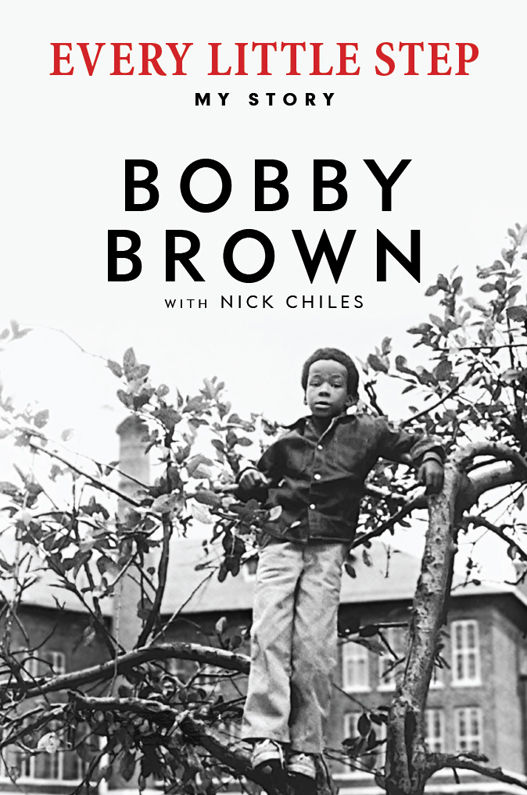

Every Little Step: My Story

Read Every Little Step: My Story Online

Authors: Bobby Brown,Nick Chiles

This book is dedicated to the little boy in the tree.

“Live fully, create happiness, speak kindly,

hug daily, smile often, hope more, laugh freely,

speak truth, inspire change, and love deeply.”

To my mom and dad; brothers, sisters, nieces, nephews,

aunts, uncles, my friends, and most importantly my

children; and my lovely, beautiful wife, Alicia; thank you

for your support through all the years.

This is only the beginning.

—BOBBY BARISFORD BROWN

I’ve lived nearly all of my life under the glare of the public spotlight.

I became famous with New Edition when I was just fourteen.

As a solo artist, I released an album before my twentieth birthday that many have noted as altering the course of R & B music, stamping the term “new jack swing” onto the public consciousness. I was just the second teenager in history—after Stevie Wonder—to hit the top spot on the

Billboard

chart.

In my twenties, I fell in love with the biggest music star on the planet. Our marriage kept more than a few gossip tabloids in business. Watching the hell couples like Jay Z and Beyoncé are put through these days, I can’t even imagine what it would have been like being married to Whitney Houston in the age of Twitter and Instagram.

Whitney’s death was devastating not only to me but to

the entire nation. And I still am trying to grapple with the incredible pain and trauma of losing my daughter Bobbi Kristina.

But despite my three decades in the harsh media glare, the public has never really heard my story. What Bobby Brown is thinking, what he’s doing, what he did do, what he didn’t do—for the most part what has been said about me has been speculation from people who didn’t know what they were talking about. It’s usually been wrong—and usually intended to make me look bad.

To some degree, I understand. That’s how public images work. They slap a label on you and that’s who you are—the facts be damned. Early on, I cemented my reputation as the “bad boy of R & B.” And it stuck. For the most part, I embraced it—for thirty years. It was fun—when I was young and foolish. But now that label feels too one-dimensional. Too much has happened and enough time has passed. I feel like I owe it to myself and the ones I love and will always love to be honest. I finally think it’s time for me to show the world who I really am. I want to tell the real story.

MY (MUSICAL) ROOTS

When I stretch my mind back to my earliest memories, music was always there. While other little kids in Boston dreamed about playing for the Red Sox or the Celtics, I dreamed about stepping onto a stage and thrilling the crowd with my singing and dancing.

Music was constantly playing in my house, with everybody throwing their own sound into the mix. With six children and my mother and father, we’re talking about a lot of sound. Whenever my dad, Herbert, came home from work, he would put on some blues, or maybe funk. Then he would start dancing and acting crazy. We would be laughing so hard our stomachs would hurt. My late father is still the funniest man I’ve ever met. Not Eddie Murphy or Martin Lawrence. Not Kevin Hart.

