Embers of War (44 page)

Authors: Fredrik Logevall

Tags: #History, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Political Science, #General, #Asia, #Southeast Asia

But there was also a dark side. Egocentric to the point of megalomania, de Lattre was prone to moodiness and to volcanic expressions of anger toward underlings. Meticulous in his personal appearance—he wore uniforms tailored by Lanvin, the stylish Paris couturier—he demanded that subordinates be likewise, and he bristled when on inspections his hosts failed to welcome him with the ceremonial he considered his due (hence a second nickname:

Le Roi Jean

, or King Jean). Always he was notoriously touchy about honor—both his own and his country’s. On one occasion, during a dinner for Allied commanders, de Lattre refused to touch his food and wine because Marshal Zhukov of the Red Army neglected to mention France in a toast praising Allied armies. Informed of his mistake, Zhukov offered a separate toast to France. A mollified de Lattre began to eat and drink.

6

At the conclusion of the war, General de Gaulle sent de Lattre to Berlin to participate in the Armistice ceremony, even though France hadn’t been invited. De Lattre signed as a witness and exulted: “Victory has arrived … radiant victory of springtime, which gives back to our France her youth, her strength and her hope.” This was not mere rhetoric. De Lattre believed in his country, believed in the empire, and in the postwar years did everything he could to restore France to what he considered her rightful place among the leading powers. Beginning in late 1945, he served as inspector general and chief of staff of the French Army and then as commander of Western Union (the precursor to NATO) ground forces—in effect, Western Europe’s top general.

His acceptance in late 1950 of the Indochina posting surprised some who saw it as a step down in professional terms, but for de Lattre there could be no question of declining. A gambler by nature, he had always trained his troops to embrace the need to take risks; now he had to live up to his teaching. More important, his country was at war, and the war was going badly, with his only son in the heart of the action. An outright defeat seemed all too possible. In this hour of maximum need, he had to answer the call. “I have nothing to gain and doubtless much to lose,” de Lattre replied when Prime Minister René Pleven asked him to take up the post. “All the more reason for accepting, and, as a good soldier, I shall do so without hesitation.”

7

De Lattre saw as his foremost aim keeping Indochina firmly within the French Union, but his initial utterances emphasized the menace posed by the forces of international Communism. He told the American journalist Robert Shaplen that France was in Vietnam “to save it from Peking and Moscow.” Paris might have acted out of colonialist motives in the past, but no more. “We have abandoned all colonial positions completely,” he assured a skeptical Shaplen. “The work we are doing is for the salvation of the Vietnamese people”—and the security of the Western world. The Vietnam struggle, he insisted at every opportunity, was another front in the war that the West was waging in Korea. The stakes were huge: “Tonkin is the keystone of the defense of Southeast Asia. If Tonkin falls, Siam falls with Burma, and Malaya is dangerously compromised. Without Tonkin the rest of Indochina is soon lost.”

8

Did de Lattre really believe it was so simple? It’s hard to be sure. His hatred of Communism knew no bounds, and he was convinced that his actions in Indochina ultimately mattered as much to the West’s defense as did MacArthur’s in Korea. But he also knew that the imagery of countries falling one by one, like bowling pins—or, as it were, dominoes—resonated in the halls of power in Washington, among both civilians and military men. And on this point de Lattre needed no schooling: The success or failure of the daunting task that confronted him, he knew, depended in large measure on the attitudes and policies of the Truman White House.

II

HE SET OUT FROM ORLY AIRPORT AT MIDNIGHT ON DECEMBER 13

. Some two thousand old comrades of the First French Army turned out to see him off, their banners fluttering in the nighttime breeze. It was a moving moment for de Lattre, proof, he said, that

les gars

(the boys, as he called his men) still trusted him, that the spirit of the First Army still lived. Five days later his plane touched down in Saigon. It was December 19, four years to the day since the outbreak of major war.

“His plane came in and de Lattre stood at the top of a flight of stairs, on the platform, the gangplank, and he turned his profile this way,” Edmund Gullion, second in command at the American legation, recalled of the scene. “He had a magnificent profile (something like MacArthur), and watching him arrive, he seemed seven foot tall, stiff and straight and he took white gloves and pulled them carefully on his hands, like that—a very symbolic gesture, symbolizing in the honor of the corps [that] a gentleman aristocrat was in office. But the symbolism of pulling on the gloves was lost on no one.… He was coming down to clean up this mess.”

