Evening's Empire: The Story of My Father's Murder (2 page)

Read Evening's Empire: The Story of My Father's Murder Online

Authors: Zachary Lazar

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #BIO026000

. . .

Ned Warren didn’t speak on the

CBS Evening News

of February 21. He was “not available to newsmen,” the reporter said.

Instead, the next person to speak was Attorney General Bruce Babbitt, future candidate for president, future secretary of the interior, at that moment riding the land fraud scandals in Arizona toward the state’s governorship. In 1975, he was gangly and wore glasses, and he hunched forward in his chair like a graduate student in a seminar room. “As a prosecutor,” he said, clearing his throat, “I’m not about to speculate publicly about who murdered Ed Lazar. But when a man with Lazar’s knowledge and background is murdered on his way to the grand jury, in the style in which he was murdered, it would be very coincidental to attribute it to some extraneous reason that is not related to those facts.”

The last man to speak put it more bluntly. He was another of Warren’s former business associates, a man named James Cornwall. He was tall and slightly jowly, with the sideburns and pomaded hair of the revivalist preacher Billy Graham—appropriate, since Cornwall had just become a minister himself. His suit and tie were of an expensive-looking subtle plaid, and he sat with one hand across his knee to reveal an elegant wristwatch. He seemed at ease, despite the fact that he was facing sixty-six counts of fraud, forty years in prison.

“Mr. Warren has told me he had the ability to pick up the phone and have people maimed or killed,” Cornwall said. “I believed it at the time, and I believe it now.”

On the afternoon before this story appeared on the

CBS Evening News,

more than four hundred people had attended my father’s memorial service at the Sinai Mortuary Chapel, which did not have enough seats for such a large crowd. There were my parents’ friends—the Korts and the Goodmans, the Finebergs and the Starrs, the Kobeys and the Shers—young Jewish couples, their children in school for the day. There were our next-door neighbors, Carol and Dick Nichols, who had taken me the night before with their sons, David and Craig, to a soapbox derby and spaghetti dinner to give me some time away from the confusion of adults crowding our house. There were members of the Jewish Community Center, where my parents played tennis, and of Temple Beth Israel, where my sister, Stacey, and I went to the annual Purim carnivals dressed in costumes my mother made out of towels, construction paper, and glitter. There were my grandparents on both sides, my aunts and uncles. There were the associates of Gallant, Farrow, and of Laventhol, Krekstein, Horwath and Horwath, the accounting firms my father had worked for before and after his stint in the land business. David Rich, the London born entrepreneur, was there. Ned Warren, though he had befriended my parents socially in the four years my father was his business partner, was not.

None of it made any sense to the people at the memorial service—this story of hit men in a stairwell, Ned Warren picking up a phone and ordering them there. It was something out of a movie—not even a realistic movie. There was the grief over the young man they’d all had a special liking for, and then there was the sense that his death would never seem real, that the sudden violence was so incongruous with his personality that the two could not be held in the mind at the same time. They thought about my father’s sly smile, the way he sometimes seemed to look at everybody from an amused distance, and then they thought about the front-page photo of his body slumped in a stairwell, the banner headline:

Grand Jury Witness in Probe of Warren Is Slain Gang Style.

His friends were in the furniture business or in real estate, practiced law or accounting or engineering. Their wives played mah-jongg and tennis and golf. Like my father, the men rooted for the ASU football team, took their families on vacation to Lake Havasu or San Diego. My father could be quiet. There was something he held in reserve, a mystery about him, even a romance, but there wasn’t crookedness, there wasn’t criminality. He was not your average CPA—women liked him, he had an adventurous side, he liked to drink. This adventurous side may have been why he got into a risky business like land development in the first place. But no one at the memorial service imagined he had “ties to the underworld,” or even knowledge of enough wrongdoing to be murdered. No one thought that.

In the parking lot outside, a reporter named Al Sitter from the

Arizona Republic

was taking down license plate numbers to see if any of them corresponded to figures of organized crime. The shame, added to the grief, was now beginning. Before long, my father would be appearing in news stories as the “lieutenant” to Ned Warren’s “Godfather,” the one man, now dead, who had “intimate knowledge” of the full extent of Warren’s criminality. Eventually, my father would come to look like a con man with a flashy suit and a Cadillac, or even a full-blown mobster, perhaps a relative of the Jewish gangster Hymie Lazar, as one line of thought ran. He was murdered twice in this way.