Herbert Brown

. And my mother actually sang in a duo with her brother Robert—whom I was

named after—when they were younger, so she had performing in her blood.

But I think the biggest musical influence on me was my grandmother, my mother’s mom. She had an apartment on the first floor in the Orchard Park projects; we lived right above her on the second floor. My grandmother had a massive record collection. I knew her apartment was a place I could go and lose myself in music. It became my sanctuary, where I could get away from the noise and craziness of my large family and go exploring in her records.

My grandmother loved Duke Ellington, so that’s where I would usually start. I didn’t mind the big-band jazz because I could jitterbug to it. I liked all types of music though; I’d play the Chi-Lites, the Manhattans, Blue Magic. This was the mid-to-late seventies (I was born in February 1969), so these groups were still in their heyday, before disco hurt their popularity. From there, I would gradually move into the funkier stuff. My God, funk was everything to me. James Brown, Bootsy Collins, Parliament, Rick James—damn, I’d lose my mind. I had no idea how influential Rick James would later become in my life.

When I put on the funk, I’d start the dancing, working out the routines I was always putting together. My grandmother would be watching me from the kitchen, where she was cooking, and she’d have a big smile on her face as she watched me move. I’d be getting down and she’d be getting a big kick out of it. For me, the best thing about dancing

was making her smile, making her laugh, knowing she was enjoying what I was doing. Looking back on this time now, pleasing my grandma was probably where I got this drive to do whatever I can to please my fans. My grandmother was my first fan.

Eventually my badass brother, Tommy, would come into the apartment. He would get mad that my grandmother was paying me way more attention than him—so he’d have to fuck up everything. He’d pick up a big stack of records and throw them all over the floor—then he’d call out to my grandmother in the kitchen, pointing at me and saying, “Ooh, look what Bobby did!”

He was nine years older and a lot bigger than me, so I had to take his mess. But I’d get so mad. I knew it would all stop when I grew up to be as big as him. I would stand there all mad, thinking,

You just wait a few years . . .

Everybody in my family thought they could sing. If you asked us, we’d tell you we were the second coming of the Jacksons. That was actually my father’s master plan, to make us into a Boston version of the famous family group. The Browns of Boston. Since we were four girls and two boys, the Browns would have looked quite a bit different than the Jackson 5. And my brother was too shy to sing in public, so he was the DJ. But the girls? You couldn’t tell them

nothing

. Not a thing. But although my family members played around with singing and performing, I was the only one who was adamant:

This is what I want to do with my life.

My parents tried to encourage my musical talent by buying me a couple of cheap instruments. First my mother bought me some drums when I was in the third grade. They were cheap as hell, with skins made out of material not much more durable than typing paper. My little sister, Carol, made sure those drums didn’t last more than a week or so. One day I came home from school and saw that she had beat them up, putting big holes in the snare, the bass and the tom-toms. Yeah, they were cheap, but they were still mine. So of course I had to beat

her

up.

A year or so later my mother bought me a bass guitar. She knew I had always loved listening to the bass, the smooth rumbling coasting along at the bottom of those records I enjoyed listening to. I played around with that cheap bass for many hours, tinkering in my room with those strings. But I never got any lessons to go along with it, so eventually I laid it down—and didn’t pick it back up until several years later, when I got lessons on a New Edition tour from one of the funkiest bass players who ever lived, Mr. Rick James.

Hitting the Stage

My parents were huge fans of James Brown, as most of the black community was in the early 1970s. James was filling black people with a sense of pride with memorable records like “Say It Loud, ‘I’m Black and I’m Proud,’” which came out in 1968, the year before I was born. Though I don’t re

member, my parents say I really responded to James Brown’s music even when I was a baby. And when I was three, James unknowingly gave me my first chance to take over a stage. My parents brought me along when they went to a James Brown concert in 1972 at a well-known club called the Sugar Shack on Boylston Street. The Sugar Shack hosted all of the top R & B acts in the 1960s and ’70s when they came through Boston. At a certain point during his show back then, James would welcome kids on the stage to dance and entertain the crowd. Apparently that was all the invitation my three-year-old self needed. I’m told that I immediately grabbed the attention of the crowd and had them screaming with my James Brown–like dance moves. It would be a telling baptism for me as a performer—for the next four decades, grabbing the crowd would become as important to me as breathing.

