Execution: A Guide to the Ultimate Penalty (37 page)

The scaffold was 20 feet long and 15 feet wide, the platform being 10 feet high. A long beam, 10 feet above the platform, ran from one end to the other, and beneath it were two long drops, each 6 feet by 4 feet. Above each drop, two hempen ropes were suspended, each having a noose formed of nine turns and a knot. The traps themselves were held level with the platform by stout vertical uprights beneath them. When the prisoners, securely bound, and blindfolded with white caps, were in position on the traps, the captain-in-charge clapped his hands three times, four soldiers knocked the uprights away, and the drops fell as planned.

The assassin Charles Julius Guiteau, who murdered President Garfield in July 1881, met a similar end, albeit in a more conventional style, standing on the trap, a black cap on his head. The noose was secured, the signal given, and the bolts were withdrawn. Instantly, the trap fell, aided by a weight attached by a rope to its underside and passing over a pulley preventing it from swinging back and striking the descending victim. Guiteau fell 6 feet and swung motionless, heartbeats being still faintly detectable 14 minutes later, and pulse action 16 minutes after the execution.

American hangings didn’t always pass without mishap, of course, any more than in other countries. In 1880, in Washington DC, James Stone violently attacked his wife and sister-in-law with a razor, almost decapitating them. Found guilty at his trial and sentenced to death, he had a last meal, a whole fried chicken, potatoes and trimmings, washed down with coffee. On the scaffold he stood quietly, blindfolded by the black cap; the hangman operated the trap; the victim duly fell; and then, horror of horrors, the head was jerked off the shoulders.

The body, blood spurting from the open neck, fell to earth; the head clung to the noose for a moment, then dropped, splattering blood on the timbers on its way. Despite the severance, the doctor detected pulsations of the heart up to two minutes later, and on picking up the head and removing the cap, he reported that the victim’s features were composed, but that the lips continued to move.

The medical conclusion was that Stone was so overweight that the tissues of the neck had grown weak, thereby allowing the rope to break through the skin and fat, to fracture the spine and sever the head. Some of those present expressed the opinion that other than the appalling spectacle – of which the victim could not have been aware – this was a quicker way to die than swinging from the rope, a thought-provoking hypothesis indeed, and one which had, a century or more earlier, inspired Dr Guillotin.

As befits a nation claiming the highest, widest, heaviest and best of everything, it should not be forgotten that it also holds the record for the most people hanged on one gallows.

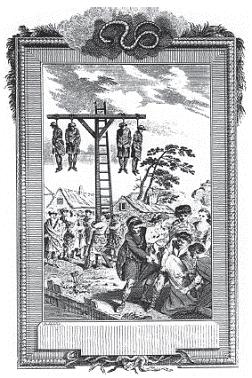

In 1862, along the frontier of Minnesota, a band of Sioux and other tribal Indians attacked and massacred nearly 500 settlers, men, women and children. Pursued by the cavalry, battles ensued, and, of the surviving Indians, 38 were sentenced to death as an example to the others. And at Mankato, on 28 December 1862, surrounded by hundreds of troops, they mounted the huge scaffold. Bound, white caps over their heads, nooses encircling their necks, they chanted and swayed in unison. One tap was sounded on the drum. The supporting props were knocked away and the trap fell with a reverberating crash, leaving the bodies of 38 human beings suspended in the air.

America’s contribution ends on a humorous note. In 1864 gangs of robbers and murderers attacked ranchers and gold-miners, and five of them were due to be hanged in Virginia City. Lined up on the scaffold, they were being prepared for their dispatch when a bystander, sympathetic towards the condemned men despite their misdeeds, asked the guard who had just settled a noose about a felon’s neck: ‘Did you feel for the poor man when you put the rope about his neck?’ The guard, whose friend had previously been murdered by the gang, looked quizzically at his questioner: ‘Yes,’ he said drily, ‘I felt for his left ear!’

The scaffold in Woodstock, Canada, in 1890 merits some attention. It consisted of two uprights 7 feet apart, the cross-beam joining their tops extending 6 feet further out at one end, beyond the scaffold, so being about 14 feet above the ground. The condemned man stood between the two uprights – there was no trap – and the rope from the noose passed through a pulley immediately above his head, along the cross-beam and through another pulley located at the far end of the beam extension.

There it was attached to a cube weighing 350 pounds which had been raised by means of a block and tackle into a position a foot or so below the cross-beam, and secured by a chain held in place by an iron pin.

To operate, the pin was withdrawn, allowing the weight to fall and, in doing so, taking up the slack, the sudden impetus jerking the victim’s neck so violently that fracture of the spinal column brought almost instant death.

Another variation to the traditional method of hanging was practised in Iraq. Following the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in 2003, one of the dictator’s 12 official hangmen, Saad Abdul Amir, related how, during the previous 11 years, he had executed thousands of victims, despatching them through the hatch two at a time, twice a week, after sunset on Wednesdays and Saturdays. His technique involved using two nooses per victim. The well-tried tradition of having two assistants stationed beneath the trap doors to pull on the victim’s legs, perfected by some of Tyburn’s finest operators, was still maintained. Saad Abdul added that Saddam would not only personally sign each execution order, which was always written on yellow paper, but would frequently attend executions, the rope-handling efficacy of the hangman duty hardly being improved by his presence!

