Evacuee Boys (10 page)

Authors: John E. Forbat

So please, as soon as you can in your next letter, send us something if only 1/-, because I owe Mrs. Kelly 3

d

for a broken plate, & Mr. Kelly 3

d

for a pump-connector.

By the way, I did receive the parcel.

Please send the money for going home soon, because I want to book my seat a week in advance (14/-).

My trousers look more like a piece of rag, because it is in pieces (more or less) so please send Uncle Eugene’s old trousers, & John’s watch, cub hat & Jersey, because he wants to give it to Mrs. Robbins (most likely she will give John a few shillings for it).

With lots of love,

Andrew (& John)

P.S. John cannot write, his right arm being in plaster. And DON’T worry !!!!!!!!!!! A.

![]()

6

September

1940

Dear Mum & Dad,

I have not had any letter from you since Friday, & I should like you to write more often, especially as there are a lot of air-raids in London & in view of the numerous casualties, it causes me some anxiety with regard to your safety if I have no information for a considerable period of time.

My work is increasing daily, as there are only 11 more weeks to go before the exam & I have to do a great deal of revision & new work in order to get through. The fee is 35/-, & we were told to-day to get it ready, because the applications for the entry will soon have to be sent in.

In spite of the fact that I had 4/6 wages on Saturday, I have only a few coppers left, as John spent 1/1 at Weston (out of his watch money), & I had to pay Mrs. Kelly 1/3 for doing the laundry (saving of 1/6 on the laundry price) & I also bought a 6½

d

box of chocolates for her birthday. Apart from that I bought 4 periodicals, haircream, pencil sharpener, rubbers, notebook & a small amount of sweets. It is terrible how quickly money goes, & I should be obliged if you could send some more.

John says that he needs some socks badly, as Mrs. Robbins is complaining about the enormous holes & the thinness of the socks. Can you send him about 3 pairs!

Just to answer you that there are no air-raids & then to close my letter, because I have lots of work to do to-night yet.

Lots of love from

Andrew

![]()

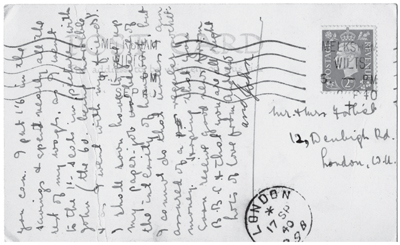

15

September

1940

– a postcard

Dear Mum & Dad,

Sorry I am late in replying to your card (dated the 9th, received the 12th) but as you might guess I am very busy lately.

Please try to write to me as often as you can, & write details about the raids because from what I hear from Billy Childs, who is here for the weed-end, quite a number of bombs were dropped in his district which is not far from ours.

John had the plaster taken off & his arm is still a little stiff. It is very quiet down here so do not worry.

Please send me money if you can. I put 1/6 in the savings & spent nearly all the rest of my wages, as I went to the 1/- seats in pictures with John (the 6

d

being horrible & as I went with my friends). I shall soon have to give up my paper job because of the intensity of homework, but I cannot do that unless I am assured of a regular pocket money. Hoping that you soon receive good news from the B.B.C. & that you are all right.

Lots of love from

Andrew

and John

John’s original postcard of 15 September 1940. (Author’s collection)

In those days, the war, which for a year had been a ‘sleeping war’, began with full force. Hitler invaded Belgium, Holland and France and within days swept away the resistance. The British were forced to withdraw their forces from France and the French gave themselves over to Hitler without any real resistance. Even their government backed Germany. In Britain the helpless government was swept away and Churchill, who did not compromise, became the leader of Coalition Government. I had hardly started working in the Pop Inn when the Germans began their aerial bombing of London. Somehow, it left me cold; I did not feel the danger. Shelters were built all over London. One night the bombing was so heavy, that Mum wanted to go into one of the street shelters. Her mother, who was terribly frightened, had not slept at home for days, but in a shelter in a nearby house. The weather was turning cold and despite blankets, which we brought with us, we were very cold, so we did not go down any more. A Hungarian friend of Uncle Eugene, who lived with us, was so frightened that he asked if he could stay in our bedroom while the bombs were dropping. One evening I went out into the street with him. I amused myself by watching his fear at every explosion. Your sweet Mum could barely wait for me to return to the house. We began to hear of more and more fatal incidents.

Uncle Eugene offered Mum the job of cashier, and as he offered an additional £1, this meant a considerable increase in our livelihood and especially that once more we could spend the whole day together, made us very happy. From early morning to late in the evening we were working, having lunch and dinner together again without expense and that made the morning to night, seven-day work-week hard work tolerable. At night we could hardly get home because of the bombs dropping. There were always explosions around us. Houses collapsed, burying the inhabitants. We used to run from the shop to the Underground and then from Notting Hill Gate station to our home, listening to the engines of the planes overhead.

