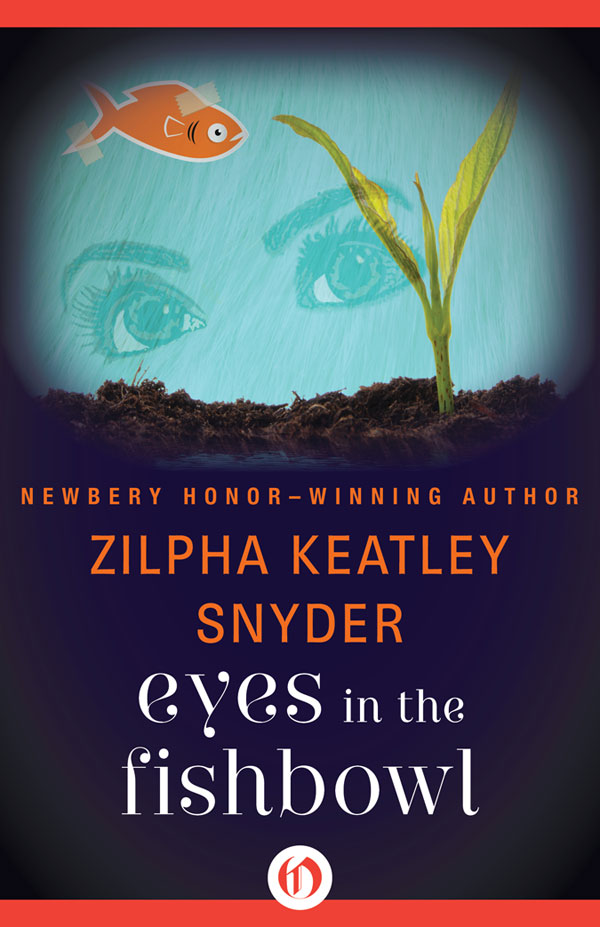

Eyes in the Fishbowl

Read Eyes in the Fishbowl Online

Authors: Zilpha Keatley Snyder

Zilpha Keatley Snyder

To Mother and Mom, with love

A Biography of Zilpha Keatley Snyder

L

AST NIGHT I

got the idea to put the whole thing into a song. I’ve been writing songs again lately, but this wasn’t like the others. What I had in mind was a kind of ballad, a song story like the ancient troubadours used to make up about an important event so it would never be forgotten. I wrote the chorus first and it went like this—

The Fishbowl Song

by Dion James

Nobody’s shopping at Alcott-Simpson’s

The very best store in town.

Nobody’s dropping by Alcott-Simpson’s

Since the rumors started going around.

Strange things have been heard there,

And stranger things are seen,

And a customer fainted dead away—

In the French Room

On the Mezzanine.

I did that much in about fifteen minutes and it, like they say, almost wrote itself. I worked out a melody and some chords and it sounded so good that I would have called up Jerry or Brett to tell them about it right then except it was pretty late already, and a school day today.

So instead I started in on the first verse, but that’s where I bogged down. It was hard to know where to start—what to put in and what to leave out. Obviously you couldn’t put the whole thing into two or three verses. I started going over it, trying to get some ideas—and the first thing I knew I’d gone back to the very beginning.

The real beginning—at least for the store and the people in it—must have been a little less than a year ago, around the time I first saw Sara. But for me the beginning went back to a long time before that. In a way, my part in the whole thing started about six years ago on the day I first discovered Alcott-Simpson’s. I was eight or nine years old at the time, and had just started to shine shoes on the corner of Palm and Eighth Avenue. Of course, it was only natural that it made a big impression on me when I first saw it. When I was eight years old—for various reasons having to do with my health and family situation—I’d hardly ever been outside my own neighborhood. Up until the day when José, who runs the flower stand on the corner of Palm and Eighth, found me being chased up an alley by some other shoeshine boys whose territory I’d wandered into, I’d never really been uptown; and my idea of a department store was Barney’s Bargain Center two blocks from our house. But then José said I could set up shop right outside his flower stand where he could look out for me, so I went with him to Palm and Eighth and there it was—a whole block of marble pillars, crystal chandeliers and gilded wood. I mean, it was like I was Aladdin and the genii had just plopped me down in the middle of an enchanted palace.

