Empire of Sin (11 page)

Authors: Gary Krist

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #True Crime, #Murder, #Serial Killers, #Social Science, #Sociology, #Urban

Story’s innovative new idea was

widely applauded by the city’s business reformers in particular; they hoped that isolating vice in this way would improve New Orleans’ reputation and thus make it easier to attract Northern capital investment. Even the conservative

Daily Picayune

lauded the proposal, looking forward to a time when the perpetrators of vice and immorality would operate only in “

obscure neighborhoods, where decent people will not constantly be offended by their open and shameless flaunting.” The city’s so-called moral reformers—the clergymen, bluestockings, and others who would rather have outlawed prostitution entirely—were naturally less pleased. But even they seemed willing at least to give the new proposal a chance.

The area designated as the so-called restricted district (though it soon would be known as Storyville, much to the alderman’s annoyance) was located behind the Vieux Carré, downriver of Canal Street. This was

a mixed-race working-class neighborhood that contained only one church—the Union Chapel, a Methodist Episcopal establishment with an exclusively African American congregation that lacked any political clout. A second, much smaller area uptown of Canal Street (eventually known as Black Storyville) was also designated, though unofficially, in order to forestall a wholesale exodus of black prostitutes already entrenched there. Known prostitutes in all other parts of town would be ordered to move to the restricted districts by a certain deadline; if they did not comply,

notices of eviction—signed by Mayor Flower himself—would be sent and acted upon if necessary.

On January 29, 1897, Alderman Story’s ordinance was passed by the city council (an amended version would be passed again in July). And so,

on the first day of 1898, Storyville would officially be born.

Long before that date, of course, brothel landlords and other vice entrepreneurs scrambled to establish beachheads within the confines of the new district. And one of the first among them was Tom Anderson. Always well connected to sources of insider information, he moved quickly to acquire

a choice property in Storyville-to-be. He bought the Fair Play Saloon, a large restaurant located on the corner of Basin Street and Customhouse, right at the point where most visitors would be entering the district, and made plans to renovate it into a showplace. Josie Arlington, too, acquired a lavish property on Basin Street, just a few doors down from Anderson’s. The vast commercial potential of operating within a legally tolerated vice district was not lost on either of the two entrepreneurs, and they were determined to take full advantage of the opportunity.

Anderson in particular saw the coming change as propitious. Until now, he’d had to operate his more questionable enterprises on the gray margins of the law, subject to the whim of any overzealous police captain or city politician eager to make a show of cracking down on vice and petty crime. Now Anderson would be able to operate with the explicit blessing of the authorities. To him, it seemed like an ideal arrangement. Maybe this new crop of reformers wasn’t so bad. With enemies like this, who needed friends?

And so Anderson began to lay his plans. He could set up shop in a bigger way in the new district. He could call in some political favors from his friends at the Choctaw Club—where the Ring political organization held court—and get himself elected to some position that might prove useful. And maybe he could even find some way of getting rid of his unwanted second spouse. For a man with an entrepreneurial streak and a flexible sense of propriety, the possibilities in this new scheme were virtually endless.

As for Alderman Story, Mayor Flower, and the other reformers, they too had good reason to expect that their segregated vice district would be a success, lending a semblance of order to a chaotic aspect of the city’s life that had resisted all previous attempts at regulation. What they did not anticipate, however, was quite how wildly successful their well-meaning social experiment would become.

BUT THERE WAS ANOTHER PHENOMENON BREWING in those areas soon to be set aside by the city fathers as enclaves of sin. At first, no one—certainly not those city fathers themselves—would recognize it as anything significant or worthy of notice. But for the one-quarter of New Orleanians designated in the census as “Negro,” the phenomenon would come to be very important indeed—a way of coping with the changes around them, a way of holding their own, of asserting their identity in a time of adversity.

The new sound was born sometime in the mid-1890s, in the working-class black clubs and honky-tonks near the

poor Uptown neighborhood soon to be known as Black Storyville. You could hear it in the venues on and around South Rampart Street—at Dago Tony’s, the Red Onion, Odd Fellows Hall—or farther afield in the “Negro dives” on the other side of Canal. For a time, the music was known only to those who flocked to such places, the so-called ratty people—“

the good-time, earthy people,” as one musician of the day defined them. But before too long, the new sound was also being heard in parks, on street corners, in dance halls, and in places well beyond the confines of the city’s destitute black neighborhoods. And that, naturally, was when the trouble started.