9

Immediately he made clear that spit and polish, flourish and ceremony, would be the order of the day. The Guard of Honor presented arms, and the band played “The Marseillaise.” To de Lattre, however, the guard appeared slovenly, and in front of bystanders he ripped into the colonel in charge, a terrifying treatment known in French slang as the “shampoo.” He then unleashed a torrent of abuse on the bandleader, on the grounds that one instrument was out of tune. To all assembled, there could be no doubt: King Jean had arrived.

10

Later that day the general addressed a gathering of French officers, telling them he couldn’t guarantee any easy victories or early improvement in the battlefield situation. What he could promise was firm command: “From now on, you will be led.” He promptly canceled the order for the evacuation of women and children from Hanoi—“As long as women and children are here, the men won’t dare let go”—and announced that his wife would soon join him from Paris. He vowed that Tonkin would be held, rejecting claims by some French officers that a concentration on southern Annam and Cochin China was unavoidable. These statements immediately bolstered morale among civilians and troops, as did his announcement that he would fly immediately to Tonkin. (At this departure too there was a ceremony, and again de Lattre went on a tirade: He ordered twenty-five days’ confinement for the pilot of his plane, for failing to put the new commander’s insignia on the fuselage. To a bearded copilot, de Lattre snapped: “You’ve got five minutes to shave yourself clean!”)

11

In Tonkin, there was no denying the gravity of the situation. French Union garrisons on the northern and northeastern frontiers had been forced, due to the Viet Minh assaults in the Border Campaign, to withdraw to the Red River Delta, the possession of which de Lattre deemed essential to the defense of Indochina as a whole. Upon arriving in Hanoi, he reaffirmed that dependents would stay and again said he would not allow Tonkin to fall.

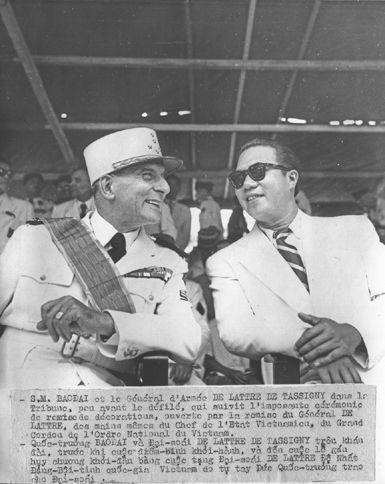

DE LATTRE AND BAO DAI DURING AN AWARDS CEREMONY IN EARLY 1951.

(photo credit 11.1)

In the days thereafter, he shuttled all over the delta in his small Morane spotter plane, showing scant regard for his own physical safety—more than once his entourage came under enemy fire—and a level of energy that left aides utterly exhausted. Everywhere he touched dormant chords of national pride and brought forth cheers from the assembled French troops; everywhere he ruthlessly weeded out the incompetent and the (by his standards) lackadaisical. His mantra at each stop: There will be no quitting Indochina until the Communists have been defeated.

But de Lattre knew that bucking up the fighting spirit of his soldiers, essential though it was, wouldn’t be enough. He consequently undertook a regrouping of French forces and reorganized the system of defense in Tonkin. Relying on the Armée d’Afrique tactics he had learned under Marshal Lyautey in Morocco in the 1920s, de Lattre emphasized the need for mobility, even in terrain that limited rapid movement to roads, with the accompanying dangers of ambush. Accordingly, he organized

groupes mobiles

(striking groups), each consisting essentially of a headquarters with sufficient command and communication facilities, to which could be assigned three or more infantry battalions and supporting troops. These

groupes mobiles

would move quickly to engage Viet Minh units and relieve besieged posts; when attacked, they would use the Armée d’Afrique tactic of simultaneous assault from at least two, and sometimes three or more, different encircling directions. The artillery, firing from the road deep into the jungle, would be dispersed throughout the length of a column and thus could not all be lost in a single ambush.

