Essence and Alchemy

Read Essence and Alchemy Online

Authors: Mandy Aftel

For Becky

Table of Contents

One finds an ancient flask, and from its spout

A spirit, now restored and much alive, pours out

.

A thousand slumbering thoughts, dismal chrysalids

Within the shadows trembling like new butterflies,

Which set themselves to fly, as crumpled wings unfold

In tints of azure, frosts of rose, and flakes of gold

.

A spirit, now restored and much alive, pours out

.

A thousand slumbering thoughts, dismal chrysalids

Within the shadows trembling like new butterflies,

Which set themselves to fly, as crumpled wings unfold

In tints of azure, frosts of rose, and flakes of gold

.

â

Charles Baudelaire, “The Flask”

Charles Baudelaire, “The Flask”

1

1P

ERFUMEâthe heady and elusive marriage of the essences of herbs and spices, wild grasses and flowers, bark and animal and treeâis an engine of the universe. From earliest times, people have taken pleasure in rubbing fragrant substances into their skin. Timeless and universal, scent has been a powerful force in ritual, medicine, myth, and conquest. Perfume has helped people to pray, to heal, to make love and war, to prepare for death, to create. To inspire, after all, is literally “to breathe in.”

Aromatics were highly prized articles of luxury and refinement in the ancient world, and trade routes developed in part around the relentless pursuit of perfume ingredients. From remote civilizations, caravans and ships brought cinnamon from Africa; spikenard and cardamom from India; ginger, nutmeg, saffron, and cloves from Indonesia. Too precious to eat, these materials were coveted components

of the fragrant mixtures used in religious rituals, as physical remedies, and to scent the body. It has been said, with some justice, that the world was discovered in perfume's wake.

of the fragrant mixtures used in religious rituals, as physical remedies, and to scent the body. It has been said, with some justice, that the world was discovered in perfume's wake.

Perfume was not just a product, but a way of being in the world that for centuries retained an aura of magic and mystery. An exclusive but idiosyncratic fraternity, largely self-taught, perfumers were the practical and philosophical heirs to the traditions of alchemy, which had as its aim the transformation of physical matter into divine essence. They kept their formulas a secret and proffered their potions in magnificent flasks to a select few, for great sums of money. As the rise in world trade and the development of distillation and other techniques (some of them originated by the alchemists themselves) made an ever-wider variety of high-quality essences available, perfumers were spurred to new levels of creativity. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the technique known as

enfleurage

bestowed upon them the essences of jasmine, orange blossom, and tuberose, bringing the art of perfumery to full flower.

enfleurage

bestowed upon them the essences of jasmine, orange blossom, and tuberose, bringing the art of perfumery to full flower.

Colorful, unstable, quirky, and expensive, natural essences were a difficult mistress who demanded rapt attention and a willingness to abandon the rules. They never offered the ease of a predictable relationship, and their complexity inspired many of those who worked with them to think philosophically about the relationship of perfume to other aspects of life. The literature that grew up around perfumery, especially in its golden age at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, reveals a world of eccentric artisans who were passionate about scent, intoxicated with the romance of faraway places, and drawn to the bonds of their craft with ancient and mystical traditions.

Those bonds were soon shattered. In 1905, as legend has it, François Coty catapulted his fledgling fragrance business into the world by dropping a bottle of his perfume on the floor of an exclusive department store that had just declined to carry it. Lured by the commotion and the scent he had released, customers rushed over and bought his supply. Legend or no, it was certainly Coty who had the bright idea to package fragrance in small bottles. More crucially, he was among the first perfumers to use synthetics along with natural essences, the decisive factor in making perfume an affordable luxury for the masses.

