Every Day in Tuscany (24 page)

Read Every Day in Tuscany Online

Authors: Frances Mayes

Soon Mama Rose calls for music. Cuban music. She has the chairs pushed back and summons all of us to the samba. ONE, two, three, ONE, two three. She’s incredulous that many of us have lived so long without learning the samba. Well, we’ll change that tonight. Tonight’s the night. UNOS, dos, tres, she’s right, what was wrong with our lives that we did not samba? ONE, two, three …

Late, late, everyone drives out the impossibly narrow lane without incident. Must be the protective aura of wild white lilies, spot of miracles. As we climb the steps to our house, we hear voices and banging noises above us. “Isabella, bring in the candles.” “Carlos, find the girls’ bags.” “The fire is still going.” Then, faintly, we hear the five syllables of “Guantanamera,” the family singing as they clear up the party.

W

HEN WE WAKE

up tomorrow, they will be gone, gypsies stealing away in the dawn, leaving a large silence in Casa Caravita and a piazza strangely empty.

I came to Italy for the art, the cuisine, landscapes, history, architecture, wine, and the ineffable beauty. I stayed for the people. Cortona has a grand congregation of hearty, hospitable, generous souls. And not all of them are Italian.

I

L

F

ALCONIERE

T

ORTINO

S

OFFICE DI

C

IOCCOLATO E

P

ERE CON

S

ALSA DI

V

ANIGLIA

Il Falconiere Steamed Chocolate Cake with Vanilla Sauce

When we cook with friends at Silvia Baracchi’s school, Cooking Under the Tuscan Sun, we often whip up this very simple dessert. I never thought of chocolate as seasonal, but in Tuscany, it’s considered more appropriate for fall and winter. Seldom do you find it on a summer menu, perhaps because we have a plethora of plums, melons, and white peaches for hot-weather

dolce

.

With this, Silvia suggests a full-bodied sweet red wine with enough alcohol to “clean your mouth.” Her choices are a passito from Pantelleria or an aged Recioto. I’m partial to the passito from Arnaldo Capraia.

Serves 10

8 ounces (1 stick) butter, plus more for the ramekins

¾ cup flour, plus more for the ramekins

1 cup fine sugar

4 eggs

3 tablespoons rum (or Tia Maria)

2 tablespoons strong coffee

1 tablespoon plus 1 teaspoon baking powder

½ cup ground cacao (high-quality cocoa)

4 pears, peeled and diced (optional)

Vanilla Sauce (recipe follows)

Chocolate bar or chocolate-covered coffee beans

Preheat the oven to 250 degrees F. Butter and flour 10 ramekins and set aside.

Beat butter and sugar to a soft cream. Add eggs, beating them in one at a time. Add rum and coffee. Sift flour, baking powder, and cacao into a bowl, then incorporate this into the butter mixture. Gently fold in the pears, if using. Pour into the prepared ramekins, filling halfway. Bake in a bain-marie by placing ramekins in a baking dish and filling it halfway with boiling water. Bake for 10 minutes, then increase temperature to 350 degrees F and continue baking until set, about 15 minutes.

Unmold onto individual plates or simply serve in the ramekins. Spoon vanilla sauce over the cakes, and garnish with curls of chocolate (use a vegetable peeler) or chocolate-covered coffee beans.

V

ANILLA SAUCE

1 quart heavy cream

½ vanilla pod

8 egg yolks

4 tablespoons fine sugar

Heat the cream and vanilla pod to boiling, then quickly reduce heat. In a separate bowl, thoroughly beat together the yolks and sugar. Using a wooden spoon, stir the eggs into the cream and continue cooking on low, stirring constantly, for 5 minutes, until mixture slightly thickens and coats the spoon.

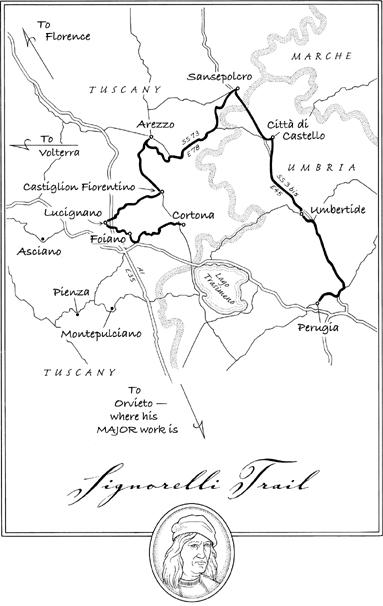

The Signorelli Trail

One’s destination is never a place but a new way of looking at things

.

