Escape from Alcatraz (33 page)

Read Escape from Alcatraz Online

Authors: J. Campbell Bruce

During the Sioux stay two men (white) planted a marker on the shore, then filed a placer mining claim to the island, calling it the Embarrassing Mine. The Sioux said: “Let them remember General Custer.” They remembered. But they had a day of limelight, for only $2.80, the filing fee.

The second invasion was in greater force (several hundred braves); of longer duration (a year and a half), and far more successful: it focused national attention on the plight of the Indian, who did hold rightful claim to the title of American Original. The GSA let time and hardship handle the situation. The Indians left a year later. They did spare the government the expense of wrecking many of the buildings, but some felt they might have spared the warden’s big house on the cliff’s edge across the road from the prison. A spectacular midnight blaze left it a charred shell, and destroyed the nearby living quarters of the Coast Guard lightkeepers. (An automatic light was later installed.)

Closing the problem island created a new problem: what to do with it? In the American bureaucratic tradition, studies were launched, even a $20,000 one to fix its worth. (Its worth: $2,178,000—$178,000 for the twelve acres, $2 million for the buildings. This was in 1964, when the place was still intact.) A President’s Alcatraz Study Commission called for suggestions, and was almost blown away by the hurricane. Just about every use conceivable (and inconceivable) was proposed, except the one thing it finally became: part of a park.

Among the more notable proposals: a Statue of Liberty West; an anchor for a bridge to the north; a pleasure park after Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens; a gambling casino; a cathedral; a college; an observatory; a round Parthenon, fifty feet high, with shops and restaurants in a wing-like roof; a refuge for seagulls (from the school children of Bird City, Kansas, pop. 678); a Sin City (no minors ashore); give it back to the pelicans (the pelicans weren’t interested); a “nudist metropolis”; let tourists be “a convict for a day,” for a fee (a Walt Disney thought); a 364-foot tower, Apollon, honoring the space program; an 800-foot parabolic arch of stainless steel, honoring the peoples of the world; a great globe of the world, 250 feet in diameter, circled by an olive wreath and resting on a pedestal of highrise buildings (by Buckminster Fuller of the geodesic dome); a vast hotel shaped like a horseshoe; a vaster hotel and convention center accommodating 12,000 people; a shopping center. And the inevitable wag: “I think it’d make a good federal prison.”

The Commission recommended a monument to commemorate the founding of the United Nations in San Francisco, which would serve “untold generations as an ennobling inspiration …” (They would raze the prison, though not as one person proposed; gradually, by the falling water of a jet roaring 500 feet above the fog.)

The studies, in the American bureaucratic tradition, went into the archives. Left to brood in its summer fogs, this isle of infamy, this American Devil’s Island held ever greater fascination for sightseers, feeding dimes into binoculars at Fisherman’s Wharf and up on Telegraph Hill. Then, last year, Congress created the 36,000-acre Golden Gate National Recreation Area—its smallest playground.

When Alcatraz was a pet project of the Department of Justice, people were threatened with machine-gun fire if they came too near. Now the National Park Service is in charge, and they can take a walking tour of the island, then a gawking tour of the silent cellhouse—even step into a cell of the Dark Hole, pull the steel door shut, and feel the skin prickle in the blackness.

J.C.B.

Berkeley

September 1973

View of Alcatraz from North Point, 1865.

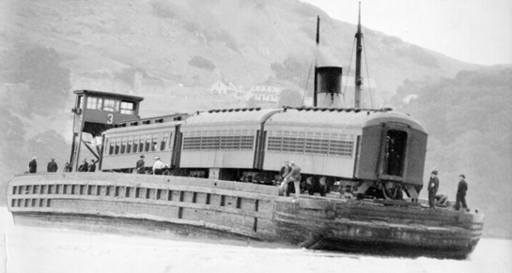

Alcatraz Island prison train en route from Tiburon, 1934.

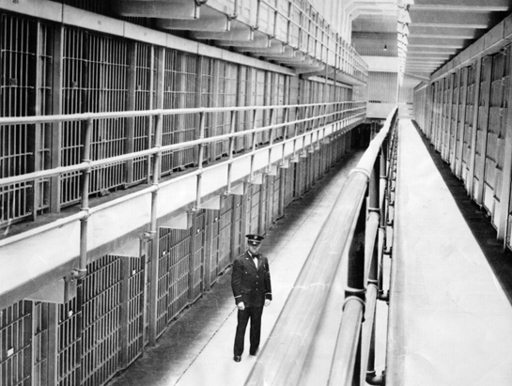

Three tiers of the Alcatraz main cell block, 1934.

Alcatraz inmate George “Machine Gun” Kelly, 1933.

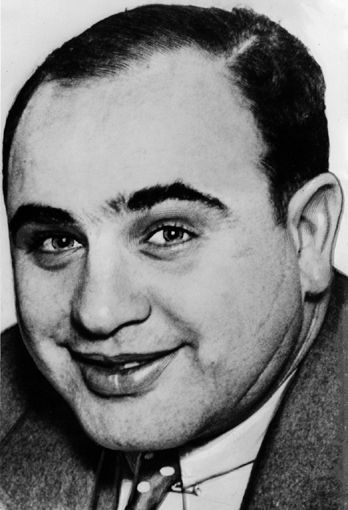

Chicago crime boss Al “Scarface” Capone, who spent four and a half years in Alcatraz, 1936

Convicts James Lucas and Rufus Franklin, who failed in their escape attempt from Alcatraz, 1938.

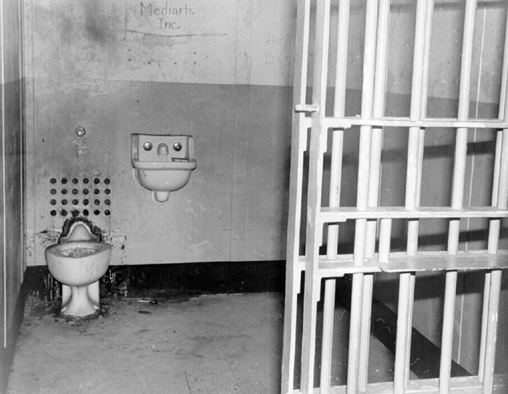

Interior of prison cell, 1941.

Solitary confinement prison cell, 1946.

Rifle grenade bursting in Alcatraz cell block during a three-day prisoner revolt in May 1946.

Alcatraz prison recreation yard, 1956.