Embers of War (9 page)

Authors: Fredrik Logevall

Tags: #History, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Political Science, #General, #Asia, #Southeast Asia

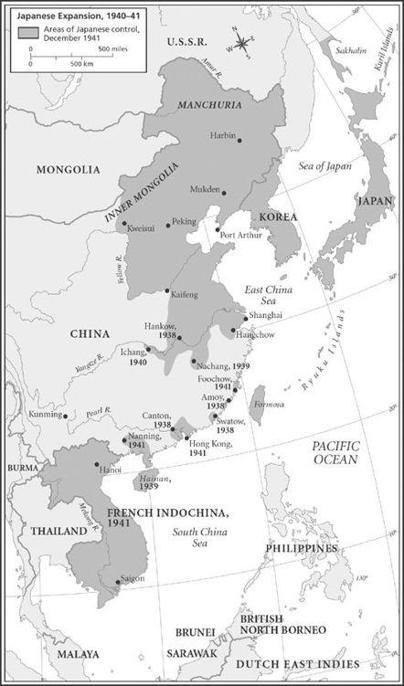

It was not to be. In 1941, Japanese attention turned southward again. In September 1940, Tokyo had officially joined the Axis by signing the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy. In the months thereafter, army minister and then prime minister Hideki Tojo and his colleagues plotted their next move. To facilitate good relations with Thailand, Tokyo officials consented to a Thai plan to attack Indochina in order to regain territory on the right bank of the Mekong River ceded to Laos and Cambodia at the turn of the century. A series of Franco-Thai skirmishes ensued, with no clear victor except in a naval battle that the French won handily. Yet even though Thailand got the worst of the encounter, Japan, eager to have Thai cooperation for a planned drive toward Singapore and Burma, forced upon France a settlement that granted Thailand many of her claims. Once again, the hollowness of independent French colonial rule over Indochina was exposed.

37

In April 1941, Japan signed a nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union, then watched with satisfaction as Hitler’s forces invaded Russia in June. The Japanese might have used this occasion of Soviet weakness to conquer parts of Siberia—a plan they actively considered—but instead they concentrated on expanding the empire to the south. On July 14, only ten months after signing its agreement with France, Tokyo presented Vichy with a new ultimatum that would allow the establishment of Japanese bases and troops in southern Indochina. Vichy consented, and on July 25 Japanese troops landed in Saigon to occupy strategic areas in the south, including the key port of Cam Ranh Bay and airfields at Da Nang and Bien Hoa. This gave the Japanese a forward vantage point from which to move quickly against Malaya, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies (today’s Indonesia), and the Philippines. There was jubilation in Tokyo, where nobody seemed to remember the cautionary words a few weeks before of Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka, who worried that such an operation would bring innumerable logistical difficulties and risk war with the United States. “A military operation in the Southern Seas,” Matsuoka had warned, “will court disaster for our country.”

38

V

AND INDEED, THE MIKADO’S MOVE INTO COCHIN CHINA LAUNCHED

a series of actions and reactions that put Japan and the United States on a collision course, culminating in the outbreak of war five months later. Events in Vietnam, so much a concern of a succession of postwar American presidents, and arguably the undoing of two of them, proved decisive here as well, in the last half of 1941, in making the United States a belligerent, and in joining the Asian and European conflicts into one

world

war.

Early on July 24, the White House received word that Japanese warships had appeared off Cam Ranh Bay, and that a dozen troop transports were on the way. American analysts were stunned, even though cables from the Paris embassy and MAGIC intercepts

39

—decoded Japanese communications—had told them for days to expect such a southward thrust. They grasped immediately the threat posed to the U.S. position in the Philippines and the British posture in Malaya and Singapore. That afternoon President Roosevelt summoned Japan’s special envoy, Admiral Kichisaburo Nomura, to the Oval Office and proposed a neutralization of Indochina. In return for the withdrawal of all Japanese forces, Washington would seek an international agreement to regard Indochina as a neutral country in which the existing French government would remain in control. The president must have known the proposal would find little favor in Tokyo, for he did not wait for a response before taking a much more forceful step: On the twenty-fifth, the administration froze all Japanese assets in the United States, imposed an embargo, and ended the export of petroleum to Japan.

