Expiration Date (5 page)

Authors: Duane Swierczynski

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Hard-Boiled, #Action & Adventure, #Noir

The Thing with Three Fingers

I woke up on a hospital gurney with a skull-crushing headache and a raw throat. People in blue smocks brushed against my bed, which was jammed up against a wall in a busy hallway. Every time the bed jolted it sent another sledgehammer tap on the spike slowly inching its way to the center of my brain. My mouth tasted like dirty pennies. I wanted to throw up.

After a while I rolled over and used the metal rails to pull myself up to a sitting position. I ran my fingertips across my five-day stubble, patted my chest, my belly. All there. I was still wearing my nylon shorts and T-shirt. The ring and pinky fingers were still attached to my left hand.

But both were dead numb, like I’d fallen asleep on them. They wouldn’t bend either. Not unless I cheated and used my other hand, which I noticed was now hooked up with an IV needle. Good Christ, what had happened last night?

Somebody blew past my gurney, flipping through papers on a clipboard.

“Hey,” I called out, and the guy stopped midstride.

“Yeah?”

“Where am I?”

“Frankford Hospital, man. You O.D.’d.”

“I

what

? How did I get here?”

“Girlfriend brought you in. She was pretty freaked out. I were you, I’d think about help. But I can’t be the first person to tell you that.”

And then he continued on down the hall.

O.D.’d?

I needed to get out of here. I grabbed the IV needle with the three good fingers of my left hand, yanked it out, sat up. Some blood shot out, so I pulled up the tape and recovered the puncture. I hated needles.

So this was Frankford Hospital. I hadn’t been inside this place in years—and that had been the old building, which had been razed and replaced by this one.

My grandpop was here somewhere, on one of these floors. For a moment I thought about stopping up to see him, just to get the obligation out of the way. I could kill two birds with one stone—recover from overdose, check; visit grandfather, check. But then I remembered I was shoeless, hungover and confused. I needed a shower and a nap. A nap to last at least a week.

And I needed to make sure Meghan was okay, and that she didn’t think I was a complete dick.

Once I was reasonably sure I wasn’t going to puke, I swung my legs over the side of the gurney then slid off. My first few steps were wobbly, but okay. I walked out of the hospital. Nobody tried to stop me. And why would they? I was just a junkie in nylon shorts and a threadbare T-shirt. Hell, I was doing them a favor.

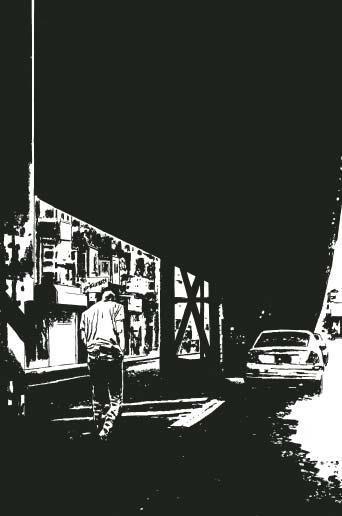

I made the four-block walk back to the apartment, carefully avoiding beads of glass on the sidewalk. One old woman, wrapped in a dirty gray shawl and a badly stained and ripped dress, stared at me from the doorway of a long-closed delicatessen. There was shock and anger in her eyes.

“It’s you! You finally showing your face around here?”

Welcome home, Mickey Wade.

“You son of a bitch!”

I kept walking.

Meghan had locked the door. But she’d also thought to put the key under the doormat, bless her soul. I could only imagine what I’d put her through last night. No wonder she hadn’t stuck around.

Inside the apartment the sofa bed was still pulled out, covers mussed, pillows twisted up and askew. Boxes had been pushed out of the way. I must have blacked out in bed. She panicked, called 911.

I pressed my face against the pillow that had been hers. It smelled like her—vanilla and the sweetest slice of fruit you can imagine. So at least that part hadn’t been a dream. Meghan had really been here last night.

And somehow I’d managed to O.D. on beer and Tylenol.

