Enemies: A History of the FBI (22 page)

Read Enemies: A History of the FBI Online

Authors: Tim Weiner

On August 14, 1943, Hoover ordered his agents to intensify their search for suspects to be placed on the Security Index, and to ensure that the index was kept secret within the Bureau, hidden from the attorney general. The list of people “

who may be dangerous or potentially dangerous to the public safety or internal security of the United States” was to be shared only with trusted military intelligence officers “on a strictly confidential basis.” “Potentially dangerous” meant people who might have committed no crime beyond political disloyalty.

Generals are often accused of fighting the last war. Hoover was preparing to fight the next one.

Stalin was still America’s most powerful military ally. And Wild Bill Donovan and his intelligence officers at the Office of Strategic Services wanted to work hand-in-glove with the Soviets. But Hoover now refocused the FBI’s Security Index on “

key figures” and “potential key figures” in the

Communist subversion of America, not just card-carrying Party members. Soon ten thousand people were listed in the index—almost all Communists and, to Hoover, potential Soviet spies.

The FBI would have to go it alone, or close to it, for the next two years. But the intelligence battles of the Cold War had begun.

15

ORGANIZING THE WORLD

S

PYING ON THE

S

OVIETS

required spying on Americans. Hoover spied hardest against his enemies within the government of the United States.

Hoover wrote to FDR’s closest White House aide, Harry Hopkins, on February 10, 1944, warning him about Wild Bill Donovan’s scheme to invite Soviet spies to America:

I have just learned from a confidential but reliable source that a liaison arrangement has been perfected between the Office of Strategic Services and the Soviet Secret Police (NKVD) whereby officers will be exchanged between these services. The Office of Strategic Services is going to assign men to Moscow and in turn the NKVD will set up an office in Washington, D.C.…

I think it is a highly dangerous and most undesirable procedure to establish in the United States a unit of the Russian Secret Service which has admittedly for its purpose the penetration into the official secrets of various government agencies …

In view of the potential danger in this situation I wanted to bring it to your attention and I will advise you of any further information which I receive about the matter.

Sincerely,

J. Edgar Hoover

The problem was that the president himself had dispatched Donovan on his mission to Moscow. FDR had sent Donovan and the American ambassador, W. Averell Harriman, to meet with the Soviet foreign minister, Vyacheslav Molotov. They had gone to the Soviet intelligence headquarters

on Dzerzhinsky Street, named after Lenin’s chief of espionage and terror. They met with the chief of Soviet foreign intelligence, General Pavel Fitin, and his deputy. That deputy was Gaik Ovakimian, the same spy who had run Soviet intelligence operations in America for eight years before he was arrested by the FBI in New York and then released at the State Department’s behest in the summer of 1941.

The four toasted the inauguration of the American station in Moscow and the Soviet station in Washington. Stalin swiftly gave his imprimatur.

On January 11, 1944, Donovan went to win FDR’s approval. They sat in the Map Room, the intelligence center at the White House. Donovan pointed out the advantages of intelligence liaison with the Soviets in the war against Hitler, which were significant. As for the question of Soviet spying in America, he told the president: “They are already here.”

The president ran Donovan’s deal past the White House military chief of staff, Admiral William D. Leahy. Bad idea, Leahy said, and he bucked it up to the military chiefs. They told Hoover, and Hoover went to battle. He refused to let the Soviets set up a new intelligence station a few blocks from the White House. He suspected—correctly—that Donovan’s OSS had been penetrated by the Soviets and that one of his top aides was spying for Stalin.

Hoover underscored the threat in a memo to the attorney general, entrusting Biddle with the highly confidential information that Soviet spies were inside Donovan’s domain. Biddle pointed out the implications to the president. First, the Foreign Agents Registration Act would require the Soviet spies to file forms stating their identities. Second, those papers were documents that could be disclosed; public knowledge of the arrangement could have political consequences. And third, as Hoover had warned, the Soviets were trying to steal the biggest secrets of the government of the United States. Admiral Leahy formally told Donovan that the deal was off. Wild Bill had lost a major battle.

Now Hoover began to contemplate taking control of United States intelligence when the war was over. He saw himself as the commander in chief for anticommunism in America. The FBI, in partnership with the military, would protect the nation as it projected its power around the world.

Hoover now commanded 4,886 special agents backed by 8,305 support staff, a fivefold increase since 1940, with a budget three times bigger than before the war. The FBI devoted more than 80 percent of its money and people to national security. It was by far the strongest force dedicated to fighting the Communist threat.