Meanwhile, I received an invitation for an examination at the BBC. I had to translate from German to English and the other way round, take an intelligence test, and they examined my capabilities and knowledge base. After a long wait I got a notice that I passed and they put me on the waiting list. They would notify me if they needed me. I waited day by day with an anxious heart for their call; in the meanwhile I continued to work with greater strength and resolve at the Pop Inn. Sometimes the bombing was so severe that we could not go home. The Pop Inn had a basement restaurant and a basement passage and sometimes we spent the night there together with some of the other employees. We had a mattress there; Mum and I lay there arm-in-arm and slept like that. Sometimes her mother came in and slept with us.

In the restaurant, we started a so-called shelter-breakfast, which we served at 6 a.m. That was when people would emerge from the underground tunnels, where they hid from the bombs. At about 9 a.m., when breakfast was over and they began to clean the restaurant, we went home for an hour to bathe and change clothes, since we slept fully clothed. Gradually the restaurant got going, expenses diminished and income increased, but our wages did not rise. It was not sufficient to settle debts and the landlord seized our furniture. It looked as though we could not save the furniture, they would be auctioned, but the flat counted for little to us. You children were in the country and we were in the business all day.

Meanwhile we had other losses. We had to close the front door of the restaurant at night and we had to open the door under the gateway, which had to be covered with a curtain so as not to allow any light to get out. The door was next to the cash desk and in the cash, Mum had your beautiful crocodile handbag, which I had bought her back in Budapest. In it there was a gold cigarette lighter, with her monogram engraved, also bought in Budapest, as well as a little money and other small things. It was stolen by someone. Her heart was aching for them, but of course we could not even think of replacing them. I was in the habit of arranging the money and putting it into an envelope at the end of the day. Shortly after that the takings in the cash register were also stolen. It was not a big sum, but it was worth three weeks of my wages and I had to pay it back, so I got no pay for three weeks. I was getting used to these mishaps. Mum and I belonged to each other and that made up for everything in the world.

One evening, we were very tired and we wanted to go home to sleep in our beds. The bombing was so heavy, that we could not go out in the street. When we went home in the morning to bathe and change, we found our house in a terrible state. Most of the surrounding houses were in ruins. The street received a direct hit. In our house all the windows and doors were ripped out. The bed on which we were to sleep was covered with broken glass an inch high, with the shards and splinters from the doors and windows. God knows what would have happened to us if we had slept in them. It was a lucky escape. Since we could not live there any longer, we informed the bailiff that we have to take our furniture. He said he would have them taken for auction and, he would save for us whatever could be saved. He offered us and your grandmother the use of his own house, where he would give us a couple of rooms cheaply. He charged more than we had paid (rent) for the whole house. It was a very cold and uncomfortable house. He said that we would get our bedroom furniture back; they could not auction that according to law. He would also save the armchairs and sofa, a very attractive set, for us. It was only a matter of £40–£50. He explained that if the furniture were auctioned, then we would not have to pay the arrears, which we had for the furniture; that was the law and we would come out well from this. He was so pleasant and polite and seemed so helpful that we trusted him. Next day we moved to his house with our stuff.

You children surprised us with another visit. As much as we feared for you because of the bombing, we were that much happy to have you with us for a few days. We could not stop delighting in you. You had grown – and become British. One afternoon you went to visit your Aunt Edith’s family. The bombs were falling and you were not back in the Pop Inn. Mum could not bear the excitement and I was also anxious, but tried to calm her. Finally after another two hours, the phone rang. Then Mum at the nearest Underground station, and with wisdom and foresight she awaited a lull in the bombing. You children, especially Johnny, definitely enjoyed the thrill of the bombing and as we were sitting in the cellar of the Pop Inn, having our dinner, whenever we heard a bomb fall, Johnny shouted, ‘Come on’. Actually, it was not at all funny; each morning we read in the paper how many died as a result of the bombing.

Mum went to see the arbitrator to discuss the details of the auction and he assured her how much advantage we would get out of it. Johnny accompanied her and the arbitrator was so friendly, that he gave John half a crown, which he accepted with no little pleasure. Soon you returned to Melksham, and we were glad that you left the most dangerous zone. The difficulties with pocket money had eased, as now we could send a few shillings and secondly because you both began newspaper delivery every morning and were able to earn a little. Our poor boys had to get up at six o’ clock in the morning to deliver the papers before the start of school. We were very proud of you that you were earning money and besides they were among the teachers’ most favoured students and the best pupils in their classes. The children who went to the free school were usually of weak social standing, because only poor families sent their children to a free school. Nonetheless, as the future showed, you were excellent boys.