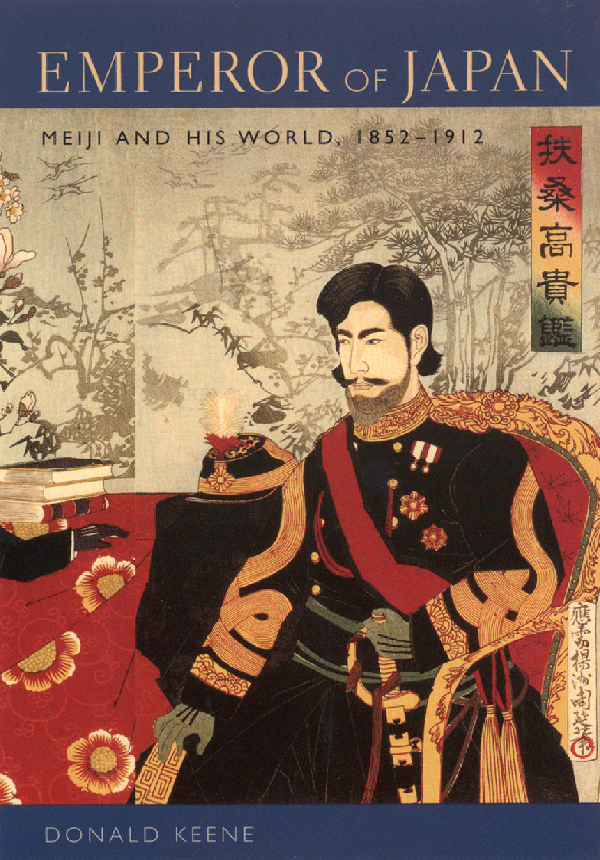

Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852’1912

Read Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852’1912 Online

Authors: Donald Keene

Tags: #History/Asia/General

Emperor of Japan

M

EIJI AND

H

IS

W

ORLD

, 1852 – 1912

Donald Keene

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation

for assistance given by the Japan Foundation

toward the cost of publishing this book.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

Copyright © 2002 Donald Keene

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-51811-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in Publication Data

Keene, Donald.

Emperor of Japan : Meiji and His world, 1852–1912 / Donald Keene.

p. cm.

ISBN

0-231-12340

-X (cloth : alk. paper)

1

. Meiji, Emperor of Japan 1852–1912. 2. Japan—History—Meiji period,

1868–1912. 3. Emperors—Japan—Biography. I. Title.

DS882.7.K44 2002

952.03′1′092—dc21 2001028826

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at

[email protected]

.

To the Memory of Nagai Michio (1923–2000)

Friend and Teacher

CONTENTS

At the northern end of the Gosho, the grounds surrounding the old imperial palace in Ky

ō

to, just inside the wall marking the perimeter, there stands a small house. In the early years of the Meiji era, when American missionaries were first allowed to reside in the old capital, they used the house for a time to store their furniture and other belongings while they searched for a domicile. Today it attracts little attention, even though it is one of the few houses belonging to the nobility to have survived not only the conflagration that swept through the Gosho in the middle of the nineteenth century but also the dilapidation and destruction following the move of the capital to T

ō

ky

ō

in 1868.

Outside the fence that protects the house and garden from intruders is a small wooden marker inscribed Sachi no i, the Well of Good Fortune, and inside, barely visible over the top of the fence, is a more considerable stone monument. These two reminders of the past are all that alert the visitor to the fact that the building possesses greater significance than as an example—a very unimpressive example—of nineteenth-century traditional Japanese architecture. In fact, Emperor Meiji

1

was born in this house in 1852, and (according to unreliable tradition) he was first washed in water from the Well of Good Fortune.

2

Meiji was born in this inconspicuous building rather than in the imperial palace itself because his mother, Nakayama Yoshiko, had been obliged by custom to leave her quarters in the palace when it became evident that she would soon give birth. It was traditionally believed that a birth polluted the building where it occurred, and for this reason children of the emperor were normally born near their mother’s house, often in a separate building that was likely to be destroyed when no longer needed. Ironically, this little house has lasted longer than the elaborate residences of the nobility that once surrounded it, vying proud roof against roof.

In preparation for the imperial birth, Yoshiko’s father, the acting major counselor Nakayama Tadayasu, had erected this “parturition hut” next to his own, more substantial dwelling. He at first attempted to persuade his neighbors to let him use land they were not actually occupying, but even though the child who was to be born might well become the emperor, he was refused by all and, in the end, had to build on his already crowded property. Like many other nobles at the time, Tadayasu was too poor to pay the costs of even so modest a structure—two small rooms with a bath and toilet attached—and had to borrow most of the money needed for the construction.

3

Although the house is itself unimpressive, it is strange all the same that the birthplace of a deified emperor, whose shrine in T

ō

ky

ō

, the Meiji jing

ū

, attracts millions each New Year and many thousands of worshipers even on quite ordinary days, should be the object of so little interest and treated so casually. Only recently has the little house, badly neglected over the years, been given new tiles for its roof. This unmitigatedly utilitarian dwelling, with bare boards on the floor and not a trace of ornamentation anywhere, hardly suggests that this is where a prince was born who became Japan’s most celebrated emperor.

The indifference displayed toward Meiji’s birthplace characterizes also, in a curious way, general knowledge of the man: even Japanese who believe that Meiji was the greatest Japanese ruler of all time may have trouble recalling a single accomplishment that might account for so glorious a reputation. Meiji is associated, of course, with the “Meiji Restoration” of 1868, the beginning of Japan’s modern history, but he was only fifteen when it occurred and, at that age, was obviously incapable of making a significant contribution to the Restoration or to the momentous changes that immediately ensued. His name is associated also with victories in wars with China and Russia and with the securing of an alliance with England, although his role in these events was surely that of a benign presence, not that of a formulator of policy or military strategy. Yet it is also true that throughout his reign and even much later, he inspired men to perform extraordinary deeds of valor. There was no question in the minds of the men who effected the changes of the new regime that he was the guiding spirit.

The general lack of knowledge of the man is not the result of any large-scale suppression of evidence. There is ample documentation for almost every occurrence of Meiji’s life from his birth to his death. The official chronicle,

Meiji tenn

ō

ki

(Record of the Emperor Meiji), lists, on a virtually day-to-day basis, not only events in which he directly participated but relevant occurrences in the world around him. Many books and articles recalling Meiji’s daily life and personality were published after his death by people who knew him, but these books somehow fail to leave much impression. As the first emperor ever to meet a European, he figures also in the journals of foreign dignitaries who visited Japan. Their accounts, less inhibited than those by the comparatively few Japanese who were admitted to his presence, are of particular interest for their candid descriptions of his appearance from the time he first appeared before the public; but even they tell us little about the man.

In addition to the host of facts in the twelve closely printed, stout volumes of the official record, there are innumerable legends and anecdotes about Meiji, notably the gossip concerning such subjects as his amours and the amount of liquor he consumed. There are even people who proudly claim to be illegitimate descendants, usually with only the flimsiest of evidence. Indeed, so much material is available that it might seem that the only requirement for a scholar who intended to write a well-rounded biography was patience; but Meiji’s biographers have rarely succeeded in the most essential task, creating a believable portrait of the man whose reign of forty-five years was characterized by the greatest changes in Japanese history.