Four men being hanged together and a woman and her illegitimate child are drowned

‘Carefully, according to custom, they tucked his sleeves under his knees to prevent him from falling backwards, for a noble Japanese gentleman should die falling forward.’

This Japanese word literally means ‘belly-cutting’, and hara-kiri is generally considered to be a form of suicide rather than a judicial punishment. This conception of suicide, however, applied only in cases where high-ranking officials or members of aristocratic families, having committed a serious crime, chose to die in that manner in order to avoid the disgrace of criminal proceedings being taken against them. Should their misdemeanours reflect adversely on the integrity of their emperor, they would receive from the royal palace a condemnatory letter and a jewelled dagger; no further hint would be necessary. Where the offenders were obliged to take their own lives by ‘royal decree’, half their worldly goods were forfeited to the Crown, but by contrast their estates remained those of their heirs should they exit this life voluntarily.

Criminals, too, occasionally elected to die by hara-kiri, thereby enabling their families to save face in the community. This self-imposed and self-inflicted capital punishment, whether by aristocrat or commoner, called for the utmost courage and almost superhuman determination in its execution. And as in many other facets of Japanese life, ceremony played a major part.

It usually took place in a temple, in which a low dais had been constructed. On a mat thereon the victim, clad in a white robe, knelt and prayed. Then, stripped to the waist, he took the weapon, a short, razor-edged sword or dirk, and plunged it deep into the left-hand side of his stomach, pulling the blade across horizontally. Turning the weapon, he then drew it upwards, and, as he did so, the official duly appointed, the Kaishaku, stepped forward and decapitated the already dying man.

For a description in all its horrific detail one need look no further than an eye-witness account, published in the

Cornhill Magazine

earlier during the last century, of the last moments of an officer of the warship

Prince of Bizen

, responsible for the bombardment of the foreign settlement of Kobe.

‘After a few minutes of anxious suspense, Taki Zenzaburo, a stalwart man of thirty-two years of age, with a noble air, walked into the hall attired in his white dress of ceremony with the peculiar hempen cloth wings which are worn on great occasions. He was accompanied by a Kaishaku and three officers who wore the ‘Zimbaori’, or war surcoat. The word Kaishaku is one which our word ‘executioner’ is no equivalent term. The office is that of a gentleman; in many cases it is performed by a kinsman or a friend of the condemned, and the relationship between them is rather that of principal and second than that of victim and executioner. In this instance the Kaishaku was a pupil of Taki, and was selected by the friends of the latter from among their own number for his skill in swordsmanship. With the Kaishaku at his left hand, Taki Zenzaburo advanced slowly towards the Japanese witnesses, and the two bowed before them; then drawing near to the foreigners they saluted us in the same way, perhaps with even more deference, and in each case the salutation was ceremoniously returned.

Slowly and with great deference the condemned man mounted on to the raised floor, prostrated himself twice before the high altar, and seated himself on the felt carpet with his back to the altar, the Kaishaku crouching on his left-hand side. One of the three attendant officers then came forward bearing a stand of the kind used in temples for offerings, on which, wrapped in paper, lay the ‘wakizashi’, the short sword of the Japanese, nine inches and a half in length, with a point and an edge as sharp as a razor’s. This he handed, prostrating himself, to the condemned man who received it reverently, raising it above his head with both hands, and placed it in front of himself.

After another profound obeisance, Taki Zenzaburo, in a voice which betrayed just so much emotion and hesitation as might be expected from a man who is making a painful confession, but with no sign of fear either in his face or manner, said: ‘I, and I alone, unwarrantly gave the order to fire on the foreigners at Kobe, and again as they were trying to escape. For this crime I disembowel myself, and beg you who are present to do me the honour of witnessing the act.’

Bowing once more, the speaker allowed his upper garments to slip down to his girdle and remained naked to the waist. Carefully, according to custom, they tucked his sleeves under his knees to prevent him from falling backwards, for a noble Japanese gentleman should die falling forward.

Deliberately, with a steady hand, he took the dirk that lay before him and looked at it wistfully, almost affectionately; for a moment he seemed to collect his thoughts for the last time; then stabbing himself deeply below the waist on the left-hand side, he drew it slowly across to the right side and, turning the blade in the wound, gave it a short cut upwards.

During this sickeningly painful operation he never moved a muscle of his face. When he drew out the dirk he leaned forward and stretched out his neck. An expression of pain for the first time crossed his face, but he uttered no sound. At that moment the Kaishaku who, still crouching at his side, had been keenly watching his every movement, sprang to his feet, poised his sword for a second in the air – there was a flash, a heavy ugly thud, a crashing fall – and with one blow the head had been severed from the body.

Complete silence followed, broken only by the hideous noise of blood gushing out of the inert heap before us, which but a moment before had been a brave and chivalrous man. It was horrible!

The Kaishaku made a low bow, wiped his sword, and retired from the raised floor, and the stained dirk was solemnly borne away, a bloody proof of the execution. The two representatives of the Mikado then left their places and, crossing over to where the foreign witnesses sat, called us to witness that the sentence upon Taki Zenzaburo had been faithfully carried out. The ceremony being at an end, we left the Temple.’

Hara-kiri was officially abolished in 1868, but still survives voluntarily, and is practised by both men and women, though in the case of the latter only the throat, and not the stomach, is cut.