Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (13 page)

c.

persistently positive blood cultures in spite of treatment

d.

invasive paravalvular infection causing conduction disturbances, or a paravalvular abscess or fistula (detected by TOE)

e.

recurrent major embolic phenomena, although this is controversial (an isolated vegetation is not in itself an indication for surgery).

Factors suggesting a poorer prognosis

1.

Shock.

2.

Congestive cardiac failure.

3.

Extreme age.

4.

Aortic valve or multiple valve involvement.

5.

Multiple organisms.

6.

Culture-negative endocarditis.

7.

Delay in starting treatment.

8.

Prosthetic valve involvement.

9.

Staphylococcal, Gram-negative and fungal infections.

Differential diagnosis

1.

Atrial myxoma.

2.

Occult malignant neoplasm.

3.

Systemic lupus erythematosus.

4.

Polyarteritis nodosa.

5.

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis.

6.

Pyrexia of unknown origin.

7.

Cardiac thrombus.

Prognosis

Prior to antibiotic use, this was an invariably fatal disease. Currently, more than 70% of patients with endogenous infection survive, as do 50% of those with a prosthetic valve infection. Intravenous drug users have a good prognosis.

Prophylaxis

Confusion between rheumatic fever and endocarditis prophylaxis is common. Rheumatic fever prophylaxis consists of long-term, low-dose antibiotic administration. Prophylaxis against endocarditis requires high-dose, short-term treatment only in patients with a very high risk, namely a previous episode of endocarditis, a prosthetic heart valve, a congenital heart malformation (unrepaired cyanotic heart disease, repaired cyanotic heart disease with residual defects or recent surgery within 6 months) or a cardiac transplant with valve disease. According to the latest 2007 American Heart Association guidelines, all other lesions no longer require prophylaxis.

Prophylaxis is also recommended according to the Australian (Heart Foundation) guidelines for:

•

complex congenital heart disease, including patients who have had repair operations using shunts or artificial material and have persisting shunts (e.g. VSD repaired with Gortex, but with residual shunt)

•

Aboriginal patients with any intermediate or high-risk lesion.

Prophylaxis regimens are as follows (recommendations from

Therapeutic Guidelines – Antibiotic

):

1.

Dental procedures (e.g. gum cleaning) or oral surgery

– amoxycillin 2 g, 1 hour before the procedure. For patients unable to take oral antibiotics, use ampicillin IV or IM just before the procedure. If the risk is high, give ampicillin and gentamicin as described below. For those allergic to penicillin, clindamycin 600 mg given orally 1 hour before the procedure is adequate.

2.

Gastrointestinal or genitourinary procedures:

no prophylaxis is recommended.

Remember that the effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis has not been proven. Patients need to be reminded of the need for good dental hygiene and regular dental review.

Congestive cardiac failure

This is a common therapeutic problem, but it may be a diagnostic problem. It is uncommonly the only major problem in a long case.

The history

1.

It is important first to find out what may have precipitated episodes of cardiac failure. Precipitating problems include:

a.

arrhythmias (especially atrial fibrillation)

b.

discontinuation of medications – usually the diuretic (particularly important)

c.

myocardial infarction

d.

anaemia

e.

infection and fever

f.

thyrotoxicosis

g.

anaesthesia and surgery

h.

pulmonary embolism

i.

high salt intake, drugs that cause salt and water retention (e.g. traditional NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors) or excessive physical exertion

j.

pregnancy.

Note:

Chronic lung disease can be a cause of, or a precipitating factor for, right and left ventricular failure.

2.

Then ask about the symptoms of left ventricular failure (e.g. dyspnoea, orthopnoea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea) and right ventricular failure (e.g. oedema, ascites, anorexia and nausea). Ask about symptoms of ischaemic heart disease (e.g. angina). These may help distinguish dyspnoea caused by lung disease from that caused by cardiac failure.

3.

Enquire about the history of previous heart disease:

a.

hypertension

b.

ischaemic heart disease – infarcts, angina

c.

rheumatic or other valve disease

d.

congenital heart disease

e.

cardiomyopathy

f.

previous cardiac surgery (e.g. coronary artery bypass grafting, valve replacement or resection of an aneurysm)

g.

cardiac transplantation.

4.

