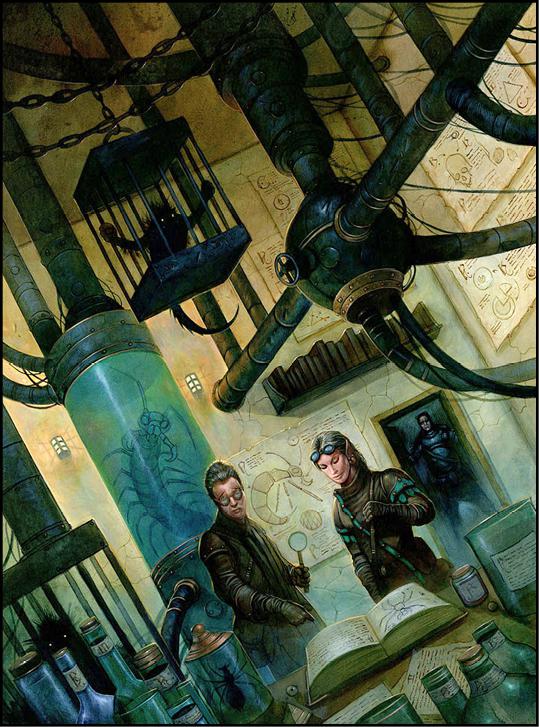

Extraordinary Zoology (2 page)

Lynus held the textbook with a measure of reverence as he thumbed through it. The binding and cover had survived the enthusiastic mauling at the left head of Professor Pendrake’s pet, so the volume was clearly sturdy, but it was more than just a book. It was a symbol of what he hoped to attain in life; full of knowledge, it had survived the worst and was too cherished to be cast aside for a newer edition. Even though the professor could afford to replace this tome a hundred times over, he still kept it around, telling students like Lynus to “read around the tooth marks.”

A tricky proposition. The punctures had stretched bits of the cover deep into the book, and the pages, less flexible than leather, had ripped and compressed, distorting the text and the woodcuts as much as a quarter inch around the one-inch hole. The hole, at least for Lynus, was just as fascinating a study as the material it distorted. And so, instead of reading around the tooth marks, Lynus found himself reading the marks themselves, pondering the bite pressure, tooth size, and salivary chemistry of Viktor Pendrake’s now-departed pet.

“Distracted again?” came a voice just behind Lynus.

“Edrea!” Lynus said. “I didn’t hear you sneak up on me.” He turned to face her, still clutching the argus-mauled tome.

Edrea Lloryrr held up a specimen jar with a single maggot writhing across its bottom. With her other hand, she swept a strand of hair back behind a pointed ear.

“You’d been gone so long I thought you might have forgotten what the specimen looked like.” His cheeks grew warm as she arched an eyebrow at him. “And I wasn’t sneaking, Lynus.”

“An Iosan spell, then. You have an unfair advantage.”

“I walk softly, and you weren’t paying attention.”

He opened his mouth to protest, but in truth he hadn’t been paying attention, and that was an unhealthy habit for any of Pendrake’s students. The professor’s field studies sent them traipsing through some of the darkest, most dangerous wilds in western Immoren. Some students came home with scars. Some came home maimed. Some didn’t come home at all.

“It’s a ringback, second-instar larva, maybe a day from molting,” he said, looking down at the book. He shrugged. “I guess I knew that before I even opened the book. I wanted to see how the woodcut compared to the specimen.”

“And?”

Lynus blushed again, his ears hot. Edrea was inviting him to expound, to talk to her.

With

her. Even after his clumsy comment about the magic he was still half-convinced she was using. He drew a deep breath.

“Burrick was a fine artist, but ham-handed with tweezers and pins. The woodcut shows distortions along the ventral axis.” He held the page so Edrea could compare it to the worm in the jar. “He drew this one after mounting it. Pulled a bit too hard to get it over the pin.”