There was nothing in Grandpop Henry’s microscopic fridge except two Yuenglings from the night before. I didn’t feel like walking back downstairs to buy something sensible for breakfast, like a Diet Coke or bottle of Yoo-Hoo. So I twisted open a beer. Maybe a beer would outsmart my headache. And if the headache wasn’t fooled, the cold would at least soothe my throat. Besides, isn’t this what unemployed writers are supposed to do? Drink a cold beer at eight in the morning?

I opened my laptop to search the job boards. There wasn’t much to search—not for unemployed journalists, anyway. In years past, an out-of-work journalist could fall back on teaching or public relations. But now actual teachers and public relations flacks were duking it out, death match–style, for the same jobs. Journos didn’t stand a chance.

My eyelids felt like slabs of concrete, so I gave up, drank a few more sips of beer and then crashed on the couch—bed. Somewhere in the haze of unconsciousness I heard my cell ring once. I reached up with my left hand, fingers still numb, fumbling for the phone, half-hoping it was Meghan. Nope; my mom. I hit the ignore button and closed my eyes. She probably wanted to know if I’d found a job yet. Or visited my grandpop yet. Or stopped being a screw-up yet.

Sometime later, the rumble of the El woke me up.

I was more than a little alarmed to discover that the two fingers on my left hand were

still

numb. Why hadn’t the feeling come back yet? Maybe I whacked them on something on my way to the hospital, causing some nerve damage. Which would be fantastic. What did an unemployed writer need with fingers, anyway?

I rolled off the couch, starving. But Grandpop’s cupboards were stocked with nothing but old-man junk food—a couple of cans of tuna, cream of tomato soup, a box of stale crackers and a foil bag containing some potato chip particulates. Maybe I could stick my face into the bag, inhale some nutritional value.

I settled on the tuna, but it took me awhile to find a can opener. I finished one can and then ate every single stale flakeboard cracker, washing them down with tap water, which tasted like salt and metal.

Okay, enough stalling. I grabbed my cell from the top of the houndstooth couch. It was time to call Meghan and start my awkward apology. And maybe find out what the hell had happened.

First I listened to my mom’s message:

“Mickey, it’s your mom. Just checking in to see how you’re making out over there. Have you stopped by the hospital to see your grandfather yet?”

Yes, Mom,

I could truthfully tell her,

I visited the hospital first thing this morning.

“Anyway, maybe you could come up to have dinner with Walter and me this weekend. He’s been asking about you. Let me know and I’ll pick you up.”

Walter is her boyfriend. I couldn’t stand him. She knows this, but pretends not to know this. I hit erase.

The cell was down to a single bar, so I looked for a place to charge it. I found a black power cord that snaked across the floor, around a cardboard box and into the back of something hidden under a stack of file folders. To my surprise, it turned out to be a silver Technics turntable.

The thing looked thirty years old. I hit the power button on the silver tuner beneath it, then ran my index finger under the needle and heard a scratching, popping sound. It worked.

I fished out one of my father’s albums—Sweet’s

Desolation Boulevard

—and listened to “The Six Teens” while I finished off the warm Yuengling I’d opened a few hours ago.

This was the first time I’d listened to any of these albums.

The LPs were my dad’s. Mom gave them to me on my twenty-first birthday. She told me I used to love to look at them when I was a toddler. Now, I haven’t owned a record player since I was eight years old—a Spider-Man set, with detachable webbed speakers. So all these years I’ve had no way of listening to these albums. But now and again I’d open the three boxes full of old LPs and thumb through them, taking the time to soak up the art.

You can have your tiny little CD covers, or worse, your microscopic iPod jpegs. Give me LP covers, like George Hardie’s stark black-and-white image of a blimp bursting into flames from

Led Zeppelin I.

Or the floating tubes on the front of Mike Oldfield’s

Tubular Bells.

The freaky black-and-white lion’s head on the cover of

Santana,

which I’d often misread as having something to do with

satan.

The Stones turning into cockroaches on

Metamorphosis.

Grand Funk Railroad, Iron Butterfly, The Stones, Lou Reed, Styx—these were all bands that I loved purely for their cover art.

As for the music inside…well, my mileage varied. You could only listen to “In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida” so many times, if you know what I mean.