Just what Roosevelt and his aides sought to achieve by this aggressive response has divided historians for more than half a century, but it seems most likely that the president himself did not intend to cut off all petroleum exports or mean for the freezing of assets to be permanent. He wanted to create uncertainty in Tokyo, not provoke a U.S.-Japanese war. Contrary to FDR’s intention, however, second-echelon officials in the State Department—among them Dean Acheson, later to be secretary of state under Harry Truman and an important player in our story—imposed a total embargo while the president was meeting with Winston Churchill at Placentia Bay, off the coast of Newfoundland. By the time Roosevelt returned to the capital on August 16, it was deemed too late to step back, for reasons political and diplomatic. The embargo received strong popular support, and polls showed that a majority of Americans now preferred to risk war rather than allow Japan to become more powerful. Furthermore, U.S. officials feared that the Japanese would see any modification as a sign of American weakness.

40

For Japan, so poor in natural resources, the implications were dire. The country consumed roughly twelve thousand tons of oil each day, 90 percent of it imported, and also imported most of her zinc, iron ore, bauxite, manganese, cotton, and wheat. She could not survive a year of a thorough embargo—unless she seized British and Dutch possessions in Asia. Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, a moderate among hard-liners, proposed a summit meeting with FDR and indicated a willingness to withdraw from Indochina as soon as the war with China was settled. Roosevelt was tempted by this offer, but his secretary of state, Cordell Hull, persuaded him to insist on Japanese abandonment of China as a precondition for such a meeting. The proposal collapsed, and Konoe was ousted as prime minister in mid-October. Tojo replaced him. Diplomatic maneuverings continued, and in November Tojo offered to move troops out of Indochina immediately, and out of China once general peace was restored, in return for a million tons of aviation gasoline. Hull rejected the offer and repeated the American insistence on Japanese withdrawal from China and abandonment of the Southeast Asian adventure. On December 7, Japan’s main carrier force, seeking to destroy the American fleet and thereby purchase time to complete its southward expansion, struck Pearl Harbor.

The news rocked world capitals. No one doubted that American involvement changed the equation, not merely in the Asian conflict but in the European war—this even before Japan’s Axis partner Germany declared war on the United States on December 11. For Charles de Gaulle, the end result was now assured. “Of course, there will be military operations, battles, conflicts, but the war is finished since the outcome is known from now on,” he remarked. “In this industrial war, nothing will be able to resist American power.”

41

Since his June 1940

appel

, de Gaulle had worked to establish the legitimacy of the Free French as authentic representatives of the nation in the eyes of the Allies, on whom he depended for both economic and military support. The colonies that backed him played an essential part in this endeavor, because with their support de Gaulle could claim for the Free French a status analogous to the other governments-in-exile that were then active in London, even though both Britain and the United States maintained relations with Vichy and recognized it as the legitimate successor to the Third Republic. Although the effort to rally colonial support had met with only limited success—in late 1941, Vichy still controlled the most important areas of the empire—de Gaulle hoped Pearl Harbor would change the equation. On December 8, he proclaimed common cause with Washington and declared war on Japan.

CHAPTER 2

THE ANTI-IMPERIALIST

D

E GAULLE’S MOMENT OF HOPE DID NOT LAST LONG. PEARL HARBOR

and the American entry into the war, it soon became clear, had failed to improve his organization’s standing in Washington. In the eyes of President Franklin Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull, the Free French continued to be an illegitimate and potentially dangerous group, with which limited agreements might be negotiated on matters of pressing concern but which was in no way representative. It certainly did not have to be consulted when French interests were at stake. Both men believed that Franco-German disputes lay at the root of much of Europe’s inability to maintain the peace. Both doubted that France could be a stabilizing force in world affairs after the war, given what they saw as her weak political system and the failure of her armed forces to put up more of a fight against the Wehrmacht. France was a fading power, Roosevelt believed. Her people, he told aides, would have to undergo a fundamental transformation in order to have a workable society.

