where he is either trying to keep me from messing up in the future or scolding me for messing up in the past. Sometimes I think I must be a disappointment to him, he is so important and smart. And strong. And tall.

It's different with my mom. My mom is usually a very relaxing person, and she likes me no matter what. She even likes the

old

EllRay Jakes.

old

EllRay Jakes.

“Your daddy told me about your Disneyland deal,” Mom says, arranging my covers more neatly under my chin. “I guess you're pretty happy about that, hmm?”

“Yeah,” I say. “If I don't mess it up for everyone. Don't tell Alfie about it yet, okay? Just in case.”

“Okay,” Mom promises. “But I know you can do it, honey bun.”

“It'sâit's kind of like a bribe, though, isn't it?” I ask. “Us getting to go to Disneyland, but only if I'm good. And I thought you guys said that bribing people was wrong. Even bribing

kids

.”

kids

.”

My mom laughs a little. “I might have handled things differently,” she says quietly. “But whatever works, EllRayâbecause I want everyone at Oak Glen Primary School to see the same wonderful boy I see whenever I look at you.”

“I'm not

always

wonderful,” I admit in the dark.

always

wonderful,” I admit in the dark.

“To me you are,” Mom says. “Deep down inside. Butâwhat's going on?”

“Like, in the

world

?” I ask, pretending I don't know what she means.

world

?” I ask, pretending I don't know what she means.

“Not in

the

world,” she says. “Just in

your

world.”

the

world,” she says. “Just in

your

world.”

“My world's fine,” I lie.

But it's the kind of lie that is meant to keep someone from feeling bad, like if a person asks, “

How does my new haircut look

?” and you say, “

Perfectly normal

,” instead of “

Like somebody went after you with broken kindergarten scissors

.”

How does my new haircut look

?” and you say, “

Perfectly normal

,” instead of “

Like somebody went after you with broken kindergarten scissors

.”

“Oh, come on,” Mom says in her softest voice. “I know you better than that, EllRay Jakes. And something is troubling you. Is it your progress report?”

“Yeah, it's that,” I say, taking the easy way outâbecause she offered it to me.

Mom leans over to kiss my on my forehead, which is all wrinkled from fibbing. “Well, I wouldn't worry too much,” she tells me. “Time passes, doesn't it? I'll bet your work has already improved since Ms. Sanchez wrote that report.”

“But it's hard,” I say, telling the truth for the first time since she sat down.

“What's hard?” Mom asks.

“Paying attention in class,” I tell her. “And remembering all the rules. And sitting in my chair without wiggling. And not bothering my neighbor, even when she wants to be bothered. And not getting mad on the playground. It's hard just being

me

, Mom.”

me

, Mom.”

“Oh, EllRay, I know it is,” she says, scooping me into a hug. “But like I said before, being you is also a wonderful thing, honey bun.”

“Not so far it isn't,” I try to say, but my mouth is smooshed against her sweater and she probably doesn't even hear me.

Mom kisses me on my forehead again and pulls the covers up to my chin. “Well, nighty-night,” she says, as if every problem in every world, not just mine, has now been solved. “Close your eyes and go to sleep,” she tells me. “Because tomorrow's going to be a beautiful day, EllRay.”

Today has been a nervous Tuesday for me, I think, lying in the dark, especially because of what happened at lunch. But Mom has made it better, somehow. And I did make it through the afternoon without getting twisted, pounded, or whomped again.

So that's been one whole day without getting into trouble.

Maybe Mom is right. Maybe I can do it!

8

MS. SANCHEZ SAYS

“Quiet, ladies and gentlemen,” Ms. Sanchez says on

WEDNESDAY

morning from the front of the class, and she taps her solid-gold pen on her desk.

WEDNESDAY

morning from the front of the class, and she taps her solid-gold pen on her desk.

