Embers of War (34 page)

Authors: Fredrik Logevall

Tags: #History, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Political Science, #General, #Asia, #Southeast Asia

It was a bitter pill for Ho to swallow, not least because he knew the taste so well. He responded by redoubling his efforts to strengthen contacts with the French Communists and with Moscow. In September, the indefatigable Pham Ngoc Thach, fresh off his efforts with the Americans in Bangkok, traveled to Europe as Ho’s special envoy. He met with PCF leaders Jacques Duclos and Maurice Thorez, but he appears to have made no headway—Duclos impressed upon him the importance of Vietnam doing her utmost in the struggle for liberation, to which Thach replied that it was a shame the PCF had done so little to try to prevent the war. The Soviets too were more or less unresponsive. A measure of the importance they attached to Thach’s mission is that they chose not to bring him to the Kremlin to meet with senior officials; he got only an audience in Bern, with the Soviet ambassador to Switzerland. When Thach asked the ambassador if a later visit to Moscow might be possible, he received a noncommittal reply. No invitation ever came.

12

III

THE DANGER FOR HO IN THESE CONTINUING DIPLOMATIC FAILURES

was not merely that they perpetuated the Viet Minh’s international isolation, ensuring that the war would continue and that Giap’s forces would be fighting alone. They also risked undermining his personal as well as his government’s authority at home. If he could not convince most audiences abroad that the DRV was the sole and legitimate government of Vietnam, over time more and more domestic voices would have their own doubts on that score. Ho knew it, and his Vietnamese rivals knew it.

The French knew it too. More and more, as 1947 progressed, they pondered a tantalizing question: What if you could win the people’s allegiance away from the Viet Minh? Many Vietnamese, after all, northern as well as southern, did not support Ho’s revolution, were anti-Communist, and loathed Vo Nguyen Giap’s capacity for ruthlessness and repression. Could they be persuaded to coalesce around another Vietnamese leader who, if not exactly pro-French, would be less hostile to France’s aims? Senior strategists, led by Léon Pignon, thought so. Even as they rejected genuine negotiations with the Viet Minh and disavowed full independence for Vietnam, they cast about for such a figure, who would simultaneously draw support away from Ho Chi Minh and win favor with the Americans, and in the process win greater support for the war effort in the French Assembly, where many Socialists and all Communists were clamoring for an end to the fighting through negotiations with Ho. The move could also alter views elsewhere in Asia, where many national leaders condemned France for engaging in what they saw as naked colonial aggression.

13

One name stood out: Bao Dai, the portly, fleshy thirty-four-year-old former emperor who had abdicated during the August Revolution in 1945. If he could unite all anti-Communist nationalists behind him, the Viet Minh, reduced to a mere “faction,” would be forced to come to an agreement with France on French terms, or face defeat by the joint forces of the French and the Bao Dai government. If Ho refused to go along and kept fighting, the war would thenceforth not be a colonial struggle; it would be Vietnamese civil war, a war between Communism and anti-Communism, with France on the side of virtue, fighting for the Vietnamese and for the West against the Red Terror.

Thus came to the fore a rhetorical strategy from which the French would not deviate for the remainder of the war. It was disingenuous in the extreme, an ex post facto justification for a war initiated and fought on other grounds. Paris had no intention of granting the full independence that most every nationalist in Vietnam sought. But as a public rationale, the new approach was a kind of masterstroke, for it bought increased support for French aims in Vietnam and in the international community, most important in the United States. It was indeed tailor-made for American audiences. As the astute observer Philippe Devillers later said, through this “Bao Dai Solution,” Paris would use anti-Communism to neutralize America’s anticolonialism. An ostensibly nationalist regime would be the means by which the war against the Viet Minh would be redefined for Americans as part of the emerging struggle against Communism. And no longer would doves in Washington be able to claim that Ho Chi Minh alone represented legitimate Vietnamese nationalism.

