Embers of War (107 page)

Authors: Fredrik Logevall

Tags: #History, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Political Science, #General, #Asia, #Southeast Asia

Movie-star handsome and a gifted orator, Dooley also embarked on a nationwide lecture tour, giving eighty-six talks in seventy-four cities. At least three-fourths of the talks were broadcast. Audience members reported being spellbound as he wove his tale; many broke down in tears as Dooley piled image upon wrenching image. “What do you do for children who have had chopsticks driven into their ears [by the Viet Minh]?” he would ask. “Or for old women whose collarbones have been shattered by rifle butts? Or for kids whose ears have been torn off with pincers? How do you treat a priest who has had nails driven into his skull to make a travesty of the Crown of Thorns?” In Dooley’s telling, the refugees were hapless victims, unable to think or act for themselves, utterly dependent on the heroic efforts of American doctors and sailors, while the Viet Minh were irredeemably evil, so devoid of conscience that Dooley referred to them simply as that “ghoulish thing.”

36

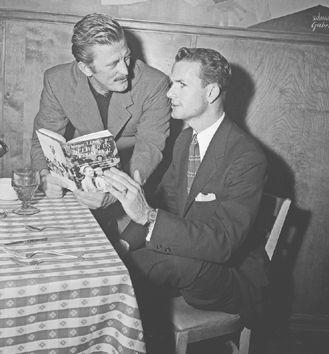

TOM DOOLEY AND KIRK DOUGLAS, THE ACTOR WHO WOULD PLAY HIM IN THE FILM VERSION OF DOOLEY’S BOOK,

DELIVER US

FROM EVIL

, CONVERSE IN A RESTAURANT IN APRIL 1956.

(photo credit 26.2)

Diem recognized what he had. He cabled a message to Dooley in the midst of the speaking tour to thank him for “the wonderful service you have rendered Vietnam.… [Y]ou have eloquently told the story … of hundreds of thousands of my countrymen seeking to assure the enjoyment of their God-given rights.” Other letters of praise came from President Eisenhower, Eleanor Roosevelt, Chief Justice Earl Warren, and Cardinal Spellman.

37

In due course,

Deliver Us from Evil

would be revealed for what it was: a wholly unsubstantiated account of the Passage to Freedom, studded with misleading claims and outright falsehoods. A group of U.S. officials who served in the Hanoi-Haiphong area during Dooley’s time there reported already in 1956 that his account was “not the truth” and that his accounts of Communist misdeeds were “nonfactual and exaggerated.” Their report, however, was kept secret. Lederer himself acknowledged in 1991 that the atrocities Dooley described “never took place.” Even more damning, one of the corpsmen who had served under Dooley’s command in Haiphong said years later that he never witnessed any of the barbaric spectacles detailed in the book.

38

At the time, however, in the mid-1950s, many Americans were ready to believe. To them, Dooley’s appalling account only confirmed what so many others in the culture were already saying: that Communists, in evangelist Billy Graham’s words, were “inspired, directed, and motivated by the devil himself, who has declared war on Almighty God.” That Dooley knew little about Vietnam or geopolitics—in his book and lectures, he got even elementary facts wrong—did not matter much, for his legions of adoring fans knew even less. By the millions, they bought what he was selling, literally and figuratively. Others would plead Ngo Dinh Diem’s cause in the mid- and late 1950s, but no one touched so many Americans, in such an emotional way, as the doctor from St. Louis.

VI

JULY 1956 CAME AND WENT. ACCORDING TO THE FINAL DECLARATION

at Geneva, the elections for the reunification of Vietnam, to be supervised by the ICC, were to be held in this month, but no voting took place, and July ended without incident in Vietnam and without much international comment. American planners breathed a sigh of relief; they had successfully bypassed an election they were certain their guy would lose. In the months thereafter, as U.S. aid dollars, technical know-how, and products poured into South Vietnam, some Washington officials spoke hopefully about a “Diem miracle,” about the RVN being a “showcase” for America’s foreign aid program. Saigon store shelves were well stocked with consumer goods, and food supplies were abundant. More than a thousand Americans were now in South Vietnam, assisting Diem in virtually all areas of civil and military administration, and the U.S. mission in Saigon was the largest in the world. American economic and security assistance totaled about $300 million per year starting in 1956—a manageable sum for taxpayers, even if it made Diem’s small state the fifth-largest recipient of American foreign aid.

The vast bulk of American assistance to South Vietnam was military. This accorded with Diem’s own preferences, and with John Foster Dulles’s view, expressed already in the summer of 1954, that a strong and effective South Vietnamese army would be an essential prerequisite to achieving political stability. (The Pentagon, it will be recalled, had said the opposite in 1954: that evidence of political reform ought to be a condition for expanded military aid.) From 1956 to 1960, 78 percent of American assistance to South Vietnam went into Diem’s military budget, a figure that excluded security items such as police training and direct equipment transfers. Conversely, only 2 percent of American funds went into programs such as health, housing, and community development.

39

Under Lieutenant General Samuel T. Williams, the Military Assistance and Advisory Group (MAAG) undertook a crash program to build the new South Vietnamese Army (formally the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, or ARVN) into an effective fighting force. A native of Texas and a veteran of both world wars as well as Korea, Williams was a tough, no-nonsense commander with a leathery face and a stiff mustache, who bore the nickname “Hangin’ Sam” for imposing the death penalty on a rapist in his regiment in Korea. The name also suited his character, that of a strong disciplinarian prone to issuing fierce tongue-lashings toward underlings.