I was only in the store a few minutes that first time, but I can still remember how it was. For one thing, it was right then, that first time, that I got that feeling of walking into a separate world. After the ordinary winter world outside, dirty gray with a cold wet wind, inside Alcott-Simpson’s was like being on a different planet. The warmth was clean and smooth and loaded with something that was too high class to be called a smell. As a matter of fact, I was still standing just inside the door trying to sort out the smell—I’d gotten about as far as new cloth and leather and perfume and dollar bills—when somebody came along and invited me out. From then on, I was always prowling around Alcott-Simpson’s—and being invited out from time to time.

My main enemy was Mr. Priestly, who was in charge of the store detectives. It’s easy to see why he didn’t appreciate me hanging around Alcott-Simpson’s looking the way I used to until a couple of years ago. If you can picture a bundle from the Good-Will’s trash bin, with a mop of curly hair, a bad limp and dragging a big shoeshine kit, you’ll know what I must have looked like. It couldn’t have been good for the Alcott-Simpson image. But even after I changed a lot, and started dressing better, Priestly and his henchmen didn’t much like having me around, because by then they were convinced that I was a shoplifter.

They were dead wrong about that, because I never took anything from Alcott-Simpson’s that I didn’t pay for. I’m not sure why exactly. It was no big moral thing with me, and I certainly had chances. Maybe it was just that I’ve never liked taking risks—or maybe it had something to do with the way I felt about the store. It would almost have been like stealing from myself. Anyway, I didn’t. But Priestly was hard to convince, and two or three times he had me taken upstairs and searched. He always seemed puzzled when he didn’t find anything on me, and he probably thought I’d very cleverly gotten rid of the loot somehow. I guess he just couldn’t figure out why else a kid like me would hang around a big department store so much. I had my reasons, but I couldn’t have explained them, even if I’d wanted to.

Of course, one reason was probably just that it was so handy. For a few years I shined shoes right outside the big glass and bronze doors of the east entrance, and from time to time I’d just stroll in—to get warm in bad weather, to see what was new, or just to catch up on the latest store gossip with a few friends I’d made among the clerks. Then when I began to outgrow the shoeshine business a couple of years ago, most of the new jobs I found were pretty much in the same area. Usually in the city a guy is pretty much out of luck from the time he outgrows the shoeshine and paperboy businesses, until he’s sixteen and can be put on a payroll. But I’d made a lot of contacts while I was shining shoes, and I managed to do all right. Most of my jobs were pickup things that I’d developed into a regular schedule. I ran errands, washed display cases, cleaned up and did occasional stock room jobs—mostly in the smaller shops on Palm Street. Also, I still kept my shoeshine stuff at the flower stand, and even though I didn’t shine shoes on the Street anymore, I kept a few old well-paying customers who liked to have me come up to their offices to give them a shine. That whole area, around Eighth and Palm was kind of my territory and Alcott-Simpson’s was right in the middle of it—in a lot of ways. I guess that’s why, when all the trouble started at the store, I was right in the middle of that, too.

I think the trouble probably started early in January, and it was around the middle of the month that I first saw Sara. Before that time I

had

heard a rumor or two, but nothing definite; and I don’t think the rumors were on my mind at all on that particular afternoon. If I had any special reason for walking through Alcott-Simpson’s that day, it must have been partly that I wanted to see what the decorating theme was for the after Christmas sales. Alcott-Simpson’s was practically famous for its display themes. But mostly I just wanted to get in out of the cold for a minute. Outside it was doing the Winter-Wonderland bit for real, and my jacket wasn’t exactly mink, if you know what I mean.