1

Roosevelt had not yet met de Gaulle, but he knew enough to dislike him. Basic personality differences played a role. In social interaction, de Gaulle was as austere and pompous as FDR was relaxed and jovial. For months, Roosevelt had heard Hull and other advisers rail against the general’s egotism and haughty style, his serene confidence that he represented the destiny of the French people. Roosevelt, with his preference for the complicated, the ambiguous, and the devious, would get irritated just listening to these aides. In Kenneth S. Davis’s perceptive formulation, the president was often contemptuous of “men who pursued their objectives in uncompromisingly straight lines, men who disdainfully eschewed the tactics of … cajolery and concealment and misdirection, which were for Roosevelt part and parcel of the art, or the game, of elective politics.”

2

That the two men sought to convey fundamentally different images exacerbated the problem. Successful American presidents project a populist image. They do not place themselves above their compatriots but strive whenever possible to show qualities typical of “average” Americans. If they have an intellectual bent, they do their best to hide it. To be likable, smiling, and unpretentious is all-important; to express the values of middle America an essential prerequisite for greatness. In France, great leaders historically do exactly the opposite: They stand above the masses, remote figures embodying France’s

gloire

and

grandeur

. They don’t try to be folksy or common in speech. No one cultivated this image more assiduously than de Gaulle. The general was not shy about invoking

Notre Dame de France

—Our Lady of France—or about identifying himself with national heroes such as Jeanne d’Arc and Clemenceau. Roosevelt, though reasonably familiar with the French language and culture, did not comprehend this French mythmaking, while de Gaulle, in his general ignorance of American ways, viewed FDR’s geniality as a guise for hypocrisy and artifice.

3

Relations between de Gaulle and Roosevelt suffered a major blow on Christmas Eve 1941, when Free French troops, acting on de Gaulle’s orders, occupied St. Pierre and Miquelon, two tiny Vichy-controlled islands off Newfoundland with a population of five thousand. Roosevelt opposed anything liable to alienate Vichy, and Cordell Hull, already convinced that de Gaulle was a fascist and an enemy of the United States, condemned this “arbitrary action” by the “so-called Free French.” Residents of the islands, however, held a plebiscite resulting in a near-unanimous vote for affiliation with de Gaulle’s organization. And the American media, led by

The New York Times

, lauded the general’s initiative and attacked Hull. The St. Pierre–Miquelon affair infuriated and embarrassed Roosevelt, who emerged from it with the strong suspicion that the leader of Free France was not himself committed to human freedom and would, if given the chance, establish a dictatorship in postwar France.

4

II

THAT DE GAULLE FULLY SHARED VICHY’S DESIRE TO PRESERVE THE

French Empire only enhanced Roosevelt’s disdain.

5

By the time of Pearl Harbor, he had become a committed anticolonialist. European colonialism had helped bring on both the First World War and the current one, he was convinced, and the continued existence of empires would in all likelihood result in future conflagrations. Western sway over much of Asia and Africa was no less threatening to world stability than German expansionism, he went so far as to say. Therefore all colonies should be given their independence. The president’s son Elliott records FDR as saying, some months after U.S. entry into the war: “Don’t think for a moment, Elliott, that Americans would be dying in the Pacific tonight, if it hadn’t been for the shortsighted greed of the French and the British and the Dutch. Shall we allow them to do it all, all over again [after the war]?” Although the reliability of Elliott’s direct quotation may be questioned, there is little doubt he captured his father’s basic conviction. Earlier, in March 1941, FDR had told the White House Correspondents’ Association: “There has never been, there isn’t now, and there never will be, any race of people on earth fit to serve as masters over their fellow men.… We believe that any nationality, no matter how small, has the inherent right to its own nationhood.”

6