Enemies: A History of the FBI (50 page)

Read Enemies: A History of the FBI Online

Authors: Tim Weiner

Ten days later, Hoover fired Bill Sullivan and locked him out of his offices at the FBI—a decision based on his judgment that Sullivan had lost his mind. Even Sullivan’s loyal subordinates were inclined to agree with that assessment. “

He may have suffered a mental collapse,” wrote Ray Wannall, a top FBI intelligence supervisor, who had known Sullivan since 1947, “perhaps brought on by his obsession to become FBI Director.”

On the day he was forced out, Sullivan was struggling in vain to secure his files, including a copy of the poison-pen letter he had sent to Martin Luther King, among other potentially incriminating documents. In the corridor, he ran into the man Hoover had chosen to supplant him: a tall, suave thirty-year veteran of the FBI named Mark Felt, who was searching without success for the copies of the wiretap summaries that Sullivan had stolen. He was convinced that Sullivan had become a renegade, trying to claw his way to power by “

playing on the paranoia and political obsessions of the Nixon administration.”

Felt called Sullivan a Judas. They came close to a fistfight. In a rage, Sullivan left the Bureau for the last time.

Felt went to Hoover’s inner sanctum to brief the director on the altercation. Hoover listened, shook his head sadly, and stared out the window. He had long feared a betrayal from within. “

There were a few men who could tear down all that I have built up over the years,” he had written. Now, for the first time, Felt saw Hoover as he was—an isolated old man, alone at the top, no longer basking in adulation, fearing for the future.

The battle over the FBI intensified. Hoover’s fate was the subject of a ferocious debate in the Oval Office throughout October.

M

ITCHELL:

We have those tapes, logs and so forth over in Mardian’s safe on that background investigation, wiretapping we did on Kissinger’s staff, the newspapermen and so forth …

E

HRLICHMAN:

We have all the FBI’s copies.

M

ITCHELL:

Hoover is tearing the place up over there trying to get at them … Should we get them out of Mardian’s office before Hoover blows the safe? …

E

HRLICHMAN:

Hoover feels very insecure without having his own copy of those things because of course that gives him leverage with Mitchell and with you—and because they’re illegal … He has agents all over this town interrogating people, trying to find out where they are …

P

RESIDENT

N

IXON:

He doesn’t even have his own?

E

HRLICHMAN:

No, see, we’ve got ’em. Sullivan sneaked ’em out to Mardian.

M

ITCHELL:

… Hoover won’t come and talk to me about it. He’s just got his Gestapo all over the place … I want to tell you that I’ve got to get him straightened out, which may lead to a hell of a confrontation … I don’t know how we go about it, whether we reconsider Mr. Hoover and his exit or whether I just have to bear down on him …

P

RESIDENT

N

IXON:

My view is he ought to resign while he’s on top, before he becomes an issue … The least of it is he’s too old.

M

ITCHELL:

He’s getting senile, actually.

P

RESIDENT

N

IXON:

He should get the hell out of there. Now it may be, which I kind of doubt, I don’t know, maybe, maybe I could just call him in and talk him into resigning.

M

ITCHELL:

Shall I go ahead with this confrontation, then?

P

RESIDENT

N

IXON:

If he does go, he’s got to go of his own volition. That’s what we get down to. And that’s why we’re in a hell of a problem … I think he’ll stay until he’s 100 years old. I think he loves it … He loves it.

M

ITCHELL:

He’ll stay ’til he’s buried there.

Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Mitchell, and Dean all pushed the president to force the old man out.

Nixon had come to the most perilous point of his presidency. He could ill afford to lose Hoover’s loyalty. What might the director do to hold on to his power? The hint of blackmail lingered.

“

We’ve got to avoid the situation where he could leave with a blast,” Nixon said. “We may have on our hands here a man who will pull down the temple with him, including me.”

The idea that Hoover could bring down the government of the United States was an extraordinary thought. It plagued the president. “I mean, he considers himself a patriot, but he now sees himself as McCarthy did,” Nixon said. Would he try to topple the pillars of national security, as Senator McCarthy had done?

Then he had a brainstorm. Why not bring back Sullivan?

Ehrlichman liked the idea. “

Sullivan was the man who executed all of your instructions for the secret taps,” he reminded the president.

P

RESIDENT

N

IXON:

Will he rat on us?

E

HRLICHMAN:

It depends on how he’s treated …

P

RESIDENT

N

IXON:

Can we do anything for him? I think we better.

