Embers of War (19 page)

Authors: Fredrik Logevall

Tags: #History, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Political Science, #General, #Asia, #Southeast Asia

One is struck in retrospect by the bond that seemed to develop between the two men, and by the extent to which Ho Chi Minh and his colleagues devoted their energies during these crucial days to Patti. At each encounter, Viet Minh officials pressed Patti regarding U.S. plans for Indochina. The list of tasks they faced as the leaders of a new government was as long as it was daunting—to build a legitimate army; to bring food to a populace still suffering from the effects of the famine; to neutralize competing Vietnamese nationalist groups—but none loomed as large as securing international help in thwarting French and perhaps Chinese designs on their country. By his own account Patti responded cautiously, promising merely to pass on messages to his higher-ups, and to refrain from revealing Ho’s whereabouts to either the French or the Chinese. But more than once he also referenced Franklin Roosevelt’s staunch commitment to Vietnamese self-determination, an assertion that surely raised Vietnamese hopes but oversimplified FDR’s thinking and in any event ignored the change under Truman.

21

Like Roosevelt, Patti could on occasion succumb to a patronizing and cryptoracist view of the Vietnamese, doubting in some (but not all) reports to Kunming that the “Annamites” had the requisite political maturity either to hold their own in negotiations with the French or to govern effectively. But too much should not be made of this attitude, for he nevertheless favored an American policy that had as its aim keeping France from reclaiming control. The Viet Minh’s dedication and fervor, as demonstrated throughout the summer and especially in the heady days of late August, impressed Patti enormously, as did the broad support the front seemed to enjoy from the population. On the evening of September 2, after witnessing the extraordinary events that day in Ba Dinh Square, Patti reported by radio to Kunming, “From what I have seen these people mean business and I am afraid the French will have to deal with them. For that matter we will all have to deal with them.” The French, he concluded in another dispatch, had little chance of reasserting lasting control. “Political situation critical … Viet Minh strong and belligerent and definitely anti-French. Suggest no more French be permitted to enter French Indo-China and especially not armed.”

22

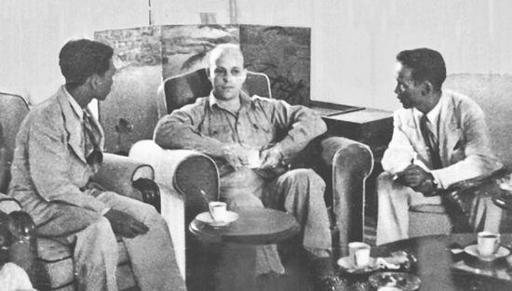

ARCHIMEDES PATTI, WHO REVELED IN THE ATTENTION, IS IN THE SEAT OF HONOR AS HE MEETS WITH VIET MINH OFFICIALS IN HANOI IN LATE AUGUST 1945. ON HIS RIGHT IS VO NGUYEN GIAP.

(photo credit 4.2)

France, however, was already on her way, and with tacit American blessing. At almost the same moment that Archimedes Patti’s airplane touched down in Hanoi, Charles de Gaulle, leader of the French Provisional Government, arrived in Washington, D.C., for a much-anticipated set of meetings with administration officials. No less than his nationalist rival in Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh, de Gaulle considered the United States the single most important player in the emerging Indochina drama, the main potential obstacle to his plan to once again tie the tricolor to the mast in Saigon and Hanoi. He had been encouraged, in this regard, by the U.S. positions at the San Francisco and Potsdam meetings, which he took to say that Truman would not stand in his way. But the Washington meetings nevertheless carried great importance for de Gaulle, and he made a studied effort to please. Upon landing in the American capital, he offered a glowing tribute to the United States in halting but tolerable English, and speaking in French at a state dinner at the White House that evening, he hailed America and France as

“les deux piliers de la civilisation.”

A whirlwind of activity followed, including visits to both the U.S. Naval and Military Academies, to FDR’s grave at Hyde Park, and to the vast new airport under construction in Idlewild, Queens (later JFK). In Manhattan, de Gaulle toured the city perched precariously on top of the backseat of a convertible, cheered by hundreds of thousands.