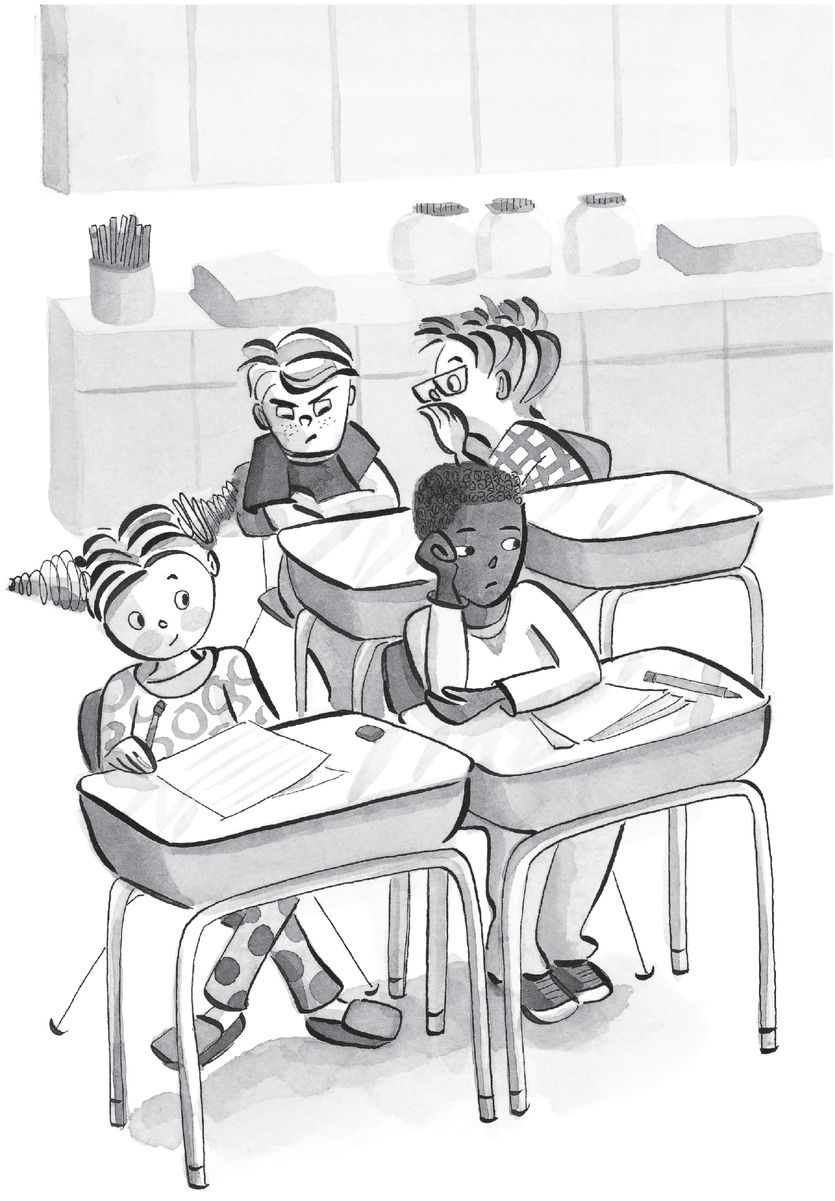

We all try to look as if we are paying attention, even though half of the class feels like falling asleep because the room is so hot, and the other halfâthe half with me in itâwants to run outside and play.

It is a beautiful day, just the way Mom said it would be.

“Pay attention, please,” Ms. Sanchez says, tapping her pen again. “I have an announcement. We're going to do a science experiment. It's Mudshake Day!”

“But I thought we only had to do science on Tuesdays,” Heather Patton says in a really loud whisper, because you're not supposed to talk out loud in class without raising your hand first.

Heather sits behind me in class, and ever since her teenage sister told her she was going to have to cut up a dead frog in science class when she is a teenager, she has hated the entire subject.

Heather doesn't even like frogs that are

alive

, much less dead.

alive

, much less dead.

I am not exactly looking forward to cuttin up a dead frog, by th way, but it might be interestingâ

if

the frog didn't get run over, and

if

it died of old age after leading a long and happy life. For a frog.

if

the frog didn't get run over, and

if

it died of old age after leading a long and happy life. For a frog.

“From now on, Heather,” Ms. Sanchez says with an ice cube in her voice, “please raise your hand if you have something to say.”

“Sorry,” Heather mumbles.

“With this experiment,” Ms. Sanchez says, sneaking a look at her notes, “we will continue our exploration of soil and its components.”

Okay. “Components” means “parts,” I happen to know, only Ms. Sanchez can't just say “parts,” for some reason. Probably because it's too simple a word, and we wouldn't get smart if she always said things the simplest way.

So Ms. Sanchez has to say “soil” when she really means “dirt,” for example.

Next to me, Annie Pat Masterson aims a smile at Emma McGraw, because they both love science, even when it's just about dirt.

“Here is what your ideal garden soil is made up of,” Ms. Sanchez says, and she writes something on the board:

1. 40% SAND

2. 40% SILT

3. 20% CLAY

“Now, who can tell me what this means?” she asks.

Cynthia raises her hand and starts talking before Ms. Sanchez even calls on her, which is typical of Cynthia. “âIdeal' means âbest,'” she says in a very loud voice, and she smiles, using all her teeth, and looks around like she is waiting for us to cheer.

Ms. Sanchez sighs. “That is correct, Cynthia.” she says. “But I was really talking about what the numbers on the board mean.”

“Well,

I

didn't know that,” Cynthia says, folding her arms across her chest and frowning, which is never a good sign with her.

I

didn't know that,” Cynthia says, folding her arms across her chest and frowning, which is never a good sign with her.

Cynthia is a girl who knows how to hold a grudge.

The whole class sits in silence for a minute, hoping someone will raise theirâherâhand.

In other words, we are counting on Kry Rodriguez to save us.

Kry's real name is Krysten, and she is pretty, with long black hair, and she moved to Oak Glen just before Thanksgiving, and she is very good at math. She slowly raises her hand like there is a red balloon tied to her wrist.

“Yes, Kry?” Ms. Sanchez says, smiling in relief.

Kry clears her throat. “I think the numbers mean that

almost

half of the soil is sand,” she says, “and

almost

half is silt, and half of almost-half is clay. Which adds up to one hundred percent.”

almost

half of the soil is sand,” she says, “and

almost

half is silt, and half of almost-half is clay. Which adds up to one hundred percent.”

“Big deal,” Cynthia coughs-says into her hand.

Heather laughs to back her up. “Whatever silt is,” she mutters.

“And what is silt?” Ms. Sanchez asks in her coldest voice. “Heather? Perhaps you can enlighten us.”

Other books

When a Man Loves a Weapon by Toni McGee Causey

Ridiculous by Carter, D.L.

400 Boys and 50 More by Marc Laidlaw

Sam (BBW Bear Shifter Wedding Romance) (Grizzly Groomsmen Book 2) by Becca Fanning

Ancient Images by Ramsey Campbell

Meet The Baron by John Creasey

Longarm and the Deadwood Shoot-out (9781101619209) by Evans, Tabor

A Twist of Fate by Joanna Rees

The Sons Of Cleito (The Abductions of Langley Garret Book 1) by Haines, Derek

Whispers of Fate: The Mistresses of Fate, Book Two by Deirdre Dore