It’s fascinating for me to watch my son Cassius do the same thing when I bring him out on the stage now. The boy loves to perform, and it’s clear he has inherited my all-consuming desire to please the crowd. It’s deep in his blood. When I take him with me to a Bobby Brown or a New Edition show, I sometimes bring him out to dance with me to “My Prerogative.” The boy swears he’s the reincarnation of Michael Jackson; he even told me that one day. He devours Michael’s music, requesting that we play songs from different Michael periods—Jackson 5 Michael,

Off the Wall

Michael, older Michael. Sometimes he’ll call me into the living room and make me sit down.

“Daddy, watch this new move,” he’ll say.

Then he’ll spin, kick out his leg, and launch into some intricate Michael steps. The whole family will be cracking up, but I’ll also be thinking:

Damn, I did the same exact thing when I was his age

—except it wasn’t Michael Jackson I was mimicking, it was James Brown. Cassius gets it honestly; his mother, my wife, Alicia, was also a dancer when she was younger. In fact, Alicia starred in one of the most influential videos of the nineties—she was the bikini-clad saxophone player who was the centerpiece of Teddy Riley’s “Rump Shaker” video with his group Wreckx-N-Effect. I’m certainly not going to push Cassius into the music business, but if he really wants it I’m not going to stand in his way either. And in the meantime, he’ll be getting singing lessons, piano lessons, and whatever else I can think of to keep encouraging his talent.

The first public performance that I actually remember came several years after the Sugar Shack, when I was about nine. I entered a talent show at a local club called the Hi-Hat in Roxbury, the predominantly black neighborhood in southern Boston where Orchard Park was located. In fact, I did so well that I scared the hell out of myself.

Let me explain: Growing up in the seventies in Boston, it seemed like talent shows were everywhere. The Hi-Hat was a nightclub on the weekdays and a community center during the weekends. My oldest sister, Bethy’s, friend Norma hosted a lot of the talent shows, so it was only a matter of time before Bethy put me up on that stage. She knew I could dance

and sing. But there’s a difference between imitation and stepping out on that stage with all those eyes staring at you. The funny thing was, even though I was always doing imitations and spending those long hours at my grandmother’s place listening to her records, I still didn’t have any idea that I had actual singing talent.

My sister and her husband decided what I should look like for my big performance. They put me in white pants, a white shirt, and a white applejack hat, with a head full of bouncy California curls. I looked like a baby pimp. Don’t forget—this was 1978. We were just coming out of the heyday of blaxploitation movies like

Super Fly

and

The Mack

. It wasn’t hard to see where my sister was going with that look.

My song selection was “Enjoy Yourself” by the Jacksons, which had been a big hit the previous year—the first big hit by the Jackson family after they left behind Motown and the name “the Jackson 5.” Even Janet sang on “Enjoy Yourself” as a little ten-year-old. I guess that was the first time I connected with Janet— it wouldn’t be the last.

The “stage” at the Hi-Hat wasn’t really a stage. It was more like a dance floor with space cleared away in the middle for the performers. My sister’s friend Norma had asked my sister to serve as a judge, so she was sitting in one of the three judges’ chairs set up next to the stage area. When I say that I didn’t know that I could sing, what I mean is that I had spent so much time imitating other singers I hadn’t yet tried to figure out what my own singing voice would sound like.

And I wasn’t sure how people outside of my family would react to my singing. I got my answer real quick. I hit the first few notes of “Enjoy Yourself” and started doing my Jackson-inspired dance moves, just beginning to get into the song—and all of a sudden the girls began screaming.