12

To enhance mobility and protect the delta, de Lattre ordered the construction of a series of self-contained and mutually supporting defense works, or blockhouses, all around the area. This chain of fortified concrete positions—built in groups of five or six, one or two miles apart, and designed to accommodate between three and ten soldiers—which became known as the “De Lattre Line,” had been recommended in the Revers Report of May 1949, but nothing had been done. Until now. De Lattre supervised much of the construction personally and drove the crews mercilessly; by the end of 1951, more than a thousand of the posts had been created, on a line that stretched in a rough semicircle from the sea near the Baie d’Along, along the northern edge of the delta to Vinh Yen, and then southeast to the sea again near Phat Diem, enclosing protectively both Hanoi and Haiphong. (See map on

this page

.) Supported by these positions, the

groupes mobiles

could set forth in search of enemy units, and also—in theory, at least—protect against rice smuggling as well as major Viet Minh assaults.

Two problems remained, however: finding enough bodies to man these many hundreds of strongpoints, and making sure the troops were adequately supplied. To meet the first objective, de Lattre sought and received reinforcements of North African units and Foreign Legionnaires. He knew, though, that Paris would never authorize sufficient numbers of troops for Indochina to do more than hold the line. The money wasn’t there.

13

He therefore accelerated what the French were now calling the

jaunissement

(literally “yellowing”), the building up of the still-embryonic Vietnamese National Army (VNA). At the time of de Lattre’s arrival, these comprised eleven battalions and nine gendarmerie units, and he swiftly ordered the creation of an additional twenty-five battalions, four armored squadrons, and eight artillery batteries. This Vietnamese force would perform the task, so the argument went, of pacifying and defending areas not under effective Viet Minh control, thereby freeing the Expeditionary Corps for offensive action. Many of the best officers and NCOs of the French Army, among them Bernard, volunteered to serve as the necessary initial cadres for these Vietnamese units.

14

For equipment, de Lattre turned to the United States. He took satisfaction from that fact that Washington’s aid had begun flowing more freely, and in particular he welcomed the dispatch of dozens of Bearcat fighters and B-26 bombers, as well as transportation equipment and bulldozers. American artillery shells were also arriving in much larger quantities, as were vital 105mm howitzers. But much more would be needed. From the U.S. liaison office in Indochina, de Lattre requested urgently needed materials. Among the items was an American weapon designed for jungle fighting: napalm. His predecessors had made scant use of this jellied petroleum that ignites on contact, but de Lattre determined at once that it could have enormous utility.

15

III

IN HIS JUNGLE HEADQUARTERS NEAR THAI NGUYEN, FIFTY MILES

north of Hanoi, General Vo Nguyen Giap greeted the news of de Lattre’s appointment with satisfaction, even delight. Always fascinated by military laurels and recognition, Giap viewed the selection of such an illustrious figure as a compliment to himself and to his troops, and he eagerly took up the challenge. “The French are sending against the People’s Army a foe worthy of its steel,” he declared. “We will defeat him on his own ground.”

16

Brimming with confidence following his victories in northern Tonkin, Giap now set his sights upon the Red River Delta and Hanoi. His Chinese advisers, flush with excitement about the success of the Border Campaign and of their human-wave attacks against the Americans in Korea, now urged Giap to use the same tactics against the French in Vietnam.

For some months, a debate had been raging in high Viet Minh councils about whether the time had come to shift to the third and final stage of Maoist people’s war, the general offensive. Did the success in the autumn offensive suggest that conditions were now ripe? Was a “preponderance of forces” in just one area sufficient, or did one need to have it all over the country? How vulnerable were the French in the delta, and would a Viet Minh victory there presage the crumbling of the entire colonial edifice? Senior officials went around and around on these questions; Giap was among those who argued that his forces could move to the third stage before they held absolute material superiority on the battlefield. Others disagreed, but Giap’s advocacy received a boost from the growing rice shortage in Viet Minh–held areas; unless revolutionary forces could expand their presence in the delta, he and others insisted, the food situation would become desperate. (Already the government had ordered people to drastically curtail their consumption of rice so that sufficient amounts would be available to the armed forces.) A fragile consensus emerged to launch the opening stages of what seemed likely to be a protracted and complex offensive. The first stage: a major assault on the delta from the northwest.

17