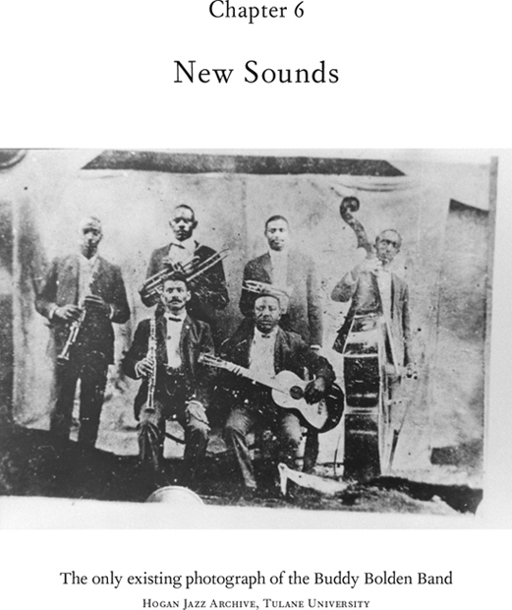

No one ever recorded the New Orleans musicians of the 1890s, so it’s difficult to say for sure that it was a young Uptown cornetist named Buddy Bolden who first played the music later known as jazz. Certainly many others—black, mixed-race, and even white—would eventually lay claim to the distinction. But many of his contemporary musicians believed that Bolden was the man who started it all, and to hear them tell the story, he was extraordinary: “

That boy could make women jump out the window,” one of his early listeners said. “He had a moan in his cornet that went all through you.” For many people in New Orleans, accustomed to the straighter, more schooled styles of music that preceded it, the Bolden sound was a revelation: “

I’d never heard anything like that before,” one convert would later say. “I’d played ‘legitimate’ stuff. But this, it was something that pulled me in. They got me up on the [band]stand and I played with them. After that I didn’t play legitimate so much.”

Charles Joseph “Buddy” Bolden, like so many of the jazzmen who would follow him, grew up poor and without much in the way of material prospects.

The grandson of slaves, he was born on September 6, 1877, in a small house on Howard Street in Uptown New Orleans. As neighborhoods go, it was

not a very healthy place to live, perched on the edge of a fetid and foul-smelling canal. By the time Buddy was six years old, he had lost his father, one sister, and his grandmother to various illnesses. Buddy and his sister Cora moved around with their mother, Alice, for the next few years, probably staying with relatives and friends, then finally settling in a small shotgun cottage at 385 First Street. This was a tough but integrated area (not unusual in the New Orleans of the time), populated mostly by German and Irish laborers who seemed to have little trouble getting along with their black neighbors. Mrs. Bolden made a modest living there as a laundress, earning enough to allow her two young children to stay in school without working themselves.

For a ten-year-old boy with a yet-unrealized musical gift, working-class New Orleans in the 1880s was an auspicious place to grow up.

Music was everywhere around him, and thanks to the cosmopolitan nature of the city’s population, it was as varied as it was ubiquitous. Peddlers in the alleys advertised their wares by blowing riffs on old tin horns; “spasm bands” of children, wielding cigar-box banjos and soapbox basses, played tunes for handouts on street corners; Latin and Caribbean songs spilled from the decks of ships at anchor on the wharves. In that age before radio, events like parades and picnics were the everyday diversions, and each one came with its own performing brass bands. Churches, meanwhile, reverberated with hymns and spirituals, dockworkers sang work songs and blues, and even funerals were held with a complete musical accompaniment.

“

The city was full of the sounds of music,” one old-time New Orleanian remembered. “It was like a phenomenon, like the Aurora Borealis.… The sound of men playing would be so clear, but we wouldn’t be sure where [it was] coming from. So we’d start trotting, start moving—‘It’s this way!’ ‘It’s that way!’… Music could come on you anytime like that.”