By December 1944, Hoover had defined that threat as an international conspiracy in which the Soviet intelligence service worked with the American Communist Party to penetrate the American government and steal the secrets of its wartime military industries. The FBI already worked closely with British intelligence and security officers in London. As the Nazis retreated, FBI agents had set up shop in Moscow, Stockholm, Madrid, Lisbon, Rome, and Paris. FBI legal attachés established permanent offices at the American embassies in England, France, Spain, and Canada. Hoover’s men investigated the threat of espionage inside embassy code rooms in England, Sweden, Spain, and Portugal; in Russia they looked into the sensitive question of whether the Soviet government was exploiting any part of $11 billion worth of lend-lease aid from the United States to steal American military secrets. In Ottawa, FBI men worked in liaison with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. FBI attachés and their new friends among Latin American police and politicians were creating international networks for a war on communism.

As Hoover put it, “

the system that has worked so successfully in the Western Hemisphere should be extended to a world-wide coverage.” He had to deep-six the history of the struggles of the SIS as he set out his first proposals for taking the FBI global. Only its successes would be made known in Washington.

The FBI continued to find fragments of the immense puzzle of Soviet espionage. On September 29, 1944, FBI agents burglarized the New York apartment of a middle-aged man who worked at a record company selling Communist songs. He went by the name of Arthur Alexandrovich Adams, and he was a skilled mechanical engineer. He had probably come to the United States in the 1920s, and he may have been one of the first deep-cover Soviet spies in America. He was certainly the first one the FBI ever found.

The black-bag job produced a bonanza.

Adams had notebooks that made little sense to the FBI agents who saw them. “

He was in possession of a document that talked about some type of water,” FBI agent Donald Shannon, a member of the Bureau’s Soviet espionage squad, said in an oral history interview six decades later. “We weren’t sure of the information so we turned it over to the Atomic Energy Commission for evaluation.” Upon expert review the notes revealed intimate knowledge of highly technical and deeply secret phases of the Manhattan Project. They included work on heavy water, a linchpin of secret research into the atomic bomb.

“We were informed that the person who had this certainly had some information on America’s atomic research,” Shannon said. Adams soon was indicted by a federal grand jury in New York under the foreign agents registration law—and the State Department ordered him deported.

Eighteen months had passed since the FBI’s first clue that Stalin’s spies were trying to steal the bomb. The second clue was now in hand.

Hoover understood in broad terms what the Manhattan Project was about. The War Department had told him about its own search for spies at Los Alamos. He began to realize that control of the bomb was not simply a matter of winning the war. It was about national survival after the war was won.

Not long before Pearl Harbor, Hoover and his aides had written about the wartime goals of British intelligence: “

to be in a position at the end of the war to organize the world.” Hoover thought that role rightfully belonged to the United States. The atomic bomb would be the key to its supremacy. And Hoover believed that only the FBI could protect the secrecy and the power of America’s national security.

The final battles of the war still lay ahead. But Hoover had started his struggle for control of American intelligence. He set out to command the course of the Cold War for the government of the United States.

P

ART

III

COLD WAR

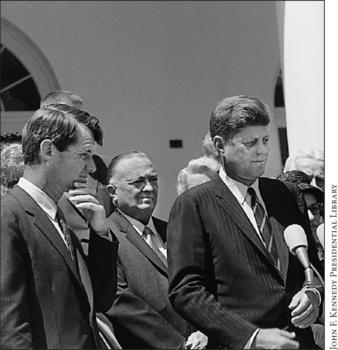

President Kennedy and his brother, the attorney general, struggled to control Hoover’s power over secrets

.

16

NO GESTAPO

I

N THE FIRST

days of February 1945, President Roosevelt lived in the Livadia Palace, the summer home of the last czar of Russia, Nicholas II. The ruined villages of the Yalta Mountains lay around him, covered in snow, ravaged by war.

Roosevelt met Churchill and Stalin at Yalta to chart the course of the world after the war. They all believed, as Churchill said, that “

the right to guide the course of history is the noblest prize of victory.”

Back home, on February 9, the headlines in big-city daily papers owned by FDR’s political archenemies read:

PROJECT FOR U.S. SUPER-SPIES DISCLOSED

…

SUPER GESTAPO AGENCY

…

WOULD TAKE OVER FBI

. There in black and white, word for word, was every inch of Wild Bill’s blueprint for a worldwide intelligence agency. A follow-up story began: “

The joint chiefs of staff have declared war on Brigadier General William J. Donovan.”