Empire of Sin (42 page)

Authors: Gary Krist

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #True Crime, #Murder, #Serial Killers, #Social Science, #Sociology, #Urban

As if in answer to these questions, the axman soon made his presence felt again. At

3:15

A.M.

on Sunday, August 4—in a house at 2123 Second Street, virtually around the block from the Uptown residence in which Buddy Bolden had lived for much of his life—a scream again rent the silence of a summer night. Sarah Laumann, a nineteen-year-old woman asleep in her parents’ house, woke in pain to find someone looming over her in the bedroom. “

I felt a stinging of the left ear,” she later explained, “[and] I saw a man standing over me under the mosquito bar …” That’s when she screamed, and the man bolted away, scrambling out an open window. By the time her parents had rushed into her room from their own bedroom next door, the intruder was gone.

But had he been the axman? There was no blood in the bed, and Sarah Laumann didn’t even realize she was injured until several hours later, when she found a small but painful laceration behind her left ear. Was this the result of a glancing blow from an ax that had perhaps gotten tangled in the mosquito netting? (One wonders how many ax victims’ lives were saved by this ubiquitous New Orleans necessity.) But Laumann had seen no ax held by the man standing above her bed. Hours later, an ax was found under the school building next door, which was under repair, but it had no bloodstains on it. And the Laumanns, unlike so many other victims, were not grocers, Italian or otherwise. And yet Sarah’s description of her white assailant matched that of the Bruno girl in the Romano case a year earlier: “

He was about five feet and eight inches tall,” she told police, “had a dark complexion, weighed about 160 pounds, [and] wore a cap pulled down over his eyes, dark coat and pants, and a white shirt with dark stripes.”

Axman attack or not, the Laumann incident set off yet another round of hysteria throughout the city. Less than a week later, a grocer named Steve Boca stumbled to the door of a neighbor on Elysian Fields Avenue with a bloody gash in his head and no idea what had happened to him. Police discovered that his house had been broken into via a chiseled-out panel in the back door. A bloody ax had been left on the kitchen floor. Then, on September 2,

a druggist named William Carlson, lying awake reading, heard sounds coming from his back door. Panicking, he called out a warning, but when the noise continued he fired a shot at the closed door with his revolver. When he worked up the courage to open the door, he found that one of its lower panels had been scored with chisel marks.

By now, the people of New Orleans seemed prepared to believe that the axman was everywhere, and that Mooney and his police could do nothing to stop him. This became terrifyingly apparent when, on the night of October 27, Deputy Sheriff Ben Corcoran, returning late to his home on Scott Street in Mid-City, heard yet another scream coming from yet another Italian corner grocery. He ran to the end of the square and found eleven-year-old Rosie Pipitone out on the street, “

bellowing that her father was full of blood.” When he entered the premises, he found Mrs. Michael Pipitone, whom he knew as a neighbor, distraught and near hysteria. “Mr. Corcoran,” she wailed, “it looks like the axman was here and murdered Mike.”

The crime scene was by now sickeningly familiar. Mike Pipitone lay in a gore-soaked bed with a fractured skull and the entire left side of his face beaten in. This attack had apparently been particularly savage. Bloodstains spattered the bedroom walls to a height of eight feet. The obvious murder weapon lay on a chair beside the bed. But it was not an ax or a hatchet; it was

a foot-long thick iron bar with a large iron nut screwed to its end.

Mike Pipitone, rushed to Charity Hospital, died there at 3:15

A.M.

of massive hemorrhaging in the brain. Later, after Superintendent Mooney and Detective Long had arrived on the scene, Mrs. Pipitone explained what had happened. She had been sound asleep until she heard her husband’s cries in the darkness beside her. “

Someone was calling me,” she told them. “The cry seemed to get louder and nearer and suddenly I opened my eyes and I heard my husband say, ‘Oh, my God!’ That is all he said. And then I saw the forms of two men. I could just see the outlines of their figures as they hurried from our room into the children’s room and disappeared in the darkness.”

“I turned to my husband,” she continued. “What I saw terrified me. Every time he turned his head, blood came from his head and face. It simply poured over the bed.” That’s when she jumped up, ran into the dining room window, and began to scream for help.

