Equilateral (20 page)

Authors: Ken Kalfus

“This can’t be!” she protests, realizing at once that it can. She searches his face for a sign that he will soften his heart. “The Equilateral is meant to serve humanity—”

“Millions have been raised for the endeavor, Miss Keaton. The investors expect to profit.”

She shudders in response. A tremor pulses through Sir Harry as well: sympathy. He never should have allowed Thayer to keep her in the desert. But the governors were unanimous in their decision to bar Thayer from the commission.

Miss Keaton leaves the customs house without ceremony, a

tiny figure beneath the vastness of Point A’s constructions, within the barren enormousness of the Western Desert, under the immense dish of the ceramic sky. She recognizes now that the purposes of the Concession have been visible all the time.

She doesn’t inform Thayer about the composition of the welcoming commission. He sleeps most of the day anyway, dreaming of a basic language that he may share with his visitors. He murmurs of diameters and ellipses, of octagons and parabolas, of trapezoids and dodecahedrons.

In this glorious culmination of nineteenth-century engineering, organization, and muscle, the customs house is completed—two frenzied weeks into the month of June, but before any sign of the vessels that will arrive from Mars. The Khedive comes with an entourage three times as large as the one that brought him previously. His line of camels sways to the horizon. The viceroy is shortly followed by European prime ministers and heads of state, along with men of industry and ambassadors assigned to relations with Mars. Accommodations consistent with their positions and honors have been constructed for them all. Point A, this formerly anonymous point in the desert, now witnesses the greatest convocation of temporal power since the Congress of Vienna. The newspapers speculate that to ensure political order within the solar system an interplanetary Metternich will have to emerge from the rising city at the Vertex.

The political delegations are shadowed by the many leading astronomers who establish temporary observatories along Point A’s unlit outer perimeter, where they hotly contest each other for the first glints of sunlight dimly reflected off the surfaces

of the Martian vessels. Thayer has calculated that the fleet’s trajectory will pass to the edge of Pisces, perform a slight retrograde pirouette, and then glide through Gemini, Cancer, and Leo for the descent to Earth. The astronomers fix their stare on the loving twins, the scuttling crab, and the imperial lion. The year 1895 will reveal a wealth of asteroids, planetary satellites, double stars, clusters, and nebulae. But every tentative sighting of the travelers from Mars, announced in the night, communicated across Point A’s outskirts by high-stepping runners, welcomed, doubted, and disputed by men who strain against the limits of sight at their own eyepieces, remains unconfirmed.

Miss Keaton tells Thayer of the celestial discoveries. Sometimes the astronomer simply nods, as if he isn’t listening, but on certain days when the fever has subsided and his eyes clear, he demands their details. When the secretary tells him that Professor Hockstader has reported a seventh-magnitude comet in Virgo, Thayer snorts.

“Has he announced its orbital elements?”

Miss Keaton looks at her notes. The comet hunter’s deductions are based on its passage through the constellation over the past three nights. “Mean daily motion, eleven minutes. Perihelion, one-point-five astronomical units. Orbital period, two-point-eight years.”

“Doubtful,” Thayer says, working up a grin. “It can’t be moving that fast. Hockstader’s a good observer, but no mathematician. I wouldn’t trust him to make change from a pound note.”

“The numbers haven’t been verified.”

“They won’t be,” he declares.

Thayer is quiet for a few minutes, his forehead creased. He isn’t falling asleep.

He says at last, “I bet they’re getting impatient.”

“Who?”

“About the Martian vessels. They haven’t seen them yet, have they? They’re looking in Leo’s every nook and cranny. No ships?”

Miss Keaton doesn’t respond. She has refrained from reporting the astronomers’ increasing uneasiness, which is joined by an even greater restlessness among the statesmen and Concession governors who have come to Point A. The European newspapers are publishing leaders with headings like WHERE ARE THEY?

“They

can’t

see them!”

“Professor Verzola has been assembling his eleven-inch refractor. He says he’ll be ready to observe this evening.”

“I’ve performed new calculations. In my head.”

His cheeks and temples are flushed now and he’s speaking in a hoarse shout. His stare is not directly at her.

