Empire of Sin (34 page)

Authors: Gary Krist

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #True Crime, #Murder, #Serial Killers, #Social Science, #Sociology, #Urban

The mass meeting stretched on into the night, with speaker after speaker reiterating the new unanimity among the city’s righteous citizens to finally demand action of their elected officials. At the end, a vote was taken on whether the Citizens League should submit a full report on vice conditions to District Attorney Luzenberg. It passed without a single negative vote. “Take it to the district attorney,” one speaker concluded, “and tell him if he don’t do his duty, you’ll kick him out!”

Whether Tom Anderson’s crown would finally be taken from him remained to be seen. But as one reporter later put it, it was now clear “

that the most serious and hopeful reform movement of this generation in New Orleans had actually begun.”

A

ND

, miraculously, the city really did respond, and promptly.

CITY WILL CONTROL SEGREGATED AREA UNDER NEW SYSTEM

read the headline in the

Times-Picayune

of January 24. Commissioner Newman, acting with the grudging acquiescence of Mayor Behrman, had announced sweeping new measures to “

drop the lid” on Storyville and the adjacent Tango Belt. For one thing, the city imposed a new ban on cribs in the District. No longer would prostitutes be allowed to rent these places (at exorbitant rates) by the hour or day; the women must hereafter actually live in these structures in order to practice their profession from them. Moreover, any prostitutes living outside the boundaries of the Tenderloin would immediately be evicted, even if their workplace was within the District. As for the cabarets and saloons of Storyville, Newman would refuse to renew their licenses once they expired, so that the places could be closed for good. Until that time, he would revoke their permits for music and for staying open all night. “

The cabarets as they have been conducted in the cabaret district, and as legal institutions, are impossible,” the commissioner announced. A simple sandwich would no longer serve as a way of getting around the Gay-Shattuck Law. In order to operate and serve drinks, a cabaret or dance hall “

must have a licensed restaurant attached.” And to ensure that these goals were actually accomplished, Newman would take personal command of the city’s police department until further notice.

But the edict that would change the culture of Storyville more than any other was Newman’s order for the total racial segregation of the District. Going well beyond the requirements of Gay-Shattuck, the order would require all “Negro inmates” to vacate the neighborhood by March 1 and reestablish themselves in the Uptown district that had come to be known as Black Storyville. Even customers would be segregated under the plan. “

The appearance of a white man in the Negro district will cause his arrest,” Newman decreed, and “should a Negro woman even stroll in the white district, she will be jailed.” As for the famous octoroon houses of Basin Street, they would either move or be closed, since the word “Negro” in New Orleans now meant any person with even a trace of African blood, whether self-described as black, Creole, or octoroon.

This was, needless to say, an extreme measure. Until now, Storyville had been more or less an oasis of relative racial tolerance. Granted, the District had not been entirely immune to the prevailing mood of racial regimentation; by 1908, for instance, the listings in the Blue Books, formerly separating prostitutes into “white,” “colored,” and “octoroon” categories, had begun

describing the women only as “white” or “colored.” But the attraction of the mixed-race brothels had apparently not diminished significantly. This lingering appeal, in fact, was the source of much of the wrath against Storyville from reformers like Philip Werlein, for whom the idea of interracial contact seemed far more objectionable than that of legalized prostitution. But now, Basin Street as an affront to white racial purity would be a thing of the past. And when in February the city council

unanimously passed Ordinance 4118, Newman’s edict officially became city law. Beginning on March 1, Storyville—and Basin Street in particular—would become a very different and very segregated place.

For Tom Anderson, the racial segregation of the District would not be particularly onerous. His extensive interests in Storyville brothels were virtually all white-only (and there is some evidence that Anderson, Mayor Behrman, and other Ring politicians allowed Newman to go ahead with his plan because they thought it would mollify reformers without actually closing the legal district). But for important Storyville figures like Lulu White, Willie Piazza, and Emma Johnson—with their large investments in brothels founded on the trafficking of interracial sex—the new law promised to be financially disastrous. White, Piazza, and a score of other madams and prostitutes immediately

filed suit against the city, attacking the ordinance on constitutional grounds. They claimed that it denied their rights to equal protection under the law and discriminated against them—not on the basis of where they lived, but rather on their employment outside the home. Surprisingly, the court initially upheld these petitions, and when the March 1 deadline arrived, many were allowed to remain in Storyville pending the outcome of their legal actions (though not without first being arrested).

But events in the greater world would soon render all of these cases moot. On April 6, 1917, the United States officially entered the war in Europe. Mayor Behrman and New Orleans’ business leaders, hoping to attract federal dollars and visitors to the city,

lobbied to host a military encampment within city limits. Their effort succeeded, and doughboys were soon pouring into Camp Nicholls in City Park. As hoped, this influx proved to be a boon to the local economy—not least of all in Storyville, given the proclivities of young soldiers. But it also put the city at the mercy of the US Department of War. And the

federal government in times of war had powers that social reformers could only dream of. Before summer arrived, Congress would pass a law that—more than any local reform effort ever could—would threaten the very existence of the twenty-year-old legalized district, leaving the city little choice but to close its famous tenderloin entirely.

Storyville, in other words, was now truly under siege. But it would not go down without a final fight.