Williams arrived in Saigon in 1955 wholly ignorant of the social, political, and cultural complexities of Vietnam and not in any big rush to learn. He was, however, a keen student of guerrilla warfare, having paid close attention to irregular operations in Korea. To be successful, he reasoned, the guerrilla must win the backing of a significant portion of the civilian population as well as access to supplies from friendly powers. Armed with this support, small and well-led guerrilla units could successfully tie down much larger conventional forces arrayed against them. They could achieve and retain the allegiance of the population by emphasizing the purity of their motives: to defeat colonialism, to stamp out corruption, to end governmental repression, to implement reforms. To defeat these guerrillas, Williams continued, superior military power would not be enough; rather, government officials needed a combined approach, involving political, psychological, economic, and administrative as well as military elements. In a succinct summation of what would later be called the “counterinsurgency” doctrine, Williams declared: “The major political and psychological mission is to win the active and willing support of the people.” Absent that, and absent a concomitant effort to cut the guerrillas off from supplies provided by the sponsoring power, no lasting victory could be achieved.

40

There was wisdom and prescience in this line of analysis, yet Williams was curiously unwilling to act on his own prescription. He dismissed as “communist propaganda” all reports of corruption and nepotism in the ARVN, even when presented with strong evidence that some officers embezzled official funds, ran prostitution rings, trafficked in drugs, and extorted the very peasants whose support Williams supposedly considered it so vital to win.

41

He also decided—on the basis of his Korean experience—that the guerrilla threat in South Vietnam was not so dire after all. The real danger, rather, was a massive conventional invasion across the seventeenth parallel. The DRV would use guerrillas, to be sure, but only to draw defenders away from border areas. Once the defenders fell into the trap of vacating the border, the hammer blow would follow. “Communist guerrilla strategy is simple,” Williams said to Diem.

By using a small amount of arms and equipment and a few good military leaders, they force [their opponents] to utilize relatively large military forces in a campaign that is costly in money and men. In Korea in 1950, the South Koreans were using three divisions to fight less than 7,000 guerrillas in the Southeast. When the North Koreans attacked, the South Korean Army suffered from this diversion as their army was not strategically or tactically deployed to meet the North Korean attack.

42

Building from this analysis, Williams rejected the need for comprehensive political reform that might facilitate popular support for the government and instead urged Diem to build his conventional forces. Diem needed little convincing. He and Williams formed a strong bond, and the two men would have regular sessions that lasted several hours. Typically, Diem held forth. “Sometimes the general was able to get in some important points,” an American aide recalled, “but most of the time it was a case of General Williams making small talk while the president just plain rambled.” The two would sit with an interpreter at a small table, upon which a tea service and a tray of Vietnamese cigarettes were laid out. Diem would pick up one cigarette after another—the interpreter would light them—take a puff or two, and then move to another brand. The hard-pressed translator would attempt to take notes, translate, and keep his lighter at the ready.

43

Williams set to work. Limited by the Geneva Accords to a total of 342 U.S. military personnel, he used various subterfuges to get the number up to 692. Utilizing these men he then reorganized and trained the ARVN, while Washington supplied approximately $85 million per year in uniforms, weapons, trucks, tanks, and helicopters. The United States also paid the salaries of ARVN officers and enlisted men, underwrote the costs of training programs, and bankrolled the construction of military facilities.

Gradually, a new, leaner South Vietnamese military took shape, its numbers totaling 150,000 troops organized into mobile divisions. Problems, however, remained. The army suffered from an acute shortage of officers, and many of those in senior positions were of marginal quality, in part because of Diem’s habit of choosing loyal rather than competent people for key posts. Trained specialists such as engineers and artillerymen were also lacking, and there were persistent concerns about the level of logistical support for troops in the field. “In the event of organized full-scale guerrilla and subversive activity by ‘planted’ Viet Minh elements, control of relatively large undeveloped areas of Free Vietnam would likely pass to the Viet Minh,” the Joint Chiefs of Staff concluded in a sober assessment in 1956. If faced with a conventional attack across the seventeenth parallel, meanwhile, the ARVN could likely hold out a mere sixty days, the Chiefs said.

44

For that matter, would Diem’s forces show sufficient fighting spirit to really engage the enemy at all? Low morale, a chronic problem for the Vietnamese National Army units operating under the French, remained a worry even now, two years after the cessation of hostilities. Few U.S. advisers were proficient in French, and almost none of them had even a basic command of Vietnamese. Nor were there nearly enough South Vietnamese interpreters and translators. The linguistic barriers were immense, especially as there were no expressions in Vietnamese for most American military terms and phrases. Misunderstandings were common, and mutual frustrations festered. Even more alarming to American analysts, many Vietnamese troops questioned why the United States—another big, white Western power—seemed so eager to help them and direct them. “Probably the greatest single problem encountered by the MAAG,” one of its officers wrote at the time, “is the continual task of assuring the Vietnamese that the United States is not a colonial power—an assurance that must be renewed on an individual basis by each new adviser.”

45

With time, of course, these complications could be worked out, and the South Vietnamese Army could be a professional and dedicated and well-trained force built on U.S. lines, capable of countering any threat to Diem’s rule. Or so MAAG officials told themselves. To Washington, they generally painted an optimistic picture, noting that the military training mission was proceeding apace and that the possibility of renewed fighting on a significant scale was remote. For Eisenhower and Dulles, however, it was welcome news, especially as other foreign policy issues rose to the fore. In the fall of 1956, the Middle East exploded in the Suez Crisis and the second Arab-Israeli war, resulting in major tensions between Washington and its British and French allies. Simultaneously, Nikita Khrushchev, who the previous year had cemented his control over the post-Stalin Kremlin leadership, sent Red Army units to crack down ruthlessly on anti-Soviet rebels in Hungary. Eisenhower opted for a policy of restraint in Hungary, but the twin crises, together with the prospect of rising tensions in Africa, made him more than willing to pay the price for continued calm in Vietnam.