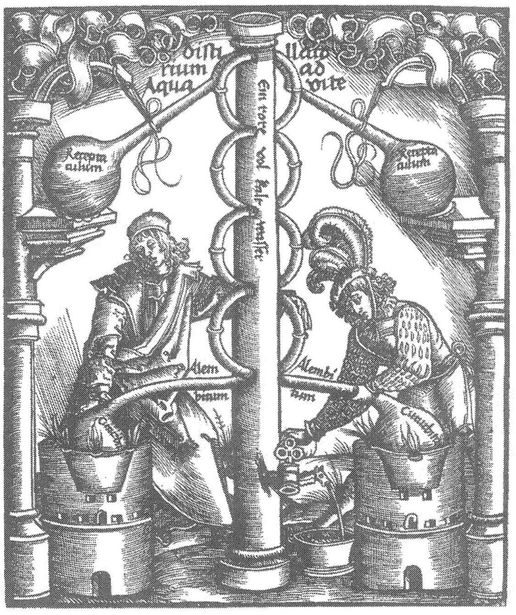

Distillation, from the Destillirbücher by Hieronymus Brunschwig, early sixteenth century

Because of their low price and stability, the synthetics were vigorously promoted and soon replaced natural essences in the manufacture of perfume, except for the precious florals, which were difficult to replicate. Synthetics offered all the reliabilityâand uniformityâof Wonder bread, and being “modern” added to their cachet. They brought about the rise of perfume as a major industry producing brand-name products, and its rapid decline as a craft practiced by artisans. Perfumers still followed the stages of the alchemical processâseparation, purification, recombination, and fixationâbut perfume-making had moved out of the atelier and into the laboratory, both literally and philosophically. And so it happened that a process once as poetic as its result went into eclipse.

A century later, our olfactory sensibility has been marginalized and deadened by the chemicalization of our food and our environment, and the overwhelming proliferation of unnatural smells. The world of natural odors has been co-opted by products; many people cannot smell a lemon without thinking of furniture cleaner. Oversaturation with chemical smells has compromised our ability to appreciate complex and subtle natural odors. Many of my clients have been astonished by a whiff from a vial of rose or jasmine absolute; they have forgottenâor never knewâwhat real flowers smell like. We are bombarded by department-store perfumes that shout their presence and linger monotonously and pervasively on the body and in the air, but the true magic of perfume eludes us. We have lost touch with what drew our kind to the smell of flowers and herbs in the first place, and with the rich and tangled history of our species

and theirs. As Paolo Rovesti writes, in chronicling the lost world of perfumes, “We who are immersed

2

in the unnaturalness of modern-day life cannot recall, without nostalgia and sadness, those gifts of nature at man's disposal, now neglected or in disuse. Among those are the lost paradises of natural perfumes, of the perfumes of the past and of the spirit.”

and theirs. As Paolo Rovesti writes, in chronicling the lost world of perfumes, “We who are immersed

2

in the unnaturalness of modern-day life cannot recall, without nostalgia and sadness, those gifts of nature at man's disposal, now neglected or in disuse. Among those are the lost paradises of natural perfumes, of the perfumes of the past and of the spirit.”

Â

Â

E

ven before I became a perfumer, I loved to work with my hands and to be surrounded by objects made by hand, bearing the peculiar stamp of the maker's sensibility. I was a textile artist in my twenties, and have long been an avid collector of ethnic crafts. I love to garden for scent with flowers and herbs, and I take great pleasure in filling my house with the fragrances of plants I have tended. And while I have created all-natural perfumes for limited large-scale production, my true passion is creating one-of-a-kind perfumes with gorgeous ingredients.

ven before I became a perfumer, I loved to work with my hands and to be surrounded by objects made by hand, bearing the peculiar stamp of the maker's sensibility. I was a textile artist in my twenties, and have long been an avid collector of ethnic crafts. I love to garden for scent with flowers and herbs, and I take great pleasure in filling my house with the fragrances of plants I have tended. And while I have created all-natural perfumes for limited large-scale production, my true passion is creating one-of-a-kind perfumes with gorgeous ingredients.