14

Why Bao Dai? Because he enjoyed considerable influence among Vietnamese, and because the French thought he had the attributes they particularly valued: In their eyes, he was weak and malleable, concerned principally with indulging his passions for gambling, sport, and womanizing. It didn’t hurt that a number of other Vietnamese nationalists, including members of the Dai Viet and the VNQDD, expressed their support for Bao Dai against the Viet Minh, and that some leaders of the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao religious sects did the same. Ngo Dinh Diem, a prominent Catholic nationalist and later America’s “miracle man” in South Vietnam, asserted that Bao Dai could produce Vietnamese independence without the “Red Terror.”

15

Bao Dai’s biography allowed for these varying assessments. He had been crowned emperor upon the death of his father in 1925, at the age of twelve, whereupon he was sent to Paris for several years of schooling. He had studied music and literature, practiced tennis with French champion Henri Cochet, learned Ping-Pong and bridge, dressed in tweeds and flannels, and generally showed little inclination to return to his homeland. But return he did, formally becoming the thirteenth emperor of the Nguyen dynasty in 1932. Later he married the beautiful Mariette-Jeanne Nguyen Hui Tai Lan, the Catholic daughter of a wealthy Cochin Chinese merchant. They produced five children. To the surprise of some, Bao Dai quickly championed reforms in the judicial and educational systems and attempted to put an end to the more outdated trappings of Vietnamese royalty. He ended, for example, the ancient custom (

lay

) whereby mandarins would prostrate themselves before him with their foreheads touching the ground; thenceforth, a bow would be sufficient.

16

But the French swiftly made clear who held the real power, and the young sovereign gave more and more attention to his leisure activities. He devoted weeks at a time to hunting expeditions in the jungle highlands, reportedly bagging single-handedly a sizable percentage of Vietnam’s tigers. (He preferred to track the tigers into their dens, with a lamp attached to his head and a rifle at his side. One time, legend had it, he killed one with his bare hands.) Upon his abdication in August 1945, he became a “supreme counselor” to Ho Chi Minh, but by March 1946 he had disassociated himself from the Viet Minh and relocated to Hong Kong. A steady stream of messengers and old collaborators of the French now arrived in the British colony to urge Bao Dai to head a French-sponsored anti–Viet Minh government. Mus stopped by after his encounter with Ho, and Bollaert himself came in June. Bao Dai reacted cautiously and said he would demand of France as much as Ho demanded: the dissolution of the Cochin China government, the reunification of Vietnam under one government, and full independence.

BAO DAI AS A YOUNG BOY IN PARIS, WHERE THE FRENCH SENT HIM TO BE EDUCATED.

(photo credit 8.1)

The ex-emperor’s firmness surprised Frenchmen who looked upon him as nothing more than an indolent playboy. Lazy he was, and a pleasure seeker of the first order, but he was also an intelligent man whose bland, expressionless face hid a keen political sense, a quick study who perceived immediately that Paris officials sought to use him as a means to preserve colonial control. In July 1947, he announced that he was neither for nor against Ho Chi Minh’s DRV but above partisan squabbles, and he vowed that he would not return home unless his people wanted him. At the same time, a new National Union Front, composed of various anti–Viet Minh nationalist groups, urged all political, religious, and social groups to unite under Bao Dai. It exhorted the ex-emperor to lead the struggle for Vietnamese independence and unity and to fight the Communist menace.

17

In the months that followed, Bao Dai softened his stance and moved gradually closer to the French. Bollaert, admonished during meetings in Paris not to enter negotiations with Ho, gave a major speech at Ha Dong near Hanoi in September in which he offered not independence for Vietnam but a qualified form of “liberty” within the French Union. The Vietnamese could run their own internal affairs and decide “for themselves” whether Cochin China should join the Republic of Vietnam, but France would maintain control of military, diplomatic, and economic relations. There was no room for negotiation on these points, the high commissioner added; the offer “must be rejected or accepted as a whole.”