Despite being surrounded by this feast of sounds, however, young Bolden apparently had no musical training until about 1894, at the age of sixteen or seventeen. That was when his mother allowed him to take

cornet lessons from a neighbor named Manuel Hall, a short-order cook who was keeping company with her at the time. It was a late start for a musician, but Buddy learned quickly. He also had

plenty of opportunities to play: The city’s established brass bands—groups like the

Excelsior, Onward, and Eureka bands—would sometimes work long days, playing funerals or association affairs that stretched from early morning to very late at night. The older musicians would need a break now and then to have a beer or simply to rest their chops, and teenagers like Buddy would fill in for them. By 1897, though, he was already playing with his own regular band at parades and picnics. And despite (or maybe because of) his lack of formal training, he was soon attracting attention by “

ragging the hymns, street songs, and dance tunes to create a musical sound that people were unfamiliar with.”

The Bolden sound, to hear witnesses describe it, was

hot, wide-open, low-down, and—like his most ardent fans—“

ratty.” It was bluesy and folksy, “music that [made] you want to dance.” Like many Uptown black musicians, Buddy couldn’t read music very well, but that didn’t matter much, since he could pick up anything he needed by ear. “

He could go and hear a band playing in the theater,” one old friend recalled, “and he come on out and practice in between dances, and that morning, before the ball was over, he play that piece and play it well.” And it wasn’t only other bands he borrowed from. According to another contemporary, Bolden got ideas from everywhere—from what he heard in the “Holy Roller” churches he sometimes attended with his mother and sister, or even from the man peddling rags with his tin horn: “

Buddy, he stole lots of things from the rag man,” one friend confessed. But each time, he’d “put his own feeling to it,” and thus make it his own.

And the music he made was electric. It was showy, improvisational, sometimes raunchy, and always very, very loud: “

Bolden would blow so hard,” one musician claimed, “he actually blew the tuning slide out of his cornet and it would land twenty feet away.”

This, of course, is a physical impossibility, but it was only one of the legends that eventually grew up around

the Bolden persona. Young Buddy did not, for instance, publish a scandal sheet called

The Cricket

, and he was not a barber. He did, however, spend a lot of time in barbershops, as did many of the early jazzmen, since the shops were common rendezvous points for musicians assembling personnel for upcoming gigs. At Charlie Galloway’s barbershop on South Rampart Street in the late ’90s, Bolden—still in his teens—got many of his earliest jobs. Working by day as a laborer and occasional plasterer, he would play by night in the neighborhood halls and honky-tonks. And

the Bolden Band was soon attracting plenty of attention—and spawning a raft of imitators.

Even some of the older musicians took notice. Bandleaders like Galloway, Edward Clem, and Henry Peyton had already been making some innovative music when Bolden came up, but Buddy took the music in new directions. “

Buddy was the first to play blues for dancing,” one fellow musician said, summing it up. Bolden was also one of the first New Orleans musicians to perform

improvised solos, or “rides.” “

With all those notes he’d throw in and out of nowhere,” another musician said, “you never heard anything like it.” But it was the younger musicians in particular who were picking up the new sound. Not just other cornetists, but clarinetists, trombone and bass players, drummers, and guitarists. Musicians like Freddie Keppard, Bunk Johnson, George Baquet, Pops Foster, “Big Eye” Louis Nelson, Willie Cornish, Frankie Dusen, even a young Creole pianist (something of an outsider among the Uptowners) named Jelly Roll Morton … all were soon doing their own innovations, taking old tunes—or making up new ones—and stamping them with their own personalities.

What exactly were they all playing?

Critics would argue for decades about what the new music actually was. They traced its lineage to African, Caribbean, French, and/or Spanish roots, to ragtime, to various religious forms, and to secular traditions like the blues. But in a way, it was utterly new—music created by largely untrained musicians without much experience in any formal tradition: “

That’s where jazz came from—from the routine men, ya understand—the men that didn’t know nothin’ about music. They just make up their own ideas.”

Perhaps guitarist Danny Barker summed it up best: “

Who cared if you read music? You were free: free to take liberties, free to express yourself from deep inside. The public was clamoring for it!”

Many who heard him claimed that Bolden actually wasn’t a very skilled player technically. “

He wasn’t really a musician,” trombonist Kid Ory once said of him. “He didn’t study. I mean, he was gifted, playing with effect, but no tone. He just played loud.” But that loud, piercing horn helped him break the music free from the more reined-in style of his predecessors,

bringing the soloist—that is, himself—to the fore.