Empress of Fashion (15 page)

Read Empress of Fashion Online

Authors: Amanda Mackenzie Stuart

Yearning in wartime:

Harper's Bazaar

cover, September 1943. (Photographer: Louise Dahl-Wolfe)

Â

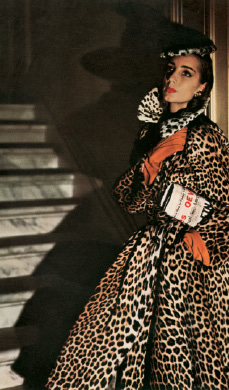

Anxious in wartime: model in coat by Traina-Norell, outside the Wildenstein Galleries, New York, October 1943. Styled by Diana. (Photographer: Louise Dahl-Wolfe)

Â

Lauren Bacall en route to fame:

Harper's Bazaar

cover, March 1943, styled by Diana. (Photographer: Louise Dahl-Wolfe)

Â

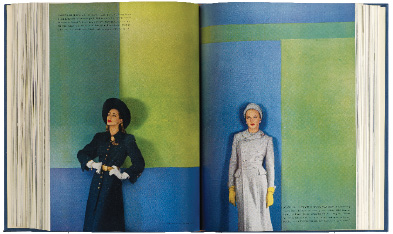

Harper's Bazaar

, March 1946: “Shipshape in navy . . . wool buttoned bang down the middle with high-sheened gilt,” by Nettie Rosenstein; “Shipshape in gray . . . wool jersey buttoned bang up one side with polished sterling silver,” by Traina-Norell. (Photographer: Louise Dahl-Wolfe)

Â

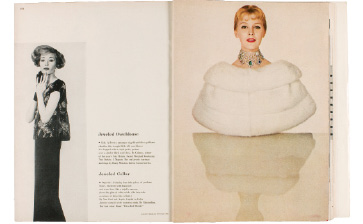

Harper's Bazaar

, October 1956. Jeweled overblouse: “A flowery armature of gold-and-silver paillettes” by Galanos. Jeweled collar: “Clustered with diamonds and worn here like a rajah's ransom above the glint of white mink.” Collar: Van Cleef & Arpels. Mink capelet: Maximilian. (Photographer: Louise Dahl-Wolfe)

Â

Diana Vreeland with model, on set for

Harpers Bazaar

, New York, 1946. Photographer: Richard Avedon © 2011 The Richard Avedon Foundation.

Pizzazz

I arrived at

Harper's Bazaar.

I came in on a Monday. . . . I was given a tiny office. I was sitting in my office talking to myself. I kept saying, “I work here! I work here!”âI couldn't believe it.

George Davis, the fiction editor, stuck his head around her door and said: “What this country needs is Bob Hope.” Then he disappeared.

I didn't know one thing. I didn't know who Bob Hope was! My God, when I think of what I didn't know, of what I had to learn.

It was all very puzzling.

After a few days had gone by, I made friends with the Managing Editor, a divine woman named Frances McFadden. And I said to her, “I've got to tell you somethingâI do stay up rather late at night and I just can't do without lunch.”

“Well,” she said. “Why should you?”

“But there's no time for lunch, is there?” I said to Frances.

“Of course there is. Why don't you just have lunch?”

T

he strange new world in which Diana found herself in 1936 was all the more interesting because

Harper's Bazaar

was undergoing a transformation.

Bazaar

first emerged as an upstart competitor to

Vogue

when it was bought by William Randolph Hearst in 1913, but it only became a serious threat once Hearst started poaching

Vogue

's staff. Three years before Diana arrived, Hearst pulled off a great coup by luring her new boss Carmel Snow to

Bazaar

. Snow had been heir apparent to

Vogue

's formidable editor in chief, Edna Chase. She had begun her career by working in the dress shop of her domineering Irish mother, who made copies of French designs for rich New Yorkers. By the time she was in her early twenties, Snow knew everything there was to know about sewing and tailoring, French couture, and smart customers. But her own stylish flair, her omnivorous interest in much beyond fashion, and her desire to write brought her to the attention of Chase, who set about training her. Snow served a long apprenticeship as Chase presided over some radical changes at

Vogue

, including the shift from line drawings to fashion photography; and by 1929 Chase was so busy supervising international editions of

Vogue

that Snow became editor of American

Vogue

, while Chase herself became editor in chief. Condé Nast and Edna Chase both adored Snow, making their sense of betrayal when she left for

Bazaar

all the greater. In the end, however, her decision to defect was not surprising. Chase was a frustrating boss who became more autocratic with every passing year. Her rigid ideas about chic extended to every aspect of life. And although she kept promising to retire and make way for Snow, she never did.