Edrea smiled and nodded, but Lynus worried she was patronizing him. She was a decade his senior and had known the professor twice as long as he had. He was convinced that if she’d actually enrolled in the university, she’d be the professor’s senior assistant rather than him. How did she feel about that? Did Iosans feel jealousy the same way people did? Was there a spell for that? Why hadn’t she ever enrolled? Why was she looking at him with that one lifted eyebrow as if—

Lynus realized he was staring.

“I’m sorry,” he said, breaking off his gaze. “We’re supposed to be testing a theory, not critiquing illustrations.” He replaced the book on the shelf, then stepped around Edrea into the examination room.

Three large bottles of rotting meat stood on a stained metal table. Edrea had brought them in an hour ago, after aging them on the porch for weeks and not letting Lynus know which one was which.

“The ringback came from sample two,” he said, “which also had eggs and adults, meaning the flesh’s first exposure to the air was eighteen days ago.”

Edrea looked to the jars on the table, her expression flat.

Lynus held up a finger. “Wait! I almost forgot!” He grabbed a notebook from the stand next to the table and flipped through it. “Four days ago we had our first cold snap. That slows these fellows down a lot.” He rubbed his nose. “Fourteen days. Fifteen at the outside. Hmmm . . .” He scratched his head. “So close to third-instar. Fourteen and a half.”

Edrea’s eyes widened. “Congratulations. Fourteen days and,” she drew a watch from her pocket and nodded, “nine hours.”

Lynus felt himself grinning like a fool. A fool who, given a record of the weather and a list of the species of carrion bug common to the area, might tell you how long something had lain dead.

“I told you he could do it!” Viktor Pendrake strode around the corner. “Sorry to eavesdrop. I didn’t want to spook you.”

“Err . . . thank you?” Lynus said.

“No, Lynus, thank

you

.” Pendrake waved at the potted meat with a broad smile. “Put into wide practice, this could revolutionize not just our own field of study, but a score of others. Why, Whittaker’s course The Analysis Forensic, the one so popular with the more ambitious among the city watch, must be rewritten from bottom to top to allow for this entomological trick of yours, this method whereby one might examine the wriggling larvae in a dead man’s body and announce with certainty when the man became a corpse!”

Lynus shuddered at the thought of an enraged Professor Whittaker.

Pendrake pulled his glasses to the end of his nose and glowered over them. “Of course, you will need to write your own book, instead of reading all of everyone else’s.”

The professor chuckled, and Lynus relaxed. Entomological forensics might make a suitable second thesis, but Pendrake’s good mood suggested he had something more immediately adventurous in mind.

“Professor,” Edrea said with a short bow, “I thought you were meeting with the chancellor of archeology this hour.”

“I was interrupted.” Pendrake turned toward the entry. “Horgash! Stop poking the dracodile bones and come meet the lad who wired them together!”

Heavy steps sounded from around the corner, and Lynus realized he really hadn’t been paying attention—not if Pendrake and whoever owned those feet could have entered the lab without his noticing.

A seven-foot wall of bright colors and blue-grey skin turned the corner. The trollkin was a full head taller than Viktor Pendrake and half again as broad. He wore what had to be eight yards’ worth of tartan-patterned cloth draped over one shoulder as a sash, wrapped about his impressive girth, and hanging like a tabard.

His jaw was huge, like that of most trollkin, and a thick stripe of long, reddish quills ran from his forehead back to the base of his skull. He was older than most of the trollkin Lynus had met, if the heavy studding of craggy growths on that jaw was any indication. A pair of swords in two battered scabbards hung from a belt at his waist, one at each side. Palm-sized, rune-marked stone talismans hung from the cloth, the belt, and a chain around Horgash’s neck.

Judging from the numerous talismans, the swords, and his age, Lynus thought, this trollkin ranked highly in their society. Perhaps he was one of their champions, or one of the fabled sons of Bragg, whose shouted songs could bolster a line or rend flesh.

Lynus thrust out his right hand. “Lynus Wesselbaum, senior assistant to Professor Pendrake.”

“Horgash Bloodthroat,” the trollkin said, his right hand engulfing Lynus’. His voice sounded like someone sawing apart a kettledrum. Not of Bragg’s blood, then. With that wreck of a voice, he barely sounded like a trollkin.

