Errantry: Strange Stories

Read Errantry: Strange Stories Online

Authors: Elizabeth Hand

Table of Contents

errantry

strange

stories

elizabeth

hand

Small Beer Press

Easthampton, MA

This is a work of fiction. All characters and events portrayed

in this book are either fictitious or used fictitiously.

Errantry: Strange Stories

copyright

©

2012 by Elizabeth Hand (elizabethhand.com). All rights reserved. Page 291 of the print version functions as an extenstion of the copyright page.

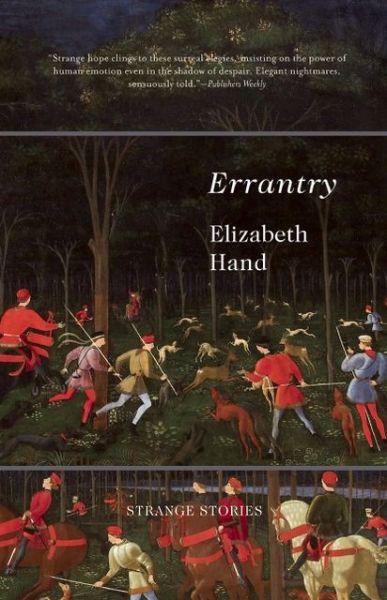

Cover image “The Hunt in the Forest” by Paolo Uccello by permission of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford (ashmolean.org).

Small Beer Press

150 Pleasant Street #306

Easthampton, MA 01027

www.smallbeerpress.com

www.weightlessbooks.com

Distributed to the trade by Consortium.

First Edition 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hand, Elizabeth.

Errantry : strange stories / Elizabeth Hand. -- 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-61873-030-5 (alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-61873-031-2 (ebook)

I. Title.

PS3558.A4619E77 2012

813’.54--dc23

2012035129

Text set in Minion.

Paper edition printed on 50# Natures Natural 30% PCR Recycled Paper by C-M Books in Ann Arbor, MI.

DRM-free ebook available from smallbeerpress.com.

For Rafael Sa’adah,

Trusted guide in Bellona, and beyond

With all my love and thanks

The Maiden Flight of McCauley’s

Bellerophon

Being assigned to The Head for eight hours was the worst security shift you could pull at the museum. Even now, thirty years later, Robbie had dreams in which he wandered from the Early Flight gallery to Balloons & Airships to Cosmic Soup, where he once again found himself alone in the dark, staring into the bland gaze of the famous scientist as he intoned his endless lecture about the nature of the universe.

“Remember when we thought nothing could be worse than that?” Robbie stared wistfully into his empty glass, then signaled the waiter for another bourbon and Coke. Across the table, his old friend Emery sipped a beer.

“I liked The Head,” said Emery. He cleared his throat and began to recite in the same portentous tone the famous scientist had employed. “Trillions and trillions of galaxies in which our own is but a mote of cosmic dust. It made you think.”

“It made you think about killing yourself,” said Robbie. “Do you want to know how many time I heard that?”

“A trillion?”

“Five thousand.” The waiter handed Robbie a drink, his fourth. “Twenty-five times an hour, times eight hours a day, times five days a week, times five months.”

“Five thousand, that’s not so much. Especially when you think of all those trillions of galleries. I mean galaxies. Only five months? I thought you worked there longer.”

“Just that summer. It only seemed like forever.”

Emery knocked back his beer. “A long time ago, in a gallery far, far away,” he intoned, not for the first time.

Thirty years before, the Museum of American Aviation and Aerospace had just opened. Robbie was nineteen that summer, a recent dropout from the University of Maryland, living in a group house in Mount Rainier. Employment opportunities were scarce; making $3.40 an hour as a security aide at the Smithsonian’s newest museum seemed preferable to bagging groceries at Giant Food. Every morning he’d punch his time card in the guards’ locker room and change into his uniform. Then he’d duck outside to smoke a joint before trudging downstairs for morning meeting and that day’s assignments.

Most of the security guards were older than Robbie, with backgrounds in the military and an eye on future careers with the D.C. Police Department or FBI. Still, they tolerated him with mostly good-natured ribbing about his longish hair and bloodshot eyes. All except for Hedge, the security chief. He was an enormous man with a shaved head who sat, knitting, behind a bank of closed-circuit video monitors, observing tourists and guards with an expression of amused contempt.

“What are you making?” Robbie once asked. Hedge raised his hands to display an intricately patterned baby blanket. “Hey, that’s cool. Where’d you learn to knit?”

“Prison.” Hedge’s eyes narrowed. “You stoned again, Opie? That’s it. Gallery Seven. Relieve Jones.”

Robbie’s skin went cold, then hot with relief when he realized Hedge wasn’t going to fire him. “Seven? Uh, yeah, sure, sure. For how long?”

“Forever,” said Hedge.

“Oh, man, you got The Head.” Jones clapped his hands gleefully when Robbie arrived. “Better watch your ass, kids’ll throw shit at you,” he said, and sauntered off.

Two projectors at opposite ends of the dark room beamed twin shafts of silvery light onto a head-shaped Styrofoam form. Robbie could never figure out if they’d filmed the famous scientist just once, or if they’d gone to the trouble to shoot him from two different angles.

However they’d done it, the sight of the disembodied Head was surprisingly effective: it looked like a hologram floating amid the hundreds of back-projected twinkly stars that covered the walls and ceiling. The creep factor was intensified by the stilted, slightly puzzled manner in which The Head blinked as it droned on, as though the famous scientist had just realized his body was gone, and was hoping no one else would notice. Once, when he was really stoned, Robbie swore that The Head deviated from its script.