This was another horrifying crime, but again, as in the Laumann case, it seemed questionable whether this was indeed an axman assault, for several reasons. Most obvious of them: the murder weapon was not an ax. The means of entry—through a smashed side window—was another atypical element in the axman repertoire. And Mrs. Pipitone seemed certain that she had seen

two

men, not one, fleeing in the darkness. In fact, if not for her initial remark to the deputy sheriff—not to mention the ongoing serial-killer obsession in the city—one wonders whether the deed would have been considered an axman crime at all.

Mooney’s detectives eventually turned up a different intriguing possibility,

linking the Pipitone murder to the rash of Mafia killings that had broken out in the years following the Lamana kidnapping in 1907. The 1910 shooting of Paulo Di Christina, after all, had been laid at the door of Mike Pipitone’s father, Pietro (at the time, some detectives had even believed that Mike actually did the shooting). Now free on parole for that crime, the senior Pipitone had been in the house when his son was killed. But although the police questioned him and numerous others involved in the Di Christina murder—including all of the attendees at Mike Pipitone’s funeral—they could find no connection to the current crime. When asked by a

Times-Picayune

reporter whether Mooney had any theory to explain the apparent coincidence, the superintendent frankly admitted “

that the police have not the slightest clue.”

It was, in any case, to be the last alleged axman crime. Several suspects were arrested for one or another of the ax crimes over the next weeks, but all eventually had to be released for lack of evidence. And as time passed without another ax attack, the hysteria in the city subsided. Even the Jordanos, convicted in the Cortimiglia case, were ultimately released. Young Rose Cortimiglia apparently had a nighttime visitation from Saint Joseph, who urged her to clear her conscience before she died. She subsequently recanted her testimony against the Jordanos. “

Everyone kept saying to me that it was them,” she explained, and so she began to believe it. “I was not in my right mind.” But now she claimed to understand the seriousness of her false accusation, and she apologized to her erstwhile neighbors. “

God, I hope I can sleep now,” she told the judge, who, after some procedural difficulties, managed to get the convicted murderers released.

And so even this one “solved” ax crime became unsolved once more. But although there would be no more murders in the night, the shadowy axman would claim one more victim. Superintendent of Police Frank Mooney, under

continuing criticism for his inability to solve the murders, was eventually forced to resign in late 1920. He went back to the job he did best—running a railroad, which he did

in the wilds of Honduras until his death after a heart attack in August 1923.

But the axman ordeal did have a final chapter. Late in 1921, New Orleans police would learn something that would shed new light on the long series of attacks, pointing to one well-known career criminal who might have been responsible for the mayhem (see Afterword). In the meantime, the case remained unsolved, and the city seemed to forget about its nemesis. Order had been restored to the streets, and the city had returned to its more circumspect postwar self. The ever-conservative

Times-Picayune

seemed positively delighted by the quieter, more respectable atmosphere. After New Year’s Day of 1920, the paper could report on an admirably sober observation of the holiday.

PUNCTILIOUSNESS, PRIMNESS, AND PRUDERY PREVAIL HERE

read the headline in the January 2 issue, over an article about the tameness of the usually raucous celebration. “The first day of the new year was observed, rather than celebrated,” the paper reported, “with hushful, Sabbatical ceremony …[New Orleanians] paraded with dignity and aplomb, feeling that they looked as virtuous as they felt.” Casualties were few, and arrests were “practically nil.”

But the reformers—though clearly in the ascendant—were not finished with the city quite yet. There was, after all, still one symbolic figure who had survived this triumph of supposed virtue in New Orleans. Tom Anderson, the erstwhile mayor of Storyville, was still sitting in his seat of power in the state legislature. In order for the reform revolution to be complete, many felt that this situation had to be rectified. Tom Anderson—and the political machine that supported him—would have to be destroyed entirely.