—H

ENRY

M

ILLER

ART LOVERS COMB TUSCANY FOR CHANCES TO

ART LOVERS COMB TUSCANY FOR CHANCES TO

see the work of one of Italy’s greatest painters; from Florence to Arezzo to Monterchi to Sansepolcro, then over to Urbino, we travel the Piero della Francesca trail. We linger longest in Arezzo, where his only major fresco cycle remains in the church of San Francesco. Finally released from scaffolding after a fifteen-year restoration, the

Legend of the True Cross

is not his only work in Arezzo. Even some guidebooks miss the painting of Mary Magdalene in red on an inconspicuous wall in the Duomo. She’s a force to encounter as she stands regarding you with her hair wet from drying the washed feet of Jesus.

Her even more powerful counterpart,

La Madonna del Parto, The Madonna of Childbirth

, reigns over its own museum in nearby Monterchi. Also a full-length portrait, this incomparable painting shows the Virgin Mary, standing with her hand slightly parting the blue dress covering her ninth-month pregnancy. The gesture—one never seen before—suggests that she is about to open her dress and give birth before our eyes. Despite calm colors and her cooler-than-thou expression, she’s dynamite, the fuse lit.

Mothers-to-be visit her in supplication for safe birth, as they have for centuries. When she was removed from the Romanesque cemetery chapel to her new domicile, local women protested. I always wish, when I stand before this painting, that she could go back home. Too many people breathing on her, damp stone walls, humidity, and security drove her caretakers to secure the fresco. But surely the original setting could be made safe. To those who knew her in the chapel, where Piero intended for this homage to his own mother to live, the new one-painting museum seems stripped and soulless. Although the climate and air quality control protect the fresco, seeing her out of the rightful context seems like seeing an ethereal wedding dress in a thrift shop. Luckily, the sheer power radiating from the Madonna on the brink of changing the world manages to triumph over poor circumstance.

Sansepolcro, birthplace and home of Piero, is a top Tuscan town. I like the provincial market atmosphere, small shops, flat streets, and a trattoria with a mixed grill and antipasto selection so delicious that we always leave in a state of euphoria. I’m sure other notable dishes exit from the kitchen, but we always order the same thing. About once a week all year, Ed mentions Da Ventura’s succulent

stinco di vitello al forno

, oven-roasted veal shank, and their

maialino in porchetta

, crusty young pig spit-roasted with herbs. To step out of Da Ventura, after a

pranzo splendido

, and walk down the narrow street anticipating Piero’s paintings—there’s the essence of Tuscan travel. Such a lunch suffuses you with well-being. Then all you have to contemplate is whether or not

The Resurrection

is the greatest painting in the world.

La Pinacoteca Comunale, the Civic Museum, smells like chalky erasers in an old elementary school. The wan light inside falls benignly on Piero’s four (three?

San Ludovico

’s creator is disputed) paintings. The memorable face of

San Giuliano

looks vulnerable, shocked by whatever he’s looking out toward. Perhaps this is the captured moment when he realizes that an old spell has caught up with him. Like Oedipus, he fled his home because of an evil prophecy concerning his parents. He made a marriage and life far away. While he was on a voyage, his unsuspecting parents found his new home and hospitable wife. They were sleeping when he returned. Thinking his wife had taken a lover into their bed, he murdered his parents, thus fulfilling the prophecy.

The majestic

Resurrection

dominates. Christ emerges from the tomb, his eyes already

al di là

, beyond the beyond. You can’t help but recall the same otherworldly look in the eyes of the

Madonna del Parto

, as she fingers the opening to her dress at an equally defining moment. His left foot steps up onto the edge of the tomb, the right still inside. Spring has arrived in the background behind his emerging foot, while winter remains behind the foot inside the tomb. He’s dressed in lilac-rose dawn colors as he prepares to step into the new day. Four guards sleep below him, oblivious to the miracle. Legend says that the second one from the left is Piero—is that a goiter on his neck?—depicted as completely conked out.

The Resurrection

is particularly precious to Sansepolcro, which means Holy Sepulcher. At the time of the painting’s conception, viewers also saw a local symbolism. Piero’s town was experiencing a growth spurt and revival (resurrection) after freeing itself from Florence’s clutches. The artistic patrimony of Tuscan small towns continues to stagger me. What if my hometown, Fitzgerald, Georgia, owned such masterpieces?

In an everlasting tribute to liberal arts education, a World War II American pilot on a bombing mission in the area vaguely remembered a professor speaking of the small village of Sansepolcro as the home of great Renaissance paintings. He spared the city.