Released from the oppressive atmosphere of Mrs. Chase, Carmel Snow came into her own. Within two years of arriving at

Bazaar

in late 1932 she had transformed a dull and musty magazine. She sacked the fashion department; appointed herself the temporary art director; and implemented lessons learned at Condé Nast Publications, operating at a peak that lasted until the late 1950s. During the week she left her three children with a nanny on Long Island, and she and her husband led separate lives. A slight woman, with an upturned nose, a face that reminded Beaton of a fox terrier, and hair that was almost blue, Snow never lost the Edna Chase habit of wearing a little hat and pearls to work but that was where the similarity ended. She was warm, funny, full of life, and open-minded. At the same time, her soft Irish lilt was deceptive, for she was much tougher than she looked or sounded. She was determined, rigorous, discerning, even ruthless in her search for quality. She believed that

Bazaar

had to startle and surprise and at her best, she was very bold. She was keenly aware that

Bazaar

could only succeed by being daring in a way that

Vogue

was not. She had a gift for spotting gifted people; and she was extremely good at creating a stimulating, disciplined atmosphere in which they flourished.

One of Snow's early breakthroughs at

Bazaar

came when she noticed the work of the Hungarian photographer Martin Munkácsi. She had developed a keen understanding of the importance of fashion photography at

Vogue

, where she had worked closely with its innovative, irascible art director, Mehemed F. Agha (always known as “Dr. Agha”), and

Vogue'

s chief photographer, Edward Steichen. At

Vogue

the work of Steichen, Beaton, and others not only brought art to fashion but also had a profound impact on fashion itself, making it possible for readers like Diana to see new designs with far greater clarity. These images captured the independent, confident atmosphere of the New Woman of the 1920s, and extended the public space she inhabited while creating a fantastic, soft focus world of “real” but impossible glamour. On arrival at

Bazaar

, Snow was dismayed by the work of its house photographer, Baron Adolph de Meyer, whose ornate, romantic style had changed little since the early twentieth century. But she could find no satisfactory alternative until she came across Martin Munkácsi, a news photographer with an interest in sports who had never taken a fashion picture in his life.

“I decided that I had to let him re-photograph a bathing-suit feature that had been taken, as usual, in the studio against a painted backdrop,” she recalled. Together they came up with the idea of taking the swimsuit model to the beach at Piping Rock Club on Long Island on a cold November day. Here, to general astonishment, Munkácsi directed the model to run toward him as he photographed her with a sports camera, a 35 mm Leica. The resulting picture of the model running along the beach with her cape billowing out behind her became a defining image of the active American girl. It was also, said Snow, “the first action photograph made

for fashion

.” (It made such an impact on Diana at the time that she later put it in

Allure

.) Snow immediately dropped de Meyer and allowed Munkácsi free range, starting a new direction in fashion photography that connected high fashion with action, on location. Munkácsi's photographs were dismissed by Edna Chase as “farm girls jumping over fences,” but they made

Bazaar

look modern and exciting at

Vogue

's expense.

In a move that was even more farsighted, Snow hired Alexey Brodovitch, a designer of outstanding brilliance, in 1934. Russian by birth, Brodovitch had come to the United States by way of every European artistic movement of the early 1920s. Forced into exile during the Russian Civil War, he had made his way to Paris, where he found himself at the center of dadaism, constructivism, Bauhaus design, futurism, surrealism, cubism, and fauvism, working first as a backdrop painter for the Ballets Russes before becoming a highly successful graphic designer. In 1930 he moved to the United States to work at the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art and subsequently became head of its Advertising Design Department. An outstandingly good teacher, he set about pulling American advertising up to European standards while continuing to produce radically innovative work of his own. Snow spotted some of his work at an exhibition of advertising design run by the Art Directors Club of New York and, with her unfailing instinct, knew she was looking at the work of someone extraordinary, with the potential to become a great magazine art director. Without Hearst's authority she persuaded Brodovitch to sign a contract with

Bazaar

on the spot. She then flew to see Hearst at San Simeon in California and persuaded him, most uncharacteristically, to approve a fait accompli.

As art director, Brodovitch transformed the look and feel of

Bazaar

and, ultimately, most American magazines. He was not the first to introduce Bauhaus-inspired design to the pages of a magazine, since Dr. Agha was already doing this in a more modest way at

Vogue

. Agha may also have been the first to tilt type, to allow white space on the page, to “bleed” photographs to the edge of the page, and to spread images into fan shapes. But Agha was limited in what he could achieve by Edna Chase, who could see no relationship between form and content. Snow was quite the opposite. She was decisive; she was very much in charge; but she had a gift for collaboration. She and Brodovitch worked together closely so that crisp, snappy titles and editorial content conceived by Snow worked in a unified way with Brodovitch's graphic design and modernist typefaces. Snow encouraged Brodovitch to be daring, to use type to compose arresting graphic shapes on huge white spaces, even permitting him to experiment with cellophane overlays that changed the image of the page beneath. Their most significant innovation was inspired partly by Brodovitch's love of ballet and partly by film montage. They developed a way of working together in which they laid out each issue of

Bazaar

on the floor of Snow's office, with the aim of introducing a sense of cinematic movement through its pages, juxtaposing the close-up with the wide shot and placing tranquil content next to more exhilarating material.