From the beginning, I loved working with the pure essences. They were voluptuousness in a bottle, and I was elated just by smelling them, as if I were inhaling worlds of experience along with the scents themselves. Some of their names were familiar from reading or cooking or gardening, others absolutely foreign. I began to read about them all, first in the aromatherapy literature, then following the trail laid down in the bibliographies.

I began to seek out antique perfume books at rare-book fairs and from dealers. Over the years I built a library of more than two hundred rare books on scent. Like the essences themselves, they have a complex and eccentric character. Some are filled with fascinating old photographs or woodcuts, others with arcane details about the procurement or use of this oil or that. The authors are wild hares full of opinions and quirksâEugene Rimmel, for example, who was as much a frustrated hairdresser as a perfumer and who, in his elaborately illustrated

Book of Perfumes

, published in 1865, tours the ancient civilizations and the “uncivilized nations,” surveying exotic hairdos and customs of perfumery in almost equal measure. Scholarly or self-taught, earthy or cerebral, these writers share a reverence for natural ingredients and a deep and abiding belief in the importance of scented experience.

Book of Perfumes

, published in 1865, tours the ancient civilizations and the “uncivilized nations,” surveying exotic hairdos and customs of perfumery in almost equal measure. Scholarly or self-taught, earthy or cerebral, these writers share a reverence for natural ingredients and a deep and abiding belief in the importance of scented experience.

Herb garden and distillery, 1516

My reading often suggested a new oil to experiment with or a way of combining ingredients that I hadn't thought of. Sometimes just understanding the history of an essence through civilization after civilization brought it to life in my hands. In these ways, discovering the art of natural perfumery was like crossing the threshold of a beautiful old house and finding it utterly intact and splendidly furnished but deserted, as if it had been suddenly abandoned and was waiting to be reclaimed. I felt privileged to have the opportunity to create with these precious essences, and I began to see myself as a custodian of a sacred and vanishing art.

It is an auspicious moment to step into that role. The popularity of aromatherapy has introduced a new generation to natural essences of excellent quality and has made these materials widely available for purchase. And although existing perfume schools concentrate on synthetic ingredients, natural perfumery is uniquely suited for home study. All that is needed to unlock that beautiful, fragrant house are a basic understanding of methodology, and an appreciation of the history and spirit of the essences themselves.

The study and practice of perfumery is uniquely apt to satisfy the hunger for authenticity that seems more keen in us now than ever. A spiritual process as well as an aesthetic one, the art of perfumery is at once holy and carnal, spiritual and material, arcane and modern, tangible and intangible, profound and superficial. To take part in it is to touch its most ancient roots, especially the long and secretive traditions of alchemy. Alchemy embodied such dualities, as the psychologist Carl Jung recognized in embracing the alchemical process

as a metaphor for the growth of the human soul through conflict, crisis, and change.

as a metaphor for the growth of the human soul through conflict, crisis, and change.

Scent has always provided a direct path to the soul, and no one who becomes immersed in it can fail to be pleasurably changed by the experience. Your curiosity may inspire you to sample a few essences, or perhaps to master a few simple blends that you can use in meditation or in the bath. Or you may decide to throw yourself into the world of essences and the almost narcotic pleasures of working and playing and creating with them. But even if you venture only so far as to read about natural perfume, you are in for an astonishing journey into the grand and exotic past and the hidden, sensual present. To be immersed in a scent world, even temporarily, is to shift your consciousness and to awaken to the moment more fully.

Other books

Love's a Witch by Roxy Mews

B006DTZ3FY EBOK by Farr, Diane

The Fallen 03 - Warrior by Kristina Douglas

Havoc-on-Hudson by Bernice Gottlieb

Borkmann's Point by Håkan Nesser

Visions of Gerard by Jack Kerouac

Eat, Drink and Be Wary by Tamar Myers

The Black Cauldron by Alexander, Lloyd

Gratitude by Joseph Kertes

Lamplighter by D. M. Cornish