But I would look at the art and think about my dad bringing the albums home from the record shop—probably Pat’s on Frankford Avenue—putting his headphones on, listening to the music, staring at the covers himself, letting his imagination wander, dreaming of making his own records someday.

But he never did make a record. He was killed before he had the chance.

While my cell charged I showered, pulled on a T-shirt and jeans, then ventured out for some food. First, I needed money. There was a battered ATM near the Sav-N-Bag market all the way down Frankford Avenue, near the end of the El tracks. The walk was as depressing as I imagined it would be. Shuttered storefronts. Abandoned shells of fast-food chains that became clinics for a while before they shut, too.

At the ATM I quickly checked my surroundings for possible muggers, then quickly shoved in my card and pressed the appropriate keys. I asked for $60—just enough to buy some cold cuts, maybe a few cans of soup, some boxes of cereal. Bachelor staples.

My request is granted, but my receipt tells me I only have $47 to my name.

Whoa whoa whoa. That didn’t make any sense. It should have been more like $675. Where was my final paycheck from the newspaper? Today was Friday. Payday. My last one. Possibly ever.

By some miracle I got the

City Press

’s assistant HR guy on my cell. Funny that the paper can afford to get rid of writers and art designers but never management. The paper currently had a three-man human resources department; with me gone, there was exactly one news reporter on staff. Exactly which humans would these HR people be resourcing?

The assistant HR guy—Howard—explained that my last check has been all but wiped out by sick days I owed the paper.

“No no. That can’t be right.”

Howard assured me it was.

“I never took sick days. I was a reporter—I was out of the office a lot. You know, doing reporting.”

Howard told me his hands were tied.

“Look, Howard, seriously, you’re wrong about this. Check with Foster.”

Howard asked who Foster was.

“Star Foster. The editor in chief? You know, of the paper?”

Howard told me it wouldn’t matter if he spoke with Foster, or what she might say. He had my time sheets in front of him. He goes by the time sheets.

“You don’t understand. I want…no, I

need

my entire final paycheck.”

Howard told me he was sorry, wished me all the best, then hung up.

Which meant that unless I changed Howard’s mind, I had exactly $47—plus the $60 I just withdrew—to last me pretty much forever.

Like most of America, I had nothing saved. Every month I danced so close to zero, my checking account was more like a temporary way station for a small amount of cash that passed between a newspaper and a series of credit card companies, corporations and utilities.

My economic strategy thus far had been simple: if I start to run out of cash, I slow down on spending until the next payday. That strategy, of course, depended on there

being

a next payday.

Mom was not an option. Not yet, anyway. Placing me in Grandpop’s apartment was her brand of help—a gentle suggestion, not a handout. Asking for a loan now would just confirm my mother’s lifelong theory that the Wadcheck men could never hang on to anything: marriage, fatherhood (my grandfather), songs, recordings, his life (my father), a relationship, a career (me). I was on my own.

I had written hundreds of articles and interviewed everyone in the city, from the power brokers to crooked cops to addicts squatting in condemned ware houses. And for three years, thousands of people had read my work and knew my byline. The name on my debit card was even starting to get recognized in bars and restaurants.

Are you the Mickey Wade who writes for the

Press?

Nope. I’m just some idiot standing outside a supermarket in my old neighborhood with no job and about sixty bucks in my pocket.

“You bastard.”

I turned, and it was the old lady from this morning, leaning against the stone wall of the supermarket. She looked even rattier up close. Bad teeth, rheumy eyes. She must hang out on Frankford Avenue all day, waiting for losers to cross her path so she can mock them. She pointed at me with a crooked, bony finger.

“The day’s going to come when you’re going to get what’s coming to you.”

Oh, how I’ve missed Frankford.

A copy editor at the

Press

named Alex Alonso once told me about the three basic things humans needed to survive. He’d worked one of those Alaskan fishing boat tours where you endure an exhausting, nausea-filled hell at sea for two months in exchange for a nice payday at the end. Alex said it was pretty much eighteen hours of frenzied labor, followed by six hours of insomnia. And for two months he consumed nothing but apples, peanut butter, cheap beer and cocaine.