The first thing I did was to drift over to a bench I knew about near the east entrance and sit down. The bench was in a little alcove behind Ladies Gloves where customers were supposed to get out of raincoats and boots and stuff in bad weather. Mrs. Bell, who worked in Ladies Gloves, knew me. She was a typical Alcott-Simpson clerk, a shell of perfect dignity hiding a heart of pure nothing, but she was friendly enough to warn me if Priestly or one of his boys were heading my way; so I used the bench behind Ladies Gloves quite a bit. Quite a few times I’d even curled up there and gone to sleep—when I’d been particularly tired and cold. But it was late that day and I only meant to stay there until I got warm and then go on home. I’d only been sitting there for about a minute though when I began to notice something.

I don’t know exactly what it was I noticed. I don’t remember seeing anything the least bit unusual. I didn’t hear anything either, at least nothing definite—but maybe it did have something to do with hearing. It was as if the low hum of movement and conversation that you can always hear in a big place like that was on a different key, higher and faster, like the tuning was a little bit off. I was beginning to get the feeling that something was up, so instead of going on home I dropped in behind two fat ladies with a lot of packages and strolled down the aisle towards Cosmetics. I had a good friend in Cosmetics.

Madame Stregovitch lived near us in the Cathedral Street district, and she had worked at Alcott-Simpson’s for years and years. I don’t know why everybody called her Madame instead of Mrs., except that you just couldn’t imagine calling her anything else. It went with her accent, and her personality, which was very positive. She’d been at Alcott-Simpson’s so long that a lot of the important customers were convinced they couldn’t get along without her, and for that reason she could do just about as she pleased. But she was the only one. Most of the clerks at Alcott-Simpson’s wouldn’t have sneezed without asking permission.

It’s a funny thing, but when I first started hanging around, I used to think the Alcott clerks were something special. The way they dressed and acted, you got the feeling that they were all a bunch of eccentric aristocrats who were just working for the fun of it. You had to be around for a long time to find out what most of them were really like. Basically, most of them were a scared bunch of underpaid apple-polishers, who put up with all sorts of bullying just so they could go on associating with all that mink and money. At least, I guess that’s the reason they did it. You’d have to have some sort of hang-up to make you go on putting up with a lot of those A-S big shots and all the rules and regulations, the way the clerks at Alcott’s did.

All except Madame Stregovitch. If there was any bullying going on around her, she was right in there doing her share of it. She even ordered her Rolls-Royce-type customers around, and nobody ever complained. They wouldn’t dare. She affected everybody that way. It was just something about her that you couldn’t exactly put your finger on.

When I got to Cosmetics that day, Madame was busy with a customer; but she saw me and arched an eyebrow in my direction. Madame’s face was dark and sharp and full of bony edges. She almost never smiled, and her mouth hardly seemed to move even when she talked; but her eyes and eyebrows had a large vocabulary all by themselves. Right at the moment she was busy rubbing a drop of something on the cheek of a great big woman with a long nose, saggy eyes and a short brown fur—probably a beaver. (The coat I mean, anyone who hangs around Alcott-Simpson’s can’t help getting to know a lot about furs.)

“You see, my dear,” Madame was saying in the soothing hum that she always used on customers, “how it brings out your delicate coloring.” Madame doesn’t have much of a foreign accent, but she clips off her words and arranges them a little differently than most people.

In a few minutes the big woman went away with a dazed smile and a whole box of make-up stuff, and Madame came over to where I was waiting.

“Dion,” she said, “I have missed you. You have not been to see me since Christmas. You have not been sick?”

“No,” I said. “I’ve been around. I just haven’t been coming in much. Not enough business the first of January. Nobody to hide behind when old Priestly makes his rounds.”

“Mr. Priestly, pah!” Madame Stregovitch said, shrugging her shoulders and tilting her eyebrows to a disgusted angle. “He has greater things to worry about these days than one harmless boy. You must come and see me, as always. In the midst of so much falseness, one’s eyes are gladdened by the sight of such glorious youth.”

Actually, Madame Stregovitch wasn’t as weird as she sounded sometimes. It’s just that she got started raving about how good-looking I was, way back when I first used to visit her, when I was a skinny little crippled kid. Of course, I really knew, even then, that she was only trying to make me feel good, but I got a kick out of it anyway. Eventually it was just a routine we went through.