Horgash scratched his craggy chin. “Pendrake may have mentioned you the last time our paths crossed. You’re the one who got carried off by vektiss, yes?”

“Err, yes,” Lynus said. He knew Pendrake liked telling that story. Apparently he told it even when Lynus wasn’t around. “That was me.”

“Edrea Lloryrr.” Edrea interrupted Lynus’ embarrassment with a nod and a bow. She too offered a hand, which Lynus thought might vanish completely in Horgash’s grasp. The trollkin accepted her hand lightly, and Edrea looked completely at ease, her tiny, beautiful hand resting on the monstrous knuckle.

“A pleasure,” he rasped. “Pendrake definitely mentioned you. Immoren is richer for you remaining uneaten by my distant dire cousins.”

Lynus knew that story well. The tale had been enlarged, it seemed, by Pendrake’s retelling. There had been only one dire troll that day.

Pendrake reached up and clapped Horgash on the shoulder. “Well, then.” He turned to Edrea and Lynus. “Grab a notebook, Lynus. Horgash tells me he may have found something new.”

They adjourned to a small study. Lynus took notes as Horgash spoke.

“I’m a trader these days,” he began with a glance at Pendrake. “Northeastern Cygnar and Llael—or what used to be Llael—from Merywyn in the north down through the trollkin villages in the Thornwood, then along the edge of the Widower’s Wood to Corvis.

“The roads have gotten rougher since the Khadorans took Llael. Rougher still this summer. There’s rumor of skorne armies in the east, and Leto has asked the kriels to arm themselves and interpose. Anyway, I’m the only outsider some of those villages see for weeks at a time.

“Something smashed the little village of Bednar no more than half a day before I got there. And I mean

smashed

. Not one log left atop another. I took a look around, but whatever did it was gone. Nobody left to talk to, either. I found only six bodies. All crushed, but not quite cold.”

Lynus looked up from his shorthand. “What about tracks?”

“Getting to it,” Horgash said. “There were a few footprints, but they looked like the villagers’. I expected big tracks, maybe for one of those skorne beasts, or a dracodile, or even a warjack. The ground had been pushed around a lot, but I couldn’t find tracks. And then I heard a distant rumble, like thunder. With the clear sky, I thought maybe what had done this wasn’t all that far off. So I saddled back up and rode hard for Corvis.”

Pendrake was squinting at a map in front of him. “Bednar . . . just off the lower Northern Tradeway heading into the Widower’s Wood?”

“The same.”

“It’s only a two-day march.”

“Professor,” Lynus said, “they were Cygnaran subjects. Shouldn’t we alert the city garrison?”

“I did that already,” growled Horgash. “I spoke to a lieutenant. He took some notes and sent me on my way. I got the impression those notes weren’t going to go very far.”

“I can speak to Colonel Bradley, but he’ll be slow to dispatch troops unless there’s smoke on the horizon or orders from Caspia,” Pendrake said.

Horgash grunted.

Pendrake turned to placate the trollkin. “There’s a war on, old friend.”

“More than one, I’d say.”

“A point I cannot argue.” Pendrake looked back down at the map. “I’m sure the colonel will dispatch somebody eventually. And I’ll send word. My concern is that by the time Cygnaran scouts have a close look at Bednar, the trail will have gone cold.”

Lynus looked at Bednar on the map. It merited only the tiniest of dots, almost swallowed up in the line demarcating the Widower’s Wood. Yes, there were soldiers and warjacks about, but this looked more monstrous in nature.

“It’s up to us, then,” he said.

“Indeed,” said Pendrake. “I’ll notify the garrison of our plans. Edrea, have the stable master ready our mounts.”

“Aeshnyrr will be happy for the open road again,” she said.

“As will Codex,” Pendrake said. “Not to mention me.” He pulled some scrip from his table and handed it to Lynus. “Now, off to Corcoran’s with you. We need provender for three normal appetites and one trollkin. The trail cools with every passing hour. Don’t dilly-dally, and don’t let Corcoran foist any bulging tins on you this time.”