Seeing Luca Signorelli’s

Crucifixion with Saints

in Sansepolcro makes me think

he

needs a trail to follow. For me, he is

the

Renaissance painter who seems to step ahead of his time. His revelry in depicting the male body, the life-force he infuses into form, and, most of all, his passion for individual faces give him a visceral energy. He loved muscles, movement, tension, feelings, force. Gertrude Stein said of her obsession with her characters, “I wanted to see what made each one that one.” Luca would concur. Faces! Each so revealed. In his work a recurrent blond woman obviously obsessed him. So close an observer was he that you see his locals in the piazza today. Another quality catapults him toward the contemporary sensibility. He often strikes the viewer with the impression of more action continuing outside the painting’s borders. He cuts off the drama at the edge of the frame at the last minute, instead of keeping action framed with space around. He seems precocious. In

Italian Painters of the Renaissance

, Bernard Berenson agrees: “His vision of the world may seem austere, but it already is ours. His sense of form is our sense of form; his images are our images. Hence he was the first to illustrate our own house of life.”

I had sensed the vivacity imparted by his dynamic composition but had not articulated the effect I felt until I read and pored over the prints in

Luca Signorelli

by Tom Henry and Laurence Kanter. From them, too, I found

what

Signorelli is

where

, and which ones (especially in Città di Castello) are not totally by Luca’s hands. The authors are rigorous art historians but also top detectives. They’ve traced several panels and predella sections to the paintings they once joined. I was jolted to learn that two panels of Luca’s

Lamentation

in Cortona’s San Niccolò now live in my home state at the High Museum in Atlanta. Please, give them back.

Besides dissecting what’s authentic, what’s not (and what might be both), the authors catalog and comment on all of Signorelli’s work.

They opened my eyes to Signorelli’s very smart use of architecture in his paintings. How brilliant to observe that the left-side light source in the

Annunciation

in Volterra came from Signorelli’s conceit of using the three actual windows to the left of the oratory altar where the painting hung. So it appeared as though natural light bathed the angel. And Signorelli also repeated the oratory’s vaulted ceiling on the Virgin’s side of the painting. This blending of the place itself with the painting subtly created a feeling of intimacy for the viewer. (Since the

Annunciation

was removed to the Pinacoteca Civica, these connections are lost.)

In frescoes, sometimes a figure actually is stepping or leaning outside the painted frame. So much to admire. I love the details Luca often places in his foregrounds: a dropped red hat, a glass of wildflowers, hammer and skull, a lizard, an open book—each a tiny still life to savor and contemplate.

W

HILE

E

D DRIVES

home from Sansepolcro, I jot down a basic three-day Signorelli route. Luca’s trail leads to the wilder side of Tuscany, with a dip into Umbria. For anyone not passionate about art, this

gita

delivers anyway, for each town has righteous piazzas, good coffee, and people always worth watching.

Museum hours are usually dependable, but churches open at erratic hours. Sometimes you can ring for a custodian, sometimes the side doors are open, and often the local tourist office will be able to help. When I want to be sure a church is open, I check for the hours of mass and visit just as the service ends.

Start in his native Cortona, which is graced with a trove of Signorellis. Most remain in great condition since they never had to travel. A tour of his paintings in the Museo Diocesano, San Niccolò, San Domenico, Santa Maria del Calcinaio, and Museo dell’Accademia Etrusca e della Città di Cortona (MAEC, also known as the Etruscan Academy) almost comprises a tour of the town.

The best place to start is the Museo Diocesano before Luca’s magnificent

Lamentation at the Foot of the Cross

. By my lights, this intricate work ranks as one of the high moments of the Renaissance. I isolate every face, every detail, and see a rare perfection, then regard the whole breathtaking composition. In the left distance, crucifixion takes place and on the right, resurrection, with Christ triumphant within a gold almond-shaped light. The cross, with dripping blood, bisects the painting—but, typical of Luca, the measurement is slightly off center. In the foreground, the deposed Christ lies with his head in the lap of Mary, his lower legs sprawled across the legs of Mary Magdalene, seated on the ground. A crouching woman holds his arm tenderly and leans to kiss his palm. One reason this painting is so moving is that three women are in physical contact with the magnificent body just removed from the cross. Other sorrowing holy women and men look on, and each face reflects a very particular emotion. Their sumptuous clothing gave Luca a chance to paint the folds and drape and grace of fabric. The gold leaf, dusty greens, tarnished copper browns, burnished coral, and ashy blues of the entire painting present a palette of complete harmony. An idealized village on a lake centers the background and reminds us subtly that somewhere, life goes on unperturbed by the momentous scene before us.

Another great Luca in this museum shows Christ giving communion bread to his apostles. If you focus on each face, the intensely individual portraits show a gamut of emotions. You see Signorelli’s passion for human grace—and the opposite: Judas, closest to the viewer, furtively slips the Host into his satchel. Fox face, sly eyes, he’s the only one disengaged in the scene.