“What’d it say?” asked Emery. At the time, he was working in the General Aviation Gallery, operating a flight simulator that tourists clambered into for three-minute rides.

“Something about peaches,” said Robbie. “I couldn’t understand, it sort of mumbled.”

Every morning, Robbie stood outside the entrance to Cosmic Soup and watched as tourists streamed through the main entrance and into the Hall of Flight. Overhead, legendary aircraft hung from the ceiling. The 1903

Wright Flyer

with its Orville mannequin; a Lilienthal glider; the Bell X-1 in which Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier. From a huge pit in the center of the Hall rose a Minuteman III ICBM, rust-colored stains still visible where a protester had tossed a bucket of pig’s blood on it a few months earlier. Directly above the entrance to Robbie’s gallery dangled the

Spirit of St. Louis.

The aides who worked upstairs in the planetarium amused themselves by shooting paperclips onto its wings.

Robbie winced at the memory. He gulped what was left of his bourbon and sighed. “That was a long time ago.”

“Tempus fugit, baby. Thinking of which—” Emery dug into his pocket for a Blackberry. “Check this out. From Leonard.”

Robbie rubbed his eyes blearily, then read.

From:

[email protected]

Subject: Tragic Illness

Date:

April 6, 7:58:22 PM EDT

Dear Emery,

I just learned that our Maggie Blevin is very ill. I wrote her at Christmas but never heard back. Fuad El-Hajj says she was diagnosed with advanced breast cancer last fall. Prognosis is not good. She is still in the Fayetteville area, and I gather is in a hospice. I want to make a visit though not sure how that will go over. I have something I want to give her but need to talk to you about it.

L.

“Ahhh.” Robbie sighed. “God, that’s terrible.”

“Yeah. I’m sorry. But I figured you’d want to know.”

Robbie pinched the bridge of his nose. Four years earlier, his wife, Anna, had died of breast cancer, leaving him adrift in a grief so profound it was as though he’d been poisoned, as though his veins had been pumped with the same chemicals that had failed to save her. Anna had been an oncology nurse, a fact that at first afforded some meager black humor, but in the end deprived them of even the faintest of false hopes borne of denial or faith in alternative therapies.

There was no time for any of that. Zach, their son, had just turned twelve. Between his own grief and Zach’s subsequent acting-out, Robbie got so depressed that he started pouring his first bourbon and Coke before the boy left for school. Two years later, he got fired from his job with the County Parks Commission.

He now worked in the shipping department at Small’s, an off-price store in a desolate shopping mall that resembled the ruins of a regional airport. Robbie found it oddly consoling. It reminded him of the museum. The same generic atriums and industrial carpeting; the same bleak sunlight filtered through clouded glass; the same vacant-faced people trudging from Dollar Store to SunGlass Hut, the way they’d wandered from the General Aviation Gallery to Cosmic Soup.

“Poor Maggie.” Robbie returned the Blackberry. “I haven’t thought of her in years.”

“I’m going to see Leonard.”

“When? Maybe I’ll go with you.”

“Now.” Emery shoved a twenty under his beer bottle and stood. “You’re coming with me.”

“What?”

“You can’t drive—you’re snackered. Get popped again, you lose your license.”

“Popped? Who’s getting popped? And I’m not snackered, I’m—” Robbie thought. “Snockered. You pronounced it wrong.”

“Whatever.” Emery grabbed Robbie’s shoulder and pushed him to the door. “Let’s go.”

Emery drove an expensive hybrid that could get from Rockville to Utica, New York, on a single tank of gas. The vanity plate read MARVO and was flanked by bumper stickers with messages like GUNS DON’T KILL PEOPLE: TYPE 2 PHASERS KILL PEOPLE and FRAK OFF! as well as several slogans that Emery said were in Klingon.

Emery was the only person Robbie knew who was somewhat famous. Back in the early 1980s, he’d created a local-access cable TV show called Captain Marvo’s Secret Spacetime, taped in his parents’ basement and featuring Emery in an aluminum foil-costume behind the console of a cardboard spaceship. Captain Marvo watched videotaped episodes of low-budget 1950s science fiction serials with titles like PAYLOAD: MOONDUST while bantering with his co-pilot, a homemade puppet made by Leonard, named Mungbean.

The show was pretty funny if you were stoned. Captain Marvo became a cult hit, and then a real hit when a major network picked it up as a late-night offering. Emery quit his day job at the museum and rented studio time in Baltimore. He sold the rights after a few years, and was immediately replaced by a flashy actor in Lurex and a glittering robot sidekick. The show limped along for a season then died. Emery’s fans claimed this was because their slacker hero had been sidelined.

But maybe it was just that people weren’t as stoned as they used to be. These days the program had a surprising afterlife on the internet, where Robbie’s son, Zach, watched it with his friends, and Emery did a brisk business selling memorabilia through his official Captain Marvo website.

It took them nearly an hour to get into D.C. and find a parking space near the Mall, by which time Robbie had sobered up enough to wish he’d stayed at the bar.

“Here.” Emery gave him a sugarless breath mint, then plucked at the collar of Robbie’s shirt, acid-green with SMALLS embroidered in purple. “Christ, Robbie, you’re a freaking mess.”

He reached into the backseat, retrieved a black T-shirt from his gym bag. “Here, put this on.”

Robbie changed into it and stumbled out onto the sidewalk. It was mid-April but already steamy; the air shimmered above the pavement and smelled sweetly of apple blossom and coolant from innumerable air conditioners. Only as he approached the museum entrance and caught his reflection in a glass wall did Robbie see that his T-shirt was emblazoned with Emery’s youthful face and foil helmet above the words O CAPTAIN MY CAPTAIN.