23

Behind the scenes, though, tensions simmered. There was no hiding the fact that, in the eyes of official America, France had suffered a dramatic loss in prestige. And though Truman did not share FDR’s deep personal dislike of de Gaulle, he questioned whether the general was the man for the job of pulling France together. De Gaulle took himself and his ideas far too seriously, the president told British officials in advance of the visit, and, “to use a saying that we have away back in Missouri,” was something of a “pinhead.” Truman said he intended to speak to the Frenchman “like a Dutch uncle” and make clear that Washington expected France to do its full part in her recovery. Whether France could ever recover fully was doubtful: To aides, the president said the French showed none of the “bulldog” tenacity exhibited by the British during the war. To the British ambassador, he said that whereas the rural people in Belgium were getting down to the work of recovery, their French counterparts were listless and content to wait for outside assistance to save them.

24

Yet there could be no question on providing that assistance, Truman believed. France might have fallen out of the ranks of great powers, but Washington needed a stable and friendly France in order to fully secure in peacetime the hard-fought victories of the battlefield. In Europe, this meant providing economic assistance of various kinds to the Paris government and working to smooth out Franco-American differences over the future of defeated Germany; outside Europe, it meant giving assurances that the French empire was, at least for the foreseeable future, secure.

25

On Indochina, administration officials sought to dispel any apprehensions on de Gaulle’s part regarding French sovereignty over the area. They did not object when, at a press conference on the twenty-fourth, he said that “the position of France in Indochina is very simple: France means to recover its sovereignty over Indochina.” And when de Gaulle remarked privately—and ambiguously—that Paris would be prepared to discuss eventual independence for the colonies, Truman replied that his administration would not oppose a return to French authority in Indo-china.

26

On August 30, Patti forwarded a message from Ho Chi Minh to President Truman, via American authorities in Kunming, that asked for the Viet Minh to be involved in any Allied discussion regarding Vietnam’s postwar status. Truman did not reply.

III

THERE WOULD BE MORE SUCH LETTERS IN THE WEEKS AND MONTHS

ahead; these too would go unanswered. Yet it is this first nonreply that lingers in the mind. August 1945 was the open moment, when so much hung in the balance, when the future course of the French imperial enterprise in Indochina was anyone’s guess. The energies of Truman and his top foreign policy aides may have been directed elsewhere that month—to the paramount tasks in postwar Europe, and to securing Japan’s formal surrender—but savvy French and Vietnamese leaders were not wrong to attach so much importance to American thinking. For at the occasion of Japan’s surrender, the United States had an extraordinary political power in Asia of a kind never seen before (or since). For tens of millions of Asians that summer, the very remoteness of America added to her allure, to her perceived omnipotence. In the words of journalist Harold Isaacs, who traveled in Vietnam and other parts of Asia for

Newsweek

in the fall of 1945 and wrote a book about the experience, the United States was “a shining temple of virtue of righteousness, where men were like gods amid unending poverty.” It was a country of awesome might, a country that could endure a string of defeats against a seemingly unstoppable foe, roar back to deliver a crushing and emphatic blow, and thereby stand astride all of Asia. Yet amazingly enough, America did not seek to use this power to engage in a colonial power grab; on the contrary, she sought to relinquish territorial control, as evidenced by her formal commitment to granting independence to the Philippines.

