Every Single Second (3 page)

Read Every Single Second Online

Authors: Tricia Springstubb

“I can’t believe it,” she said softly.

Me neither,

Nella almost said.

My head’s spinning! My heart’s breaking! How could they do this to us?

But she didn’t want to be like Angela. Weak, watery Angela.

“It’s not like we have a choice,” she said.

Her clumsy, ocean-liner feet started running and didn’t

stop even when she was up the hill and through the tall iron gates of the cemetery. And she kept on running, though the stitch in her side was killing her. She didn’t stop till she got to the statue of Jeptha A. Stone, 1830–1894, where she collapsed in a miserable heap.

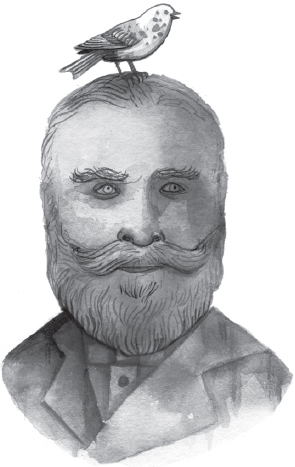

What the Statue of Jeptha A. Stone Would Say if It Could

I

know this child. Her father is my faithful caretaker. Once a year, that good man climbs a ladder and expunges bird excrement from my shoulders and pate.

I, Jeptha A. Stone, am no fan of avian creatures.

When yet small, this girl helped her father plant the spring flowers.

Help

is a generous word. She was a clumsy child. Her father is a patient man.

I have not seen her in years. Her legs resemble a baby giraffe’s. Still clumsy, I fear.

I sincerely wish she would not cry.

I, Jeptha A. Stone, am no fan of tears.

As you might guess, given my place of residence, tears are impossible to avoid. Tears, wails, laments. This place makes humans leak.

Sitting atop my magnificent marble pedestal, I am buffeted by other things besides grief. In winter, brutal winds

assail me. Snow piles atop my noble cranium, and occasionally, icicles drip from my handsome, aquiline nose.

In summer, the heat beats down. The birds . . . well. You know what birds do.

Yet we statues must maintain our dignity. It is our solemn duty to be stoic. Imperturbable.

Above all, silent.

T

he new baby, Kevin, wasn’t even walking yet the morning Mom poured her coffee down the drain. The next day Nella had to pack her own lunch, because her mother was too busy throwing up.

(What were they thinking, making all those babies? Or more to the point, not thinking? It would be years before Nella asked questions like that. In first grade she still dwelled in the Land of Innocence, where her family was as much a given as rain or trees or God.)

This was the year that the balloon she got at the Feast slipped from her hand and tangled high in a tree, and

when Anthony climbed up to get it, he fell and hit the sidewalk.

Anthony got a scar from that fall. A small slash over his left eye. Nella loved that scar. She secretly pretended he’d been in a sword fight to save her. Afterward, they galloped away on a golden horse with a silver mane.

Nella planned to marry him someday. In Real Life.

Anthony let Angela hold his hand even when his friends were around. (Not that he had many friends.) Nella longed to hold his hand too. When she imagined her hand in his, something inside her turned over. A little engine began to hum.

In first grade they learned to tie their shoes, to read, to recite the Our Father and Hail Mary. Their teacher, Sister Rosa, was a jolly old woman with round red cheeks—Nella and Angela were sure that was how she got her name. Sister liked to crush the two of them together in a hug and say they were her PB and J. “I can’t have one without the other!” she’d crow.

(If only you could store up happiness, Nella would think years later. Dig a happiness hole, or keep a happiness piggy bank, saving up for when you ran out.)

Anthony walked them home every day. As they tightrope walked the bocce court wall, he sat and drew. A castle, a tiger, Nella with no front teeth. Once they found the

skeleton of a small bird and he drew that, every weightless bone. He was never in a hurry to get home.

“You’re an angel,” Mom told him. “You should be named Angelo!”