I remember his forehead being broad, with lines scored across it (lines that even then I thought I would inherit and by doing so know I was an adult). I used to try on his boots, stumbling toward the fireplace, with its mesh screen pulled closed by a thin chain. I remember the family room’s white shag rug, its console stereo with the plastic arm on which you could stack several records at once. I remember an avocado linoleum floor in the kitchen, a “passway” that looked into the living room (dark in memory, small and long). The living room, the family room, the kitchen—I remember the rooms. Whatever I write here about my father will have to be a kind of conjuration.

The evening the two detectives came to our door to bring us the news of the murder, my mother sent my sister and me to our rooms. From across the house, I could hear my mother laughing, a high-pitched, unabashed kind of laughter that sounded more and more illicit as it went on. When I went out to see what was happening, she was sitting on the couch, bowing and rising like a marionette, or as though someone was shoving her from behind, only to yank her back upright with her blouse in his fist. When she looked at me, she screamed, her face distorted. The scream was angry, personal, insane.

Almost from that moment, we stopped talking about it. As time passed, there were fewer and fewer occasions on which it made sense to try. To do so was to return on some level to my mother screaming in the living room.

I have always had two ideas: that one day I would have to write about my father’s story, and that if I ever did so I would never be able to write another thing again. What story could compare with his? The question was a more specific case of a larger dilemma: What could I ever do that would not seem trivial compared with what he went through?

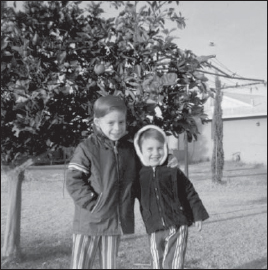

The author (right) and his friend and next-door neighbor David Nichols

It took me ten years to start. In the ten years I waited, some people who might have told me things died. When I at last flew to Phoenix, a week before Christmas 2006, I wasn’t thinking very much about what I was doing. I had put the trip together in such a hasty way that I had no time to consider my expectations. The pilot announced we were beginning our descent toward Sky Harbor Airport, and I was there. I had a stack of newspaper clippings, a few relevant books, the addresses of the people and places I was going to visit. I had appointments and dinners set up for every night I would be there. I would wake up at six-thirty every morning and go to bed at midnight, and every moment of that time I would be following a schedule, not thinking about it.

He was “not a big talker”—this was something I had learned from my interviews over the phone with some of my father’s friends. He “could keep a secret,” one of them said, “as you know.” My father’s onetime roommate Barry Starr had lived in the same apartment with him for three years and still felt he never knew him, that he remained a mystery. Phone calls would sometimes come to the apartment from a woman named Ruth, a woman who was otherwise a total secret. Only years later did Barry Starr learn that Ruth was Ed’s ex-wife, that they had a son together named Richard.

The story is not in one anecdote or newspaper article, but in two hundred anecdotes and newspaper articles. The story is in the relationship between eight thousand facts that for weeks and months seemed to have no relationship at all.

A young accountant takes a chance: he goes into business with a man who has “a not very savory reputation,” a man who in fact has a criminal record. No one knows exactly why he does this. This is the first mystery. It has something to do with his having a secretive side: he “could almost lead two lives,” according to one friend. It has something to do with his being adventurous, with his not being your average CPA.

A kind of conjuration. You look at the facts and see an intricate puzzle with some pieces missing. You establish a time line. You think of possible motives, of psychology. You piece together what you know and imagine how things could have played out in rooms forty years ago, most of the players long since dead.

PAGE TWO PX 183 94 EX TO

ANGELS PD ADVICED ONAT

LAS VEGAS SUBJECT ANTHONY JOHN SPILOTRO, FBI NUMBER 860 L42B HAD BEEN OBSERVED WITH LOS ANGELS SUBJECT

FBI NUMBER

AT STAS’S RESTAURANT, 5223 WEST CENTURY BOULEVARD, ENGLEWOOD, CALIFORNIA. SPILOTRO AND

ARE

OF

, FBI NUMBER

WHO IS UNDER INVESTIGATION AT LOS ANGELES IN CAPTIONED MATTER. LOS ANGELES PD INDICATED SPILOTRO AND

WERE OBSERVED MEETING WITH AN UN IDENTIFIED MALE AND FEMALE WHO OPERATED A 1973 WHITE OVER MAROON OLDSMOBILE BEARING ARIZONA LICENSE

LISTED TO

PHOENIX, ARIZONA. LOS ANGELES AND PHOENIX IND ICES NEGATIVE RE

. THE UNKNOWN SUBJECTS WERE FOLLOWED BY LOS ANGELES PD OFFICERS SOUTH ON INTERSTATE 605 TOWARD SANDIEGO AND CONTACT WITH AUTOMOBILE DROPPED IN VICINITY OF FOUNTAIN VALLEY, CALIFORNIA.