18

The Viet Minh dismissed the offer immediately, and various non-Communist nationalists denounced the speech for failing utterly to provide a rallying point for the anti–Viet Minh cause.

19

But Bao Dai—whose self-confidence always sagged at moments of crisis—indicated a willingness to deal with the French on this basis. It was a first step on the slippery road to surrender.

IV

IN RETROSPECT, WITH KNOWLEDGE OF WHAT WAS TO COME, FRANCE’S

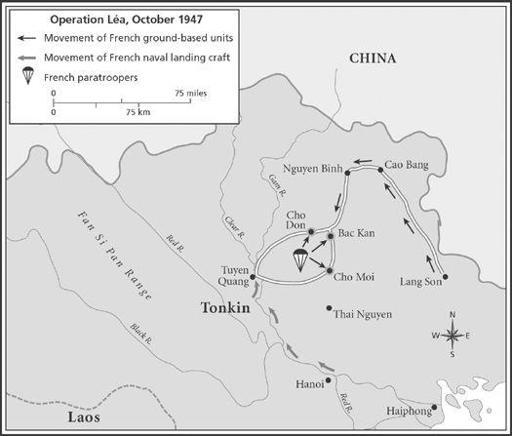

unyielding diplomatic posture in 1947 seems difficult to comprehend. But in the context of the time, it was hardly so strange. Ho Chi Minh, after all, was having minimal success winning broad international support for his cause, and French arms had scored numerous victories early in the year, before the arrival of the monsoon. Throughout the summer, many top officials continued to believe that a military solution was at hand—once General Valluy launched his fall offensive, they proclaimed, he would finish off the Viet Minh once and for all. The general did all he could to stoke this belief, and he received firm backing from War Minister Coste-Floret and Foreign Minister Bidault. On October 7, after months of careful planning and preparation, Valluy launched Operation Léa, a large-scale attack involving seventeen battalions and all the heavy equipment and modern arms the French possessed. (Almost certainly it was the largest military action in French colonial history to that point.) The principal aim was to capture the Viet Minh leadership at its headquarters in the Viet Bac and in the process destroy a sizable chunk of the Viet Minh army. In addition, Valluy hoped to isolate the Viet Minh and cut off their trading routes to southern China. In a single stroke, the war could be won, the French commander told superiors in Paris.

Immediately there were problems. Valluy’s plan called for a concentric attack involving airborne, amphibious, and overland columns. But the key initial phase, involving the dropping of paratroops near the Viet Minh headquarters at Bac Kan, foundered on the inability to get the troops in place quickly enough. It took three trips and many hours to get a mere 950 parachutists to the target area, forfeiting the advantages of surprise. Even then Viet Minh leaders were initially caught flat-footed and suffered heavy casualties: Though the DRV intelligence network had gotten wind of the operation two days earlier, a communication snafu meant that the information reached Bac Kan just as the French were launching the attack. Ho and Giap managed to get away, but with only minutes to spare. They were forced to leave behind arms and munitions caches as well as stacks of secret documents. One senior DRV official, the well-known scholar Nguyen Van To, was killed by paratroopers as he tried to escape.

20

Within a day, Giap had rallied the Viet Minh troops, and they battled the airborne troops on even terms. Meanwhile, the French northern pincer—ten battalions moving by road from Lang Son to Cao Bang and from there west to Nguyen Binh and south to Bac Kan, for a total of 140 miles—bogged down on account of ambushes, blown bridges, and piano-key ditches on the roads. Not until October 13 did the task force reach the vicinity of Bac Kan, and there the Viet Minh put up fierce resistance. Only on the sixteenth did the mechanized Moroccan Colonial Infantry Regiment break through to relieve the battered and encircled paratroopers. As for the southern pincer, consisting of four battalions moving by naval landing craft up the Clear and Gam rivers, it never reached the battle zone at all; on the nineteenth, its units, having been forced by sandbars and other obstructions to move to a land route, stumbled onto the northern task force moving south. On November 8, one month after it began, Operation Léa was called off.

21