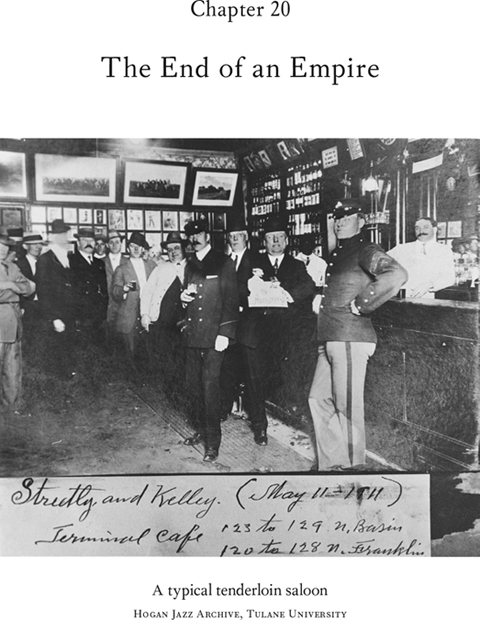

BY 1919, TOM ANDERSON’S EMPIRE WAS IN SIGNIFICANT disarray. With the closing of the restricted district and the failure of the resulting lawsuits to overturn the decision, Anderson’s business interests were suffering. For a time, he and the other vice lords of New Orleans had hoped that the end of the world war might derail the juggernaut of wartime puritanism, but the hectoring had only grown more insistent over time. Reform groups like the Citizens League had not backed down a bit after the Armistice. In fact, they were now putting so much pressure on city officials that even a police force still largely under Ring control had been forced to respond with aggressive enforcement efforts.

As a result, the vice underworld of the city was not so much collapsing as fragmenting, dispersing,

going truly underground. Open brothels were now largely a thing of the past, replaced by discreet assignation houses, call girls with pimps, and temporary cribs that would have to close down the moment some meddling preacher got wind of their existence. Those who tried to operate in the old ways now paid a price, as some of the formerly prominent madams soon found out. Lulu White and Willie Piazza, for instance, were

each arrested at least once in the immediate post-Storyville years, and Anderson’s consort, Gertrude Dix, even had to spend a short time in jail for trying to operate her brothel. Of course, vice was still alive in the city—as Mayor Behrman once famously remarked,

“You can make prostitution illegal in Louisiana, but you can’t make it unpopular”—but as a business proposition, it was becoming less and less tenable.

Meanwhile, Tom Anderson’s share of even this diminished market was shrinking. He had begun downsizing his vice holdings as early as 1907, when he

sold his tony restaurant the Stag to Henry Ramos (already famous as the inventor of the Ramos Gin Fizz). In 1918, disgusted by his failure to save Storyville, he had divested himself of the district’s so-called city hall—the Annex on Basin Street, which he

turned over to his longtime lieutenant, Billy Struve. Even his

stately home on Canal Street was no longer his own; he’d given it to his daughter, Irene Delsa, so that she and her husband could raise his grandchildren in comfort (albeit with the agreement that Anderson could still use it for entertaining and political business). Now he lived modestly in an apartment on Rampart Street, a few doors down from his sole remaining vice headquarters, the Arlington, the establishment with which he had begun his empire in the 1890s. And even here he wasn’t left alone, with police pestering him continually for alleged violations of one law or another. Staying in business now required constant vigilance, not to mention an untold number of favors called in to make the violations disappear. For the former mayor of Storyville, the situation was downright humiliating.

But the city’s reformers were still far from satisfied. Their ultimate goal was to end the entire era of Ring rule—not just in New Orleans, but at the state level as well. And they knew that the way to do this was to focus their attacks on a symbol of Ring turpitude who could be used as an example to discredit the entire organization as the 1920 elections approached. That symbol, naturally enough, turned out to be Representative Thomas C. Anderson, now serving his fifth term in the state legislature. If they could accomplish the total demolition of Anderson, they reasoned, Martin Behrman and the entire Ring could be toppled—first in the state elections, which were to take place in early 1920, and then in the New Orleans municipal elections at the end of that year.

This new reform offensive began in late 1918. From pulpits and lecture halls around the city, orators tirelessly pounded away at Anderson and his Ring supporters. As they did before the closing of Storyville, Jean Gordon and William Railey of the Citizens League fulminated at length before large crowds, demanding that officials take Anderson to task for his flagrant disregard of the Gay-Shattuck Law. “

Why was Anderson never prosecuted for repeated violations of this law?” Railey asked in an open letter to the

Times-Picayune

. “Was the district attorney ignorant of a fact that was well known all over town?… The police are not such boneheads as not to know where gambling and prostitution are being carried on when it is well known to the public. [But DA] Luzenberg doesn’t act; [Superintendent] Mooney doesn’t act; the police board doesn’t act and the mayor doesn’t act. What is the remedy for this carnival of gambling and law violation that is openly carried on in our city every day?”