“I’m named after my father.” Anthony squared his shoulders, like just the mention of Mr. DeMarco set him at attention. “I’m carrying on the family name. It’s an honor and a responsibility.”

Mom’s eyes clouded as if he’d said something sad. Then she put her arms around him, though by now he was too old to hug.

(Years later, Clem, no fan of hugs, would tell Nella,

When it comes to hugging, your mom doesn’t discriminate based on race, religion, sex, age, or national origin.

)

T

he cemetery was home to flocks of angels, granite or marble, fierce and sword wielding or cherubic and adorable.

It was also an arboretum, so the trees had identifying labels, just like the dead people.

RED MAPLE WHITE OAK EUROPEAN BEECH

STONE WADE PIERCE

More than a hundred years ago, boatloads of Italian craftsmen had arrived to build the cemetery’s massive stone wall, lay out the gardens and curving paths, carve the angels and monuments and soaring obelisks. Settling nearby, they

re-created the villages they’d left behind. They built the church and the school. They planted grapevines and fig trees, danced at each other’s weddings, and wept at each other’s funerals. Nonni and her husband, PopPop, came some years later, but things hadn’t changed much. Nonni loved to tell about the old days, stories sweet and quaint as folk tales.

PopPop had worked in the cemetery. So had his son. And now his son, Nella’s father, was the head groundskeeper.

Leaning against Jeptha A. Stone’s monument, she remembered helping her father plant the spring flowers. He’d lift the seedlings from their plastic pots, and she’d tuck them into the wide flower beds. It was like setting zoo animals free from their cages. Afterward they’d walk home together, her small hand in his rough one. When people teased her father about how closemouthed he was, Nella was confused. It seemed like she and he were always talking, though he hardly said a word.

It was terrible how fast things could change. One second to the next. Like God flipped a coin.

Only of course He didn’t. He had a plan.

Now Nella wiped her eyes. Jeptha A. Stone threw his self-important shadow across the grass and down the slope. If statues could see, he’d have the place’s best view. Compared to sorry old St. Amphibalus, Jeptha A. Stone had

piercing eyes. His wide brow wrinkled in thought. His coat fell from his wide shoulders in soft folds.

STONE

was chiseled into the monument base. His name, of course, but it also seemed like a description.

This is how lifelike a block of cold stone can be.

As Nella stood up, a small, yellow-flecked bird landed on Jeptha’s big bald head. Bright-eyed, it sang a merry

tra la la

, like it had laid the world’s most colossal egg. In spite of everything, Nella had to laugh. It almost looked like the high and mighty Mr. Stone shuddered.

That night she went to Clem’s house. The Patchetts were what certain people in the neighborhood considered Invaders. Clem’s parents were professors at the university at the top of the hill. Her father dealt in quasars and quantums. He was like Einstein, only with normal hair. Mrs. Patchett wrote award-winning poetry that Nella couldn’t understand any more than she could her baby brother’s babble. They lived in the old public school, now converted into hip, green-energy condos. Their place had creaky

wood floors and tall windows that rattled. A faint, ghostly smell of chalk and wet wool mittens still swirled through the hallways. The Patchett Parents loved old stuff—old rugs, old books, old bikes with fat funny tires. This was a different kind of old stuff from Nonni’s, though. No doilies here. No porcelain ladies balancing baskets of grapes on their heads.

Nella and Clem were in Clem’s bedroom. Sitting on the floor, Nella looked around at posters of Wolverine, Magneto, and Dr. Who. There was a chart of the elements, and a picture of a colossal pearl caught in a volleyball net. The space-time continuum, Clem called it. It was hard for Nella to draw the line between real and sci-fi. She was never sure what percentage of her best friend’s mind was anchored in reality.

“It’s so freaking cool. A leap second. Like a leap year, only nano. They actually

add

a second. They

extend

time. They

manipulate

the clock!”

Witness: Clem was talking about time. Time, at a time like this.

“Who are

they

? Wait, never mind! Not now. Clem, we have to talk about next year.”