E

HRLICHMAN:

What he wants, of course, is vindication. He’s been bounced, in effect, and what he wants is the right to honorably retire and so on. I think if you did anything for Sullivan, Hoover would be offended. Right now, it would have to be a part of the arrangement …

P

RESIDENT

N

IXON:

He’d be a hell of an operator …

E

HRLICHMAN:

We could use him … He’s got a fund of information and could do all kinds of intelligence and other work.

Nixon would return time and again to the thought of making Sullivan the director of the FBI. “

We got to get a professional in that goddamn place,” he once muttered. “Sullivan’s our guy.”

“I

T WOULD HAVE KILLED HIM

”

An impassioned diatribe from Sullivan arrived at Hoover’s home on the day that the debate over the director’s future started at the White House. It read like a cross between a Dear John letter and a suicide note. “This complete break with you has been a truly agonizing one for me,” he wrote. But he felt duty-bound to say that “the damage you are doing to the Bureau and its work has brought all this on.”

He laid out his accusations in twenty-seven numbered paragraphs, like the counts of a criminal indictment. Some dealt with Hoover’s racial prejudices; the ranks of FBI agents remained 99.4 percent white (and 100 percent male). Some dealt with Hoover’s use of Bureau funds to dress up his home and decorate his life. Some dealt with the damage he had done to American intelligence by cutting off liaisons with the CIA. Some came close to a charge of treason.

“You abolished our main programs designed to identify and neutralize the enemy,” he wrote, referring to COINTELPRO and the FBI’s black-bag jobs on foreign embassies. “You know the high number of illegal agents operating on the east coast alone. As of this week, the week I am leaving the FBI for good, we have not identified

even one of them

. These illegal agents, as you know, are engaged, among other things, in securing the secrets of our defense in the event of a military attack so that our defense will amount to nothing. Mr. Hoover, are you thinking? Are you really capable of thinking this through? Don’t you realize we are betraying our government and people?”

Sullivan struck hardest at Hoover’s cult of personality: “As you know you have become a legend in your lifetime with a surrounding mythology linked to incredible power,” he wrote. “We did all possible to build up your legend. We kept away from anything which would disturb you and kept flowing into your office what you wanted to hear … This was all part of the game but it got to be a deadly game that has accomplished no good. All we did was to help put you out of touch with the real world and this could not help but have a bearing on your decisions as the years went by.” He concluded with a plea: “I gently suggest you retire for your own good, that of the Bureau, the intelligence community, and law enforcement.” Sullivan leaked the gist of his letter to his friends at the White House and a handful of reporters and syndicated columnists. The rumors went out across the

salons and newsrooms of Washington: the palace revolt was rising at the FBI. The scepter was slipping from Hoover’s grasp.

“

As political attacks on him multiplied and became increasingly shrill and unfair,” Mark Felt wrote, “Hoover experienced loneliness and a fear that his life’s work was being destroyed.”

The president slowly pushed Hoover away from the White House. One last hurrah came at the end of 1971: an invitation to Nixon’s compound at Key Biscayne, Florida, over Christmas week, and a cake to celebrate Hoover’s seventy-seventh birthday aboard Air Force One during the return to Washington on New Year’s Eve. But after that, over the next four months the White House logs record only three telephone calls, lasting a total of eight minutes, between Nixon and Hoover. Silence descended.

The last conversation with Hoover that anyone at the FBI recorded for posterity took place on April 6, 1972. Ray Wannall, who had spent thirty years hunting Communists for Hoover, went to the director’s office to receive a promotion. Hoover began a jeremiad, a wail of pain. “

That son of a bitch Sullivan pulled the wool over my eyes,” he said. “He completely fooled me. I treated him like a son and he betrayed me.” His lamentation went on for half an hour. Then he said good-bye.

P

ART

IV

WAR ON TERROR

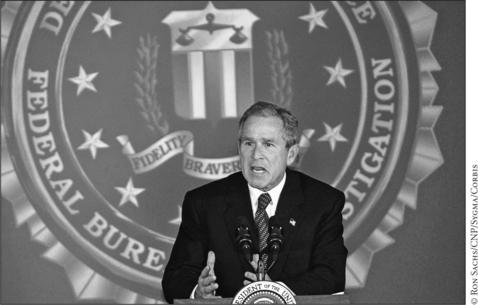

“Round up the evildoers”:

President Bush at FBI headquarters after the 9/11 attacks

.

35

CONSPIRATORS

O

N

M

AY

2, 1972, in the darkness before dawn, J. Edgar Hoover died in his sleep. It rained all day as his closed casket lay on a black catafalque in the rotunda of the United States Capitol. He was buried half a mile from where he was born, alongside his parents. Forty years later, the myths and the legends are still alive.