Execution: A Guide to the Ultimate Penalty (43 page)

SCOTTISH MAIDEN

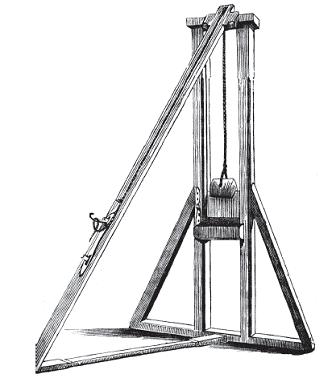

Reference to the Halifax gibbet has already been made, and its apparent efficiency must have been noted in 1565 by the Earl of Morton, Regent of Scotland, on passing through Halifax during one of his return journeys from London. Back in Edinburgh he had a similar machine built, it becoming known as the Scottish maiden, the words perhaps originating from the Celtic

mod-dun

, meaning ‘the place where justice was administered’.

The structure resembled a painter’s easel, though having two parallel uprights, and was about 10 feet high. The victim’s neck was supported by a cross-bar 4 feet from the ground and was pinned down by another cross-piece above it. A sharp, lead-weighted blade ran in the grooves cut down the inner surfaces of the uprights, being held in place at the top by a peg attached to a long cord. When this was pulled, the blade fell, severing the victim’s head.

It performed its gruesome task for a century and a half, decapitating more than 120 victims, among them plotters involved in the 1566 murder of David Rizzio, the arrogant secretary of Mary, Queen of Scots. But the most unfortunate victim of all was surely the Earl of Morton himself, who perished beneath its blade on 2 June 1581 at the City Cross in Edinburgh.

The Scottish maiden also embraced a father and son. Archibald Campbell, Marquis of Argyll, nicknamed the ‘glae-eyed marquis’ because of his severe squint, was executed for treason in May 1661. His son, the ninth earl, also named Archibald Campbell, bowed his neck beneath the pendant blade in 1685, commenting wryly that ‘it was the sweetest maiden he’d ever kissed’.

That unfortunate nobleman was the last victim of the maiden, for it was dismantled in 1710 and is now on display in the National Museum of Antiquities in Edinburgh.

The Scottish Maiden

SEWN IN AN ANIMAL’S BELLY

In this century current methods of execution are well known – hanging, the electric chair, the gas chamber, and so on – it being accepted that to a greater or lesser extent they are carried out with as much respect for human decency as possible.

But in the time of the Greek writer Lucian (

ad

117–180) many more bizarre and revolting methods were in force, one of which he included in his

Dialogues of the Dead

. It was the account of proceedings held to decide the penalty to be inflicted on a Christian martyr, a woman, one official saying:

‘We must discover some sort of death whereby this maiden may endure long-drawn and bitter torment; so let us kill this ass and afterwards cut open its belly, and after removing the inwards, shut up the girl inside in such a way that only her head be left outside (this to prevent her being entirely suffocated) while the rest of her body be hid within the carcass.

Then, when this has been sewn up, let us expose them both to the vultures – a strange meal prepared in a new and strange manner. Now just consider the nature of this torture, I beg you. To begin with, a living woman will be shut up in a dead ass; then by reason of the heat of the sun will she be roasted within its belly; further, she will be tormented with mortal hunger, yet entirely unable to destroy herself. Yet other features of her agony, both from the stench of the dead body as it rots, and the swarm of writhing worms, I say nothing of. Lastly, the vultures that feed on the carcass will rend in pieces the living woman at the same time.’

All shouted assent to this monstrous proposal, and unanimously approved its being put into execution.

SHOT BY ARROWS

The early Danes dispatched their victims by this means, prolonging the suffering by aiming their arrows at non-vital parts of the body until finally administering the coup de grâce. Edmund, the last King of East Anglia, was shot to death in this manner by Vikings in

ad

870.

SPANISH DONKEY

‘A further bizarre touch was the addition of a carved horse’s head and tufted tail, accessories which, hardly surprisingly, failed to raise a laugh from the unfortunates who were sentenced to ride the appliance.’

The Spanish donkey was another penalty which, like keel-hauling and flogging, could be administered to a greater or lesser extent, either as a minor punishment for a slight misdemeanour or as a sentence of death for a serious crime. And as in the case of those two punishments, this one could also result in an unintentional death, depending on the stamina of the miscreant.

Just as keel-hauling and flogging were widely applied in the armed forces of many countries, so the Spanish donkey was used predominantly for the maintenance of military discipline. Used by the Spanish army until the nineteenth century, the torture consisted of seating the victim, his hands tied behind him, astride a wall, the top of which resembled an inverted ‘V’. Weights were then attached to his ankles, these being slowly increased until the victim’s body split into two. Should a suitable wall not be available, a smaller version about 4 feet long and 6 feet high was constructed on a platform with small wheels to facilitate its transport.

This type of device also existed in the British army, though, instead of a cumbersome wall, the appliance was made by nailing suitably shaped wooden planks together in the shape of a horse, its backbone forming a sharp ridge about 8 or 9 feet long, thereby allowing more than one delinquent to be punished at a time; greater verisimilitude was created by mounting the effigy on four legs, these standing on a wheeled platform.

A further bizarre touch was the addition of a carved horse’s head and tufted tail, accessories which, hardly surprisingly, failed to raise a laugh from the unfortunates who were sentenced to ride the appliance. Instead of weights, muskets were tied to their legs, in order, it was wittily said, to stop the mount from unseating them! Not unnaturally the device was called the wooden horse.

Like many quaint English traditions, the wooden horse found its way across the Atlantic, it being reported that ‘Garret Segersen, a Dutch soldier, for stealing chickens, rode the wooden horse for three days, from two o’clock to close of parade, with a 50-pound weight tied to each foot, which was a severe punishment’. The report went on to state that at least one death was caused by the vicious device in colonial America, this occurring in Long Island.

Due to the risk of death, even when prescribed only as a minor punishment, it was realised that, unlike floggings and similar corrective measures which healed fairly rapidly, the injuries caused by the horse could incapacitate a soldier and make him permanently unfit for army duties, and so the practice was eventually discontinued.

The

cheval de bois

was also used by the French army, which, despite the national sense of chivalry towards the fairer sex, inflicted it ‘on ladies of easy virtue caught in the barracks’.