Clem crossed the room and lifted the top off her hedgehog’s house. Yes, there was also a hedgehog, Mr. Tiggywinkle, Mr. T for short. His face was adorable, but as

for the rest of him?

Gentle

and

decisive

—those were the keywords in a hedgehog relationship. GAD. Mr. T’s black button eyes blinked and his nose twitched. He and Clem had similar hairstyles, come to think of it.

“They want me to go to that magnet school. The math and science one.”

This was not news. Her parents had wanted Clem to go there this year, but by the time Clem took the admission test, she and Nella had become good friends. And Clem, whose test scores were normally off the charts, had scored abysmally low. Mysteriously, wondrously low.

“But . . .” Nella swallowed. “You flunked the admission test.”

“You’re allowed to take it every year. And this year they’re adding an extra test date, since all these schools are getting closed.” Clem lowered her prickly pet back into his house. “You can take it too.”

Nella stared at Clem’s digital clock. The red numbers stayed the same, stayed the same. In this room, time had died.

“I’d never get in.”

“Don’t say that.” Clem’s face suddenly loomed two inches away. Upside down, hanging off the bed. “Anyway, even if I get in, I don’t have to go. I get to choose.”

How did you score parents like that? How did you win the super jackpot in the parent lottery?

These were the sort of useless questions Nella’s brain produced. Clem’s square black glasses dangled from her forehead. She smelled like grapefruit, a smell that was nice but also a little dangerous.

“They don’t believe in coercion, except on things like doing drugs or riding my bike without a helmet. Even if I get accepted, it’s still my choice.”

Nella scrambled up and hung her head over the edge too. The ceiling became the floor. The desk waved its legs in the air. Her upside-down heart skittered in her chest.

“So,” she said. “All is undecided.”

“And if I was Time Ninja, I’d freeze it right”—Clem jabbed the air—“here.”

“Huh?”

“When you choose one thing, you dis-choose a gazillion others.

Making

a choice isn’t the powerful part.

Having

a choice is.”

Choices—Nella was terrible at them. Not that she got much practice, considering her life.

“But,” she said, “what do you think you’ll do?”

“I don’t know.”

“Are you faking?”

“Death to fakers!”

“Slow, lingering, torturous death.”

“Fart!” they yelled together.

FART. Fakers Are Really Tacky, one of their secret two-person societies.

Nella’s head was a blood bomb. She did a backward somersault onto the floor, then poked Clem in the belly. Or where a belly would be if she wasn’t built like a breadstick.

“Your head will explode,” Nella said. “And don’t think I’m going to clean up all those spattered brains.”

Clem laughed and slithered to the floor. They polished off their papaya juice.

“One thing is decided,” Clem said. “Sam Ferraro’s in like with you.”

“Oh right. And Sister Mary Anne has a secret love life. She met this guy on match.com. He likes red wine. And Latin, of course.”

“Too bad he’s so conceited.”

“Sister’s boyfriend?”

“Sam Ferraro!” Clem shouted.

Why was she making this up? Boy-girl stuff didn’t even interest her.

“Everyone knows he likes Victoria and her thong-wearing you-know-what,” said Nella.

“His brain was so addled, he couldn’t stop staring at you.”

“Staring like he saw a Komodo dragon.”

“Komodo dragons are adorable!”

In the living room, Clem’s parents sat side by side with their laptops. Her father wore a bow tie. Nella had never seen him without it. Probably he wore it to bed. Her mother had swept-back, raven-black hair with a white stripe on one side. Cool. They were the definition of cool.

Clem snuggled between them. Mrs. Patchett tilted her laptop so Clem could see.

“Okay, bye,” said Nella.

They all waved. One two three.

“Remember to think about the Leap Second!” called Clem.

“Okay,” promised Nella.

The what?

Sinatra Torture poured out Mama Gemma’s open door.

“I did it my way!”

If Nella heard that song one more time, she might actually, literally die. In the evening air, the spice of Mama Gemma’s pizza battled the sugar of Franny’s doughnuts, both smells bathed in grease. Grease—she was in love with it. No wonder her chin was a pimple farm.