I had no idea why they were screaming, but I was scared to death. So what did I do? I froze. I stopped singing, looking around with what I’m sure was a crazy expression on my face. Then I did what was probably the most embarrassing thing I could possibly do in that situation—I ran and jumped in my sister’s lap. Imagine that: a big-ass nine-year-old, jumping into a woman’s lap. And on top of it all, a nine-year-old dressed like a mini pimp. I guess in my mind my sister’s lap was the most comforting place I could be at the time.

The announcers tried to get me to come back.

“Come on back out, little Bobby Brown. Come sing that song, little Bobby. You look all sharp. Come finish the song!”

But I was not having it. I was not budging. My sister kept saying, “Leave him alone. He doesn’t want to go out now.”

But she was also whispering to me, trying to get me back out there. I just kept shaking my head. Then she’d wait for a few acts to go on and ask me again. “You want to do it now?” But I had made up my mind. I told her, “I’ll come back next week. And I’ll be better when I come back.”

As I predicted, I came back the following week—and I killed it. I was wearing the same white outfit, sporting the same curls, singing the same song. I remember having the

curls redone, sitting at the stove while one of my sisters straightened out my hair with the hot comb. I think she even burned me. It was worth it.

Life in the Projects

Though we lived in the projects, I don’t think we had any idea that the projects were supposed to be a bad place until we watched the show

Good Times

. Though it fell on harder times in the 1980s during the crack epidemic, in the 1970s the Orchard Park projects for our family weren’t nearly as depressing as the Chicago projects where the Evans family lived. There were plenty of fights, confrontations, the threat of violence—but our bellies were never empty and nobody ever tried to kick us out on the streets. Both of my parents had good jobs—my mother, Carole, was a teacher and my dad, Herbert, was a construction worker building big skyscrapers downtown—and there was plenty of love flowing through the Brown household. We were in a good place. Anytime he got the chance, my father would show us the buildings he had helped to construct. I remember his pointing out the Prudential building in particular. He was proud of the work he had done, and he liked to use these buildings as a way to pass along lessons to us, especially to me and my brother.

“A workingman is everything,” he would tell us. “When you got work to do, you work hard, do your job and go on home.”

I’ve never forgotten that one.

The Brown family basically

ran

Orchard Park. I don’t ever remember having reason to feel threatened or afraid of anybody or anything. There were six of us and I was the second youngest, so I had plenty of older siblings to look out for me. My older sisters were beasts—they were all cute and the biggest gangsters and pimps were always trying to get with them. Plus, I had a bunch of cousins around too. So that meant nobody was going to even think about messing with a Brown. There were just too many of us.

Our family was one of the few in Orchard Park that had both a mother and a father in the household, so we were looked upon as the brown-skinned Brady Bunch. And my mother was one of those generous Mother Teresa types who would welcome and care for anybody who was in need. It sometimes looked like she was cooking for the entire projects. We’d have random people from the streets sitting at our dinner table or sleeping on our floor because my mother had offered them a hot meal and a warm room. Everybody loved Carole Brown.

In addition to my family, the other major force in my life at the time was music. This was at the start of the 1980s, so a new music form was just bursting onto the scene: rap. Ironically, considering how big an influence it would soon have on my life, the first rap song I ever heard was “Rapture” by Blondie, the New Wave band fronted by a skinny blond woman named Deborah Harry. It was recorded in 1980,

right around the time that Grandmaster Flash was cooking up the origins of rap in New York City and the Sugarhill Gang was sending out the first real rap song on vinyl. Deborah Harry even name-checks Grandmaster Flash during her verses, though none of us really knew what the hell she was talking about. But soon after, I heard the more authentic pioneers like Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five and I fell in love. I fully embraced this new music, with its aggressive, pulsating sound and potent style. I couldn’t get enough. I even adopted my own rap persona, a character I called “Flash B”—no doubt influenced by my rap idol Grandmaster Flash. I told everyone to call me Flash B; when I was about eleven, I even got a belt that said “Flash B” on the buckle.