Find out about coronary risk factors, in addition to age and male sex, including:

a.

hyperlipidaemia

b.

hypertension

c.

smoking

d.

diabetes mellitus

e.

family history of early coronary heart disease

f.

use of oral contraceptives or premature onset of menopause

g.

obesity

h.

physical inactivity.

5.

Ascertain the risk factors for dilated cardiomyopathy:

a.

excessive alcohol intake

b.

family history of cardiomyopathy

c.

haemochromatosis.

6.

Ask what medications are currently being taken.

7.

Ask what investigations have been undertaken – particularly echocardiography, stress ECG testing, nuclear studies and cardiac catheterisation.

8.

Find out how the disease affects the patient’s life and ability to cope at home (e.g. climbing stairs, sexual difficulties, etc.). Remember to classify the patient according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) guidelines.

NYHA classification

I

No limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause angina/dyspnoea.

II Angina/dyspnoea on mild activity.

III Angina/dyspnoea on moderate activity.

IV Angina/dyspnoea at rest.

The examination

1.

Perform a detailed cardiovascular system examination.

2.

Look particularly for signs of cardiac failure, the underlying causes of the problem and any precipitating factors (see

Fig 5.4

).

FIGURE 5.4

Extremely lateral position of IJV, found with ultrasound. G E Malcom, C C Raio, A P Poordabbagh, G C Chiricolo, Difficult central line placement due to variant internal jugular vein anatomy.

Journal of Emergency Medicine

, Fig 2. 35(2):189-191. Elsevier, 2008, with permission.

3.

Look for a pacemaker or defibrillator box.

4.

Note wasting as a result of cardiac cachexia.

5.

Take the blood pressure lying and standing. Treatment with ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers often results in mild hypotension.

Investigations

1.

Chest X-ray film

(see

Fig 5.5

). Look for cardiomegaly and chamber size (e.g. left atrium), cardiac aneurysm, valve calcification, sternal wires suggesting previous cardiac surgery, signs of lung disease and pulmonary congestion.

FIGURE 5.5

Alveolar pulmonary oedema. When the pulmonary venous pressure reaches 30 mmHg, oedema fluid will pass into the alveoli. This causes shadowing (patchy to confluent depending on the extent) in the lung fields. This usually occurs first around the hila and gives a bat’s wing appearance. These changes are usually superimposed on interstitial oedema. A lamellar pleural effusion (arrow) is seen at the right costophrenic angle where Kerley ‘B’ lines are also evident. The Canberra Hospital X-Ray Library, reproduced with permission.

2.

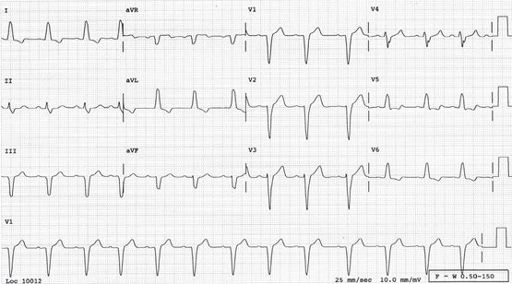

ECG

. Look for arrhythmias, signs of ischaemia or recent or old infarction (

Fig 5.6

), left ventricular hypertrophy and persisting ST elevation (aneurysm). Left bundle branch block is a common ECG finding in these patients (

Fig 5.7

). The ECG is rarely entirely normal in a patient with heart failure.

FIGURE 5.6

Sinus rhythm. There are Q waves from V1 to V5. This is diagnostic of an extensive old anterior infarct, which is likely to be the cause of this patient’s heart failure.

FIGURE 5.7

Sinus rhythm. Left bundle branch block (LBBB). The QRS complexes may widen further as heart failure progresses. LBBB is a common finding in heart failure but is not diagnostic.

3.

Electrolytes and creatinine levels

. To exclude hypokalaemia (as a cause of arrhythmia), hyponatraemia (which may indicate severe longstanding cardiac failure, a poor prognostic sign) and renal failure.

4.

B-type natriuretic peptide level (BNP; previously called brain natriuretic peptide)

. Although there is doubt about the reference range, a definitely elevated level may help distinguish cardiac from non-cardiac dyspnoea. Since BNP falls when heart failure is treated, trials of monitoring BNP are underway as a means of assessing the adequacy of cardiac treatment.

5.

Haemoglobin value

. To exclude anaemia as a precipitating cause.

If the diagnosis is not already obvious, consider

dilated cardiomyopathy

. Investigations for this include those outlined below.