27

These were partial truths at best, Isaacs acknowledged, but tens of millions of Asians, many of them possessing scant knowledge of the outside world, believed them. For them, the United States could be “both altruistic and wise: altruistic enough to side with the cause of freedom for its own sake, wise enough to see that continued imperialism in the British, Dutch, French, and Japanese style would bring no peace anywhere.” For self-interested reasons, Washington leaders ought to be on the side of change in Asia. The recent war, after all, had exposed the crippling weaknesses of the old system. During Japan’s wave of attacks in the first half of 1942, the British, Dutch, and American colonies had collapsed one by one, like so many houses of cards. In Indochina, military action had proved unnecessary, as coercive diplomacy had been enough to beat down the French. In each of these places, the indigenous populations, with rare exceptions, had either welcomed the invaders, or stood by passively, or cleverly sought to exploit for their own gain the rupture between the colonialists. Everywhere Tokyo officials had proved unable to consolidate whatever initial support they received, thereby underscoring—in the minds of nationalists all over Asia—the degree to which colonial or colonial-type control would thenceforth be unsustainable.

28

Surely the United States would see all this, nationalists in the region told themselves and one another. Surely she would see that her postwar aims dovetailed perfectly with theirs. The United States, after all, was not like the other great powers, or at least it differed from them in key respects; whereas the British, the French, and the Dutch were wholly to be mistrusted, Americans could be believed, if not completely, then at least substantially. Ho Chi Minh, being more farsighted than most, had his suspicions on this score, as he revealed in his August letter to Charles Fenn, but even Ho held to what he thought was a well-founded hope that the Atlantic Charter’s principles would animate the postwar world. Archimedes Patti seemed to think they would; didn’t that mean something?

Not really, no. With his assurances to de Gaulle in Washington, Truman had indicated the course his administration would follow on Indochina, at least in the short term. Washington would not act to prevent a French return to Indochina. There were voices in the State Department who objected to this policy, who believed firmly that the United States had to stand for change, for a new order of things, a decolonization of the international system, but they had lost out to those in Washington who stood, in effect, for the old order of things, and who moreover had their eyes firmly fixed on Soviet moves in postwar Europe. French pleas would get their due attention and would be answered; Viet Minh pleas would not.

In historical terms, it was a monumental decision by Truman, and like so many that U.S. presidents would make in the decades to come, it had little to do with Vietnam herself—it was all about American priorities on the world stage. France had made her intentions clear, and the administration did not dare defy a European ally that it deemed crucial to world order, for the mere sake of honoring the principles of the Atlantic Charter.

But even on its own terms there are reasons to question the logic of the administration’s policy. Was it in fact logical, given the unquestioned importance of ensuring a strong France in Europe, to support her hard-line posture against a formidable nationalist movement in the far reaches of Southeast Asia? The looming conflict in Vietnam was sure to drain French strength away from Europe, to consume resources that all Paris officials knew were scarce to begin with, perhaps ultimately compelling Washington to in effect pay twice—once to bolster France in Europe, once to strengthen her in Indochina.

29

How things might have gone had Truman chosen differently is a tantalizing “What if?” question. There is scarce evidence that Ho Chi Minh would have allied himself with the United States in the emerging East-West divide, or that a reunified Vietnam under his leadership would have chosen a non-Communist path in the future. But neither should we assume that Ho necessarily would have aligned his nation closely with the Soviet Union in the Cold War; he might well have opted for an independent Communist course of the type Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito would follow. And certainly this much seems clear: A decision by the Truman administration to support Vietnamese independence in the late summer and fall of 1945 would have gone a long way toward averting the mass bloodshed and destruction that was to follow.

IV

ONE CAN IMAGINE THE SENSE OF RELIEF WITH WHICH INDOCHINA

planners in Paris greeted the news of Truman’s assurances during the Washington meetings. But these same officials knew that serious obstacles remained to the goal of achieving a swift assumption of control in the colony. Jean Sainteny, having arrived in Hanoi on board Patti’s plane, had found himself a virtual prisoner of Japanese forces and snubbed by Viet Minh officials. “Political situation in Hanoi worse than we could have foreseen,” Sainteny cabled Paris not long after arriving, acknowledging that Ho Chi Minh was the most popular figure in all the land. “Have found Hanoi solely decked out with [Viet Minh] flags.” In another missive he warned of a “concerted Allied maneuver aimed at eliminating the French from Indochina,” and in a third he spoke of a “total loss of face for France.”

30