“You have to rest, Pho. There’s no need to calculate in your head,” she says. She adds, after taking a moment to clear something stuck in her throat, “I’m here, you know.”

“The ships from Mars won’t be any brighter than the twelfth magnitude until they’re almost upon us. None of these instruments, not even Verzola’s, will pick them up, certainly not with his vision. The man needs glasses. Twelfth magnitude, Dee!”

“All right, I’ll tell them.”

“And they won’t show up on any plates either. They shouldn’t waste their film.”

Δ

As the days pass in unremitting sun, the statesmen of Europe meet to exchange views on terrestrial concerns, especially unrest in the Transvaal and loans to China. Certain levers of power are softly pressed. Borders in the Balkans are quietly redrawn. Populations are shifted. Sums are debited and credited to the accounts of distant banks. A royal engagement is arranged; so is an assassination.

Although Ballard’s work at Point A is largely done, the momentum of the rush toward completion still runs through him. He finds calm only when he’s with Thayer in the astronomer’s darkened room, sitting by his bed, smoking, usually when Miss Keaton is elsewhere engaged. Their conversation is desultory, broken by lengthy, dream-soaked pauses, and the two men occasionally revisit the delays in the excavations, for Thayer doesn’t recall, from time to time, that the Equilateral was finished last year.

Thayer doesn’t inquire about the Arab girl in the next room. She has entered her confinement in some discomfort or pain that the sisters fail to identify or alleviate. They’re not a little put out when Miss Keaton, alarmed by her fever, sends for a Bedouin midwife.

The astronomer ceases to speak of the Equilateral, or of his colleagues camped around Point A, or of the planet Mars. Whether or not Ballard or Miss Keaton are with him, his murmurings now roam into space’s deepest reaches, often in the

direction of the objects he observed from Chile on the 1890 expedition. “It’s a pinwheel of gas, three distinct wings, so luminous you may turn them with a sigh. Messier 83, at the edge of the Centaur. A fresh pencil, please … The Magellanic Clouds, great nurseries of stars cottoned in a primeval gaseous haze. This is proof, proof positive of the hypothesis that the nebulae coalesce …”

On his rounds Ballard ensures that everything he has constructed at Point A—the gasworks, the waterworks, the sewage system—is operating correctly. He inspects the wide processional boulevard, which begins, its stones washed twice a day, at the customs house and terminates at the palace for the visiting heads of state. The palace is modeled on Balmoral. Drawing from the designs of recent constructions like the Reichstag and the Hôtel de Ville, lesser diplomatic and commercial buildings line the road. Ballard searches between and beyond them, into the alkali desolation, for one more thing to build. He avoids the Concession offices, where men from London have come. They’re in their offices, writing and reading reports, but they have little to do until the Martian embassy arrives. Among the diplomats he senses a rising tension. They look into his face with questions; when they step outside, they can’t help but lift their heads to the vacant sky.

Three weeks after the day in which the ships were expected to land, the mood shifts decisively. Ballard senses that the impatience rippling beneath the sands of the encampment has curdled into anger. Sir Harry goes quiet, as if his face has been slapped. Perhaps it has been, by one of the other governors or an investor or a member of Parliament. The dignitaries talk of

departing Point A, for they have nations and empires to run. There’s only so much time that the prime minister of Britain can spend with the president of France before troubles arise somewhere in Africa. The leaders will allow their envoys, or their junior envoys, to attend the travelers, if they come at all. Yet none hurries to leave, fearful of yielding a diplomatic advantage.

The Khedive and his Egyptian retinue have installed themselves in a wing of the palace, in disregard of common diplomatic protocol. On the one hand the Khedive appears to imagine that social intercourse with Egypt will be Mars’ primary objective; at the same time he urges his fellow dignitaries to remain at Point A to demonstrate mankind’s solidarity. “The visitors from Mars will care little to distinguish either between the Frenchman and the German or the Egyptian and the Englishman,” he says, raising hackles up and down the palace’s plushly carpeted, electrically lit corridors.

Ballard observes that neither the political leaders nor the Concession’s governors require further construction. They’re beginning to look for men to blame, and with Thayer absent, the engineer is the most conspicuous of them.