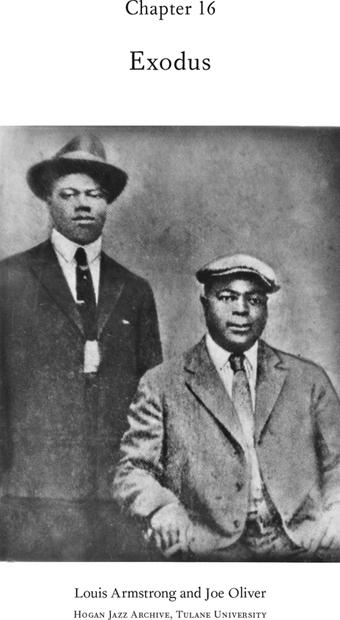

LITTLE LOUIS ARMSTRONG NEEDED MONEY.

EVER since the shooting incident at Henry Ponce’s honky-tonk, the place had been closed down, meaning that Louis had lost his best and most regular paying gig. The recent reform efforts to suppress the city’s cabarets, meanwhile, had made other engagements harder to come by. Armstrong still had his job making deliveries on the coal cart (pulled by an amiable mule named Lucy), and

Mayann had started working as a domestic for club owner Henry Matranga, but it wasn’t enough. Not long before, one of Mayann’s second cousins had died after giving birth to an illegitimate son, Clarence. Louis, though still in his teens, had decided to take financial responsibility for raising the boy (

he would later adopt him). So now there were four mouths to feed in their little household, and Louis was feeling the pressure to earn.

So he thought he might try his hand at a slightly different kind of business. “

I had noticed that the boys I ran with had prostitutes working for them,” he later recalled. “I wanted to be in the swim, so I cut in on a chick.” The chick in question was named Nootsy, and although she was hardly a great beauty—she was “short and nappy-haired and she had buck teeth,” according to Armstrong—she made decent money. Of course, it’s questionable how much value a shy, peaceable teenager could be to her as a pimp, but Nootsy apparently took to him immediately. One night she even invited him to share her bed. Louis, who admitted being a little afraid of “

bad, strong women,” demurred. “

I wouldn’t think of staying away from Mayann and Mama Lucy,” he told her, “not even for one night.”

“Aw, hell,” Nootsy replied. “You are a big boy now. Come in and stay.”

But Louis still refused. In a fit of pique, Nootsy grabbed a pocketknife and plunged it into her new pimp’s left shoulder. He retreated in a panic, planning to say nothing about the incident. But when he got home, Mayann saw the blood on his shirt and coaxed the story out of him. Enraged, she pushed her son aside and marched right over to Nootsy’s crib, with Louis and several of his neighborhood friends following behind. She pounded on the door, and the moment Nootsy opened it, Mayann grabbed the prostitute by the throat. “What you stab my son for?” she shouted.

Fortunately, Black Benny was among the witnesses to this spectacle. “Don’t kill her, Mayann,” the drummer pleaded, pulling her off the traumatized woman. “She won’t do it again.”

“Don’t ever bother my boy again,” Mayann spat, still furious. “You are too old for him. He did not want to hurt your feelings, but he don’t want no more of you.”

So much for that experiment in income supplementation. But Louis still had his music to fall back on, though even on the bandstand he was not invariably successful. He was still a relative beginner on the cornet, and despite his substantial raw talent, his repertoire was limited. This fact became painfully clear when he was asked to sit in for his mentor on a gig. Joe Oliver, it seems, had taken up with a woman named Mary Mack and only had the opportunity to visit with her from eight to eleven in the evenings. Oliver asked violinist Manuel Manetta and trombonist Kid Ory, whose band he was playing with, whether Louis could substitute for him during those hours. They agreed, but discovered that the protégé did not have the drawing power of his mentor. According to Manetta, Louis knew how to play only three tunes at this time, which the group would have to play over and over again, to an almost empty house. “

People lined up outside,” Manetta recalled, “but not a soul came in the hall”—until, that is, Oliver returned from his tryst at eleven

P.M.

, and the crowd flooded in like the Mississippi River rushing through a levee breach.

Part of the problem could have been Armstrong’s style, which may have been a little too advanced for these early jazz audiences. Louis played in a freer, highly improvisational manner, tracing a complex melodic line more like a clarinet’s obbligato than the lead cornet’s usual, relatively straightforward, statement of the tune. (“

I’d play eight bars and be gone,” he later admitted. “Clarinet things, nothing but figurations and things like that … running all over a horn.”) Oliver once even criticized the boy for this. “Where’s that lead?” he asked Louis one night after hearing him perform in a honky-tonk band. “You play some lead on that horn, let people know what you’re playing.” But Armstrong was already taking the sound pioneered by Bolden and moving it in new directions. Audiences—not to mention his fellow jazzmen—would eventually catch up.

The increasingly oppressive atmosphere in New Orleans, however, was making some of Armstrong’s colleagues—like Sidney Bechet—yearn to get out of the Crescent City and try their luck elsewhere. Certainly Bechet wasn’t hurting for work; in recent years—making good on the astounding versatility he’d displayed as a child at Piron’s barbershop—he’d been

developing his skills on other instruments. He’d learned to play the cornet (to pick up work with marching bands) as well as the saxophone (a relatively new instrument that had yet to make much impact in New Orleans). Even so, he was still impressing audiences primarily as a clarinetist. For his occasional gigs at Pete Lala’s,

he’d learned George Baquet’s old trick of taking his clarinet apart as he was playing it. Whenever he’d perform the stunt, gradually disassembling the instrument until he was tootling away on the mouthpiece alone, the crowds would respond with enthusiastic glee. “

Mr. Basha [

sic

] is screaming ’em every night with his sensational playing,” one black newspaper wrote, about a series of performances at New Orleans’ Lincoln Theatre. “Basha says, look out, Louis Nelson, I am coming.”