Bazaar

became, to quote Calvin Tomkins, “a monthly run-through of popular and high culture with its own ebb and flow, cadence and rhythm,” a magazine that captured the dynamic quality of 1930s modernity.

As Emily Dalziel's article about her safari in Africa attests,

Bazaar

had always covered more than fashion. Once she became editor, Snow took this further, projecting her wide-ranging interests onto every issue in a way that has led her to be described as the first “magazine editor as auteur.” She conceived of the magazine precisely as a kind of “bazaar” where exotic items jostled for space, and she famously dubbed it a publication for “the well-dressed woman with the well-dressed mind.” She reeled in Jean Cocteau very early; she recruited the illustrator Marcel Vertès whom she found working for Schiaparelli; she published the first fashion drawing by Salvador DalÃ; and fashion photographs by Man Ray. She was a voracious reader. There were none of

Vogue

's restrictions on publishing fiction at

Bazaar

and, unusually for a Hearst magazine, fiction writers were paid well. With the help of Beatrice Kaufman, the wildly unpredictable George Davis (who put his head around Diana's door on her first morning), and several others,

Bazaar

became a vehicle for some outstanding twentieth-century writing. Snow poached Frances McFadden from

Vogue

to become

Bazaar'

s managing editor, and she took in other refugees from Chase's regime, including one of

Vogue

's star photographers, George Hoyningen-Huene. The

Bazaar

office was small, housed on two floors of a former hotel at 572 Madison Avenue. It bore little resemblance to the stately premises of Condé Nast Publications, but it hummed with excitement. In the end

Bazaar

never overtook

Vogue

in terms of circulation. But, as Calvin Tomkins has observed, by 1935

Harper's

Bazaar

“seemed yearsâdecadesâyounger.”

C

armel Snow initially hired Diana because she saw her as a stylish representative of the international set; and she introduced her to

Bazaar'

s readers in January 1936 with a Munkácsi action photograph of Diana striding down a New York pavement in a Mainbocher suit and cape, topped off with a Tyrolean cap featuring four sharp feathers (and wearing the characteristic T-strap shoes that were handmade for her odd, seemingly boneless feet until the shoe designer Roger Vivier made a special pump for her years later). Snow had learned at

Vogue

that featuring the lives of chic women from the highest echelons of society was the way to draw in a wider middle-class readership. But many of the most interesting members of American high society had blended with international café society in the 1920s and 1930s, and in her view

Vogue

was failing to capture the special essence of their lives. She was determined to put this right at

Bazaar

. She had already made one attempt at evoking the spirit of the international beau monde by hiring the exceedingly fashionable and exceptionally difficult Daisy Fellowes as Paris editor in 1933, and for a while this arrangement worked surprisingly well. Fellowes's association with

Bazaar

had the effect of putting the magazine on the Paris fashion map, and she mesmerized American fashion representatives, receiving them lying on a chaise longue in peacock blue pajamas. When she decided to wear cotton, she started a trend that earned the eternal gratitude of cotton manufacturers, whose advertising financed

Bazaar

through the worst of the Depression. But in early 1935, after many tantrums, Daisy became bored and she resigned. Snow continued to draw attention to the ideas of society women who were just a little different, commissioning a piece on clans and tartans written by Diana's friend Mrs. Robin d'Erlanger in September 1935. But she did not find a true replacement for Daisy Fellowes until she met Diana.

Once she had offered Diana a job, however, Snow had to solve the problem of what to do with her. It was clear that Dianaâwho preferred to be called “Diane” by her new colleaguesâwas extremely stylishly dressed, that she was fascinated by everything new and interesting, and that she had a way of expressing herself that was all her own. “Diane converses

naturally

(according to her nature), sometimes in poetry, sometimes in startlingly original slang, sometimes in pithy comments that sound like the Sphinx she somewhat resembles,” wrote Snow. But in 1936 what interested her most were Diana's exhilarating observations on the art of living as practiced by international high society; and in the earliest days of Diana's association with

Bazaar

, at least one member of the magazine's staff remembered that Snow simply took down exactly what Diana said and edited it. “She used to come in once a week to talk and the whole thing was that she just gave Mrs. Snow a stream of consciousness,” said Mildred Morton Gilbert, one of her new colleagues. By the time Diana was given her own office, however, Snow had worked out what Mrs. Vreeland ought to do. As editor of

Bazaar

she was extremely good at coming up with bright ideas for articles that connected the middle-class reader to women of high society in a very direct way. In a feature called “I'd Be Lost Without . . . ,” for example, Mrs. William Averell Harriman reported that she'd be lost without her old white raincoat in Bermuda, Mrs. William Deering Howe thought she'd be lost without her traveling radio in a pigskin case, and Mrs. Harrison Williams was sure she'd be distraught without one enormous Mexican straw hat in Palm Beach. Snow now hit on an idea for a column in a similar vein for Diana: a list of suggestions for fashionable living that drew on Diana's six and half years in Europe and her experience of life as it was lived by the international elite

.

Called “Why Don't You?” it caused a greater commotion than any list like it, before or since.