Δ

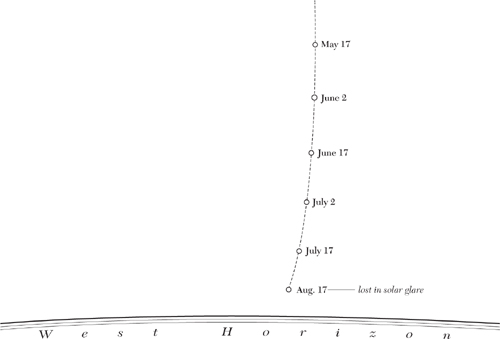

Every day the Red Planet sets earlier and a few degrees closer to the sun, which has blazed the path ahead of it into Leo. As seen from Mars, the Earth appears to sink every morning farther into the dawn. On the evening of August 16, 1895, shortly after the onset of dusk, Professor Verzola makes out the last of Mars. He says that by the following evening it will not be viewable at all. This declaration of heliacal descension, long foreseen in ephemeridic columns and tables, rumbles through the city. At daybreak, as blown sand starts to obscure the Equilateral, the British prime minister and the French president depart for Alexandria in separate caravans. Ballard understands that Sir Harry is in a rage.

Mars as seen from Earth, 1895, end of evening twilight.

That afternoon, with Mars conclusively hidden by the solar glare, Ballard climbs to the third floor of the infirmary. He recognizes that something is wrong before he reaches the landing. A low, grinding, worried murmur spills down the stairs. When he arrives he’s confronted by two French nurses outside the open door to the girl’s room, scowling.

The engineer represses his natural squeamishness and looks in. The small whitewashed room has been occupied by a contingent of robed Bedouin women, their faces hidden. They surround the hospital bed. Ballard can’t see the girl. One of the women must be the midwife. He presumes the others are from her family and clan. He detects the scent of raw garlic; also of fenugreek and cardamom.

He goes to Thayer’s room.

“Sanford!” he says heartily. “How are you feeling, old man? We’ve got a bit of a wind up today.”

He drops himself into a chair next to Miss Keaton, before realizing that he’s intruded. They ignore him, or they haven’t noticed his entrance. But the attending sister flares to Ballard an expression of grave significance.

Thayer’s no longer speaking with Miss Keaton about nebulae. Sweat illumines his face and his eyes are as vivacious as a

schoolboy’s. He’s telling her, “It was a full day’s journey from San Pedro, Dee.”

“That’s right,” she says. “About nine hours.”

“You rode the frisky bay. The boys made camp on an elevated ridge protected by a stand of mesquite trees. They prepared dinner over the campfire, a chupe stew, fresh beefsteak and rice and red beans, served with a peppery sauce and a cactus salad. Dusk came. We set up the refractor, established polar alignment. There was good-to-excellent seeing. I ranked it a nine on the Douglass Scale. We made our observations, the southern nebulae, the Messiers. When we returned to the fire for warmth, the boys had faded into the distant shadows. We couldn’t hear them, save for the occasional melancholy airs of a mouth organ. We were left to ourselves. We couldn’t see the stars, the campfire was too intense. We saw only each other. Whatever lies beyond the fire is …” Thayer falls silent for several moments. Then he completes the thought: “Unknown.”

Ballard doesn’t move, not even to exhale. He can’t withdraw from the sickroom for fear of drawing attention to himself.

“There’s only us,” Miss Keaton affirms, whispering.

“Only us,” Thayer repeats, closing his eyes for a moment. But still he speaks. “Only the two of us, two minds … We’ve understood each other from the start. We need each other. It’s irrefutable.”

He opens his eyes. Ballard realizes, with a start, that Thayer can’t see at all, yet his eyes remain fixed on Miss Keaton.

Thayer shudders. He’s silent for a few minutes before he continues: “Flame light kisses your face, which is completely, boldly

open to my gaze. I ask a question, without words, but a gesture, comprising a quarter smile and my direct look, becomes comprehensible by the miracle of concordant intellects. You smile as I’ve never seen you smile before. I understand your sign in return, which speaks of agreement, and also of trust and kindness. It speaks too of appetite. All that in a smile! We retire to my tent without a word. Our embrace is gentle, but hardly tentative. We fumble